Indigenous Australians have occupied the Atherton Tablelands for tens of thousands of years. While the oldest human occupation site found in the region is Walkunder Arch Cave at Chillagoe, which dates to 18,000 years,1 pollen analysis shows that the frequency of fires beginning around 45,000 years ago is indicative of human occupation.

At the time of European arrival, the eastern, rainforest-covered part of the tableland was the home of the Djirrbal and Ngadjonji tribes who were part of the Djirrbalngan language group. The drier, more open forests to the west were peopled by the Jidabal and Barbarum, while the northern end around Kuranda was the domain of the Yidinji.

There were elements of aboriginal culture on the Atherton Tablelands that differed from other areas of Australia. As around Cairns and the coastal region, it was observed by J.V. Mulligan, and others, that some of the aboriginal camps were 'semi-permanent,' and resembled townships. Cleared areas and walking tracks were maintained, and the people were not strictly nomadic.

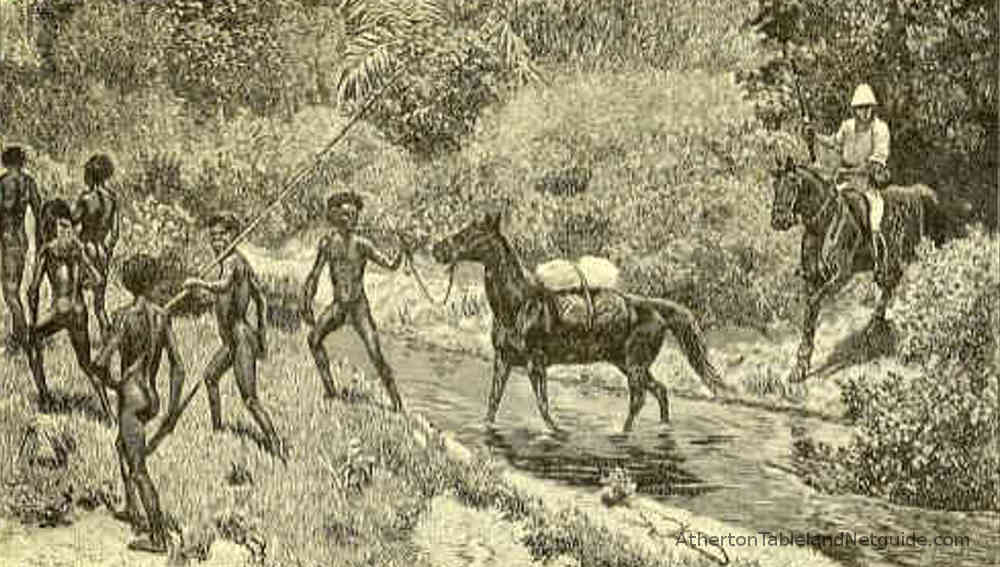

The coming of white settlers caused great disruption to the aboriginal traditional way of life. There was frontier warfare, dislocation, starvation, and instances of wholesale massacres of groups of blacks. It is estimated that the population of aborigines in the Cairns-Tableland region was reduced to less than 20% of the original number in just 20 years.

After the period of frontier warfare, surviving aborigines were subject to the protectionist policies of the government. Aborigines were removed from their traditional lands and placed on government reservations or church missions.

J.V. Mulligan and his party were the first Europeans to walk on the tablelands on his expedition of April 1875. The Mulligan Expidition met the Barron River at Bibhoora, and followed it south until they reached the jungle. Skirting the jungle, they followed native tracks through the country around the present day Atherton, then ascended the range to find the Wild River (as Mulligan named it), and found rich deposits of alluvial tin.

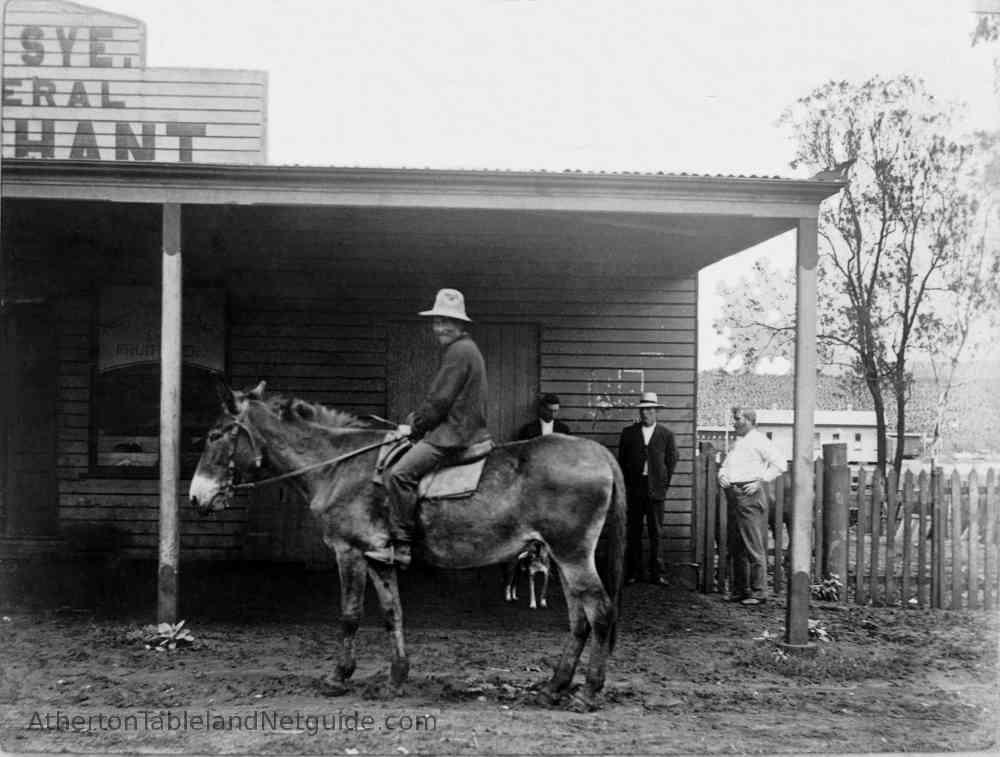

A legendary figure in North Queensland is the explorer Christie Palmerston, who was employed by the various local government bodies of the coastal ports to find tracks to the mining fields as Cairns, Port Douglas, and Geraldton ( now named Innisfail), as the three port settlements competed to be the dominant port, and road and rail terminus for the resource-rich hinterland.

Scientists were drawn to a region where new species of plants and animals could be discovered, named, shot, and bagged for museums in the 'old world.' In 1880, Carl Lumholtz traveled from Norway on such an expedition, and spent four years in Australia, which included 10 months in north Queensland on the Herbert River.

During his time in north Queensland, Lumholtz traveled and lived with aborigines who still lived a traditional way of life, with little-to-no contact with white society. Hearing reports of a mysterious creature in the form of a kangaroo that could climb trees, Lumholtz explored the southern part of the tablelands until he found the tree kangaroo - Dendrolagus Lumholtzi. Lumholtz recorded his experiences, and in 1889 published Among Cannibals; an account of four years' travels in Australia and of camp life with the aborigines of Queensland.

John Atherton was the first European settler on the Atherton Tablelands. From his cattle station near Rockhampton, he drove a large herd of cattle north to the Palmer River goldfields to sell to the hungry miners in 1873. Having found it a lucrative expedition, he repeated the feat again in 1875, this time to the Hodgkinson goldfield.

1875 was also the year Mulligan had explored the tablelands. Based on his reports, in 1876 Atherton retraced Mulligans track and claimed land near the present day town of Mareeba. He moved his family and cattle there in 1877, establishing his station, which he named Emerald End.

Atherton discovered alluvial tin at a place he named Tinaroo, and this brought the first miners to the tablelands. He also led Willie Jack and John Newell to the Wild River, where Mulligan had reported the presence of alluvial tin. This led to the foundation of Herberton, in 1880, the first town established on the tablelands of north Queensland.

Tin mining became the backbone of a nascent regional economy, giving impetus to the timber and agricultural industries by creating a local demand, and an infrastructure for transport, communications, and trade. A track was made connecting Port Douglas and Herberton, and eventually a railway connected Herberton with Cairns. Prospectors exploring the country west of Herberton found the mountains rich with outcrops of tin and other base metals. Other townships sprung up, although most were short-lived. Along with tin, there were mines exploiting silver and silver-lead, wolfram, and copper.

The mining industry in the "wild hills" from Herberton west to Chillagoe created a demand for timber for both construction and fuel. The rainforests provided millable timber for local use, and high-value timbers such as red cedar which could be sent to more distant markets. The township of Atherton began as 'Cedar Camp', and after the valuable timbers were removed, the fertile soils provided the base for the agricultural industries that continue to support the regional economy today.

In May, 1905, Digby Denham, the Queensland Minister for Agriculture (and Premier from 1911 to 1915), toured the Atherton Tablelands.

A visit was made to the Hou Wang Temple in Atherton's China town, which was described as 'the finest (Joss House) in the colony.' That night at the Atherton Hotel, Denham made a speech in which he said 'the Chinamen were largely the pioneers of the district, and made farming possible on the Johnstone. They fell nearly every acre of the scrub."2

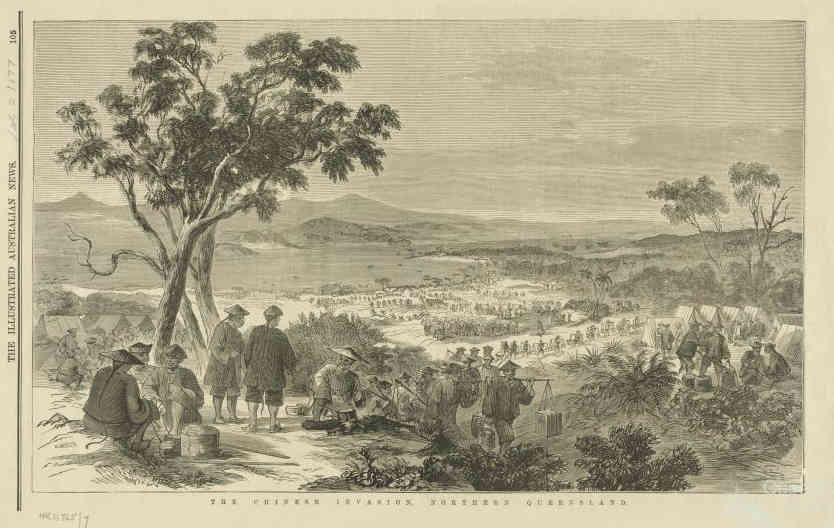

It is estimated that more than 100,000 Chinese entered the Australian colonies between the 1840s and 1890s. The Palmer River gold rush beginning in 1873 saw an influx of Chinese gold seekers, and by 1877 there were around 17,000 Chinese in North Queensland.

While many Chinese returned to China after the gold rushes, others chose to stay despite racist attitudes and government policies which attempted to deter their acquisition of land and access to resources. To this day, Europeans are fondly referred to as the first settlers, and pioneers, but other races rarely so. In the days of early settlement of the north, South Sea Islanders, Malays, Chinese, Japanese, and other Asia-Pacific peoples were considered only in their usefulness to the white race, especially in the tropical northern regions of Australia.

In North Queensland, Chinese formed partnerships to lease land from European settlers, and a system evolved where white settlers acquired grants of undeveloped land which they leased to Chinese who did the hard work of clearing and cultivation. They grew crops of bananas, sugar cane, maize, and rice, and introduced fruits particularly suitable to the tropical region whose names have been anglicized from Chinese, including mango, litchee, longan, and durian. By 1911 the population of Chinese in the whole of Queensland had fallen to 5,518, however, in Atherton in the following year, the population of Chinese had risen to over 1,000, almost one-fifth of the state's total. A Chinatown existed well separated from the European part of town. As in other areas, the Chinese farmed under lease arrangements. Soldier Settlement schemes enacted after the First World War, saw the end of this system and the demise of Atherton's Chinatown. Today all that is left of Atherton's Chinatown is the Hou Wang Temple.

For a great insight into the life of a Chinese immigrant who arrived in north Queensland chasing riches on the Palmer River, and who stayed and made a successful life and career, read Tom See Poy: My Life and Work.

The Atherton Tablelands served as an important supply and support base for operations in the South-West Pacific during the second world war and under 'Project Atherton,' became the largest military base in Australia.

Project Atherton was a training base where troops could acclimatise to the tropical conditions and train in jungle warfare. With 164 war graves, the Atherton War Cemetery is the third largest in Australia.

Rocky Creek became the site of the 5th Australian Camp Hospital and 2/2nd and 2/6th Army General Hospitals. It grew into a 1,200 bed hospital serving wounded soldiers as well as those suffering from tropical diseases. In its three years of operation it treated 60,000 patients. Today it is the site of a war memorial park, and is a popular campsite.

The arrival of the military was important to the further development of the tablelands. Valuable infrastructure was built, including the construction of the Kuranda Range Road, which was just a rough track before the war, and had seen little-to-no improvement since it was used a dray road in the late 19th century.

Along with the hospital complex at Rocky Creek, construction work beginning in 1943 saw the building of tent camps, huts, stores, bakeries, mess kitchens, entertainment halls, sewage plants, army farms, roads, bridges, and airfields. Some of the military-built 'igloo buildings' were converted to civilian use after the war and can still be seen around the tablelands, including 'Merriland Hall' in Atherton.

United States Army Airforce units were based at Mareeba from mid-1942, along with a US hospital and US Anti-Aircraft units. Mareeba became the advance operational base for bombing missions in the South-West Pacific Area (SWPA). Mareeba airfield was constructed to accommodate B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. Seven US heavy bomber squadrons flew missions against targets throughout the South West Pacific Area. The Americans named it Hoevet Field.

With around 40,000 troops regularly stationed on the tablelands, and the number sometimes swelling to around 100,000, demand for fresh milk stimulated the local dairy industry, and caused the Malanda dairy factory to switch from cream-based to milk-based production. After the war, Malanda milk continued with the distinction of 'the longest milk run in the world', transporting milk as far west as the Northern Territory, and as far north as New Guinea.

Although the period of the Atherton Project lasted only two years from 1943 to 1945, it changed the landscape and economy of the tablelands, and its effects can still be seen today.

In the 1950s Tinaroo Dam was constructed on the Barron River as part of the development of an irrigation scheme to support agriculture around Mareeba and Dimbulah. The dam also allowed an increase in generating capacity for the Barron Gorge Hydroelectric Power Station.

The Mareeba-Dimbulah Irrigation Scheme helped increase agricultural production. Although at first it was mainly aimed at tobacco production, today it supports a diversity of crops which include mangoes, bananas, pawpaw (papaya), avocados, sugar cane, and coffee along 365 kilometers of irrigation channels.

The damming of the river created a lake which is 3,360 hectares in surface area, creating a popular fishing, boating, and aquatic recreation area. In 2004, a hydro-electricity generator was added.

During construction of the dam, a temporary town was built to house hundreds of workers. The town included shops, a police station, and a fire station.

Read more Far North Queensland History

If you enjoyed reading this page, please show your support and tip the author the price of a coffee or beer: