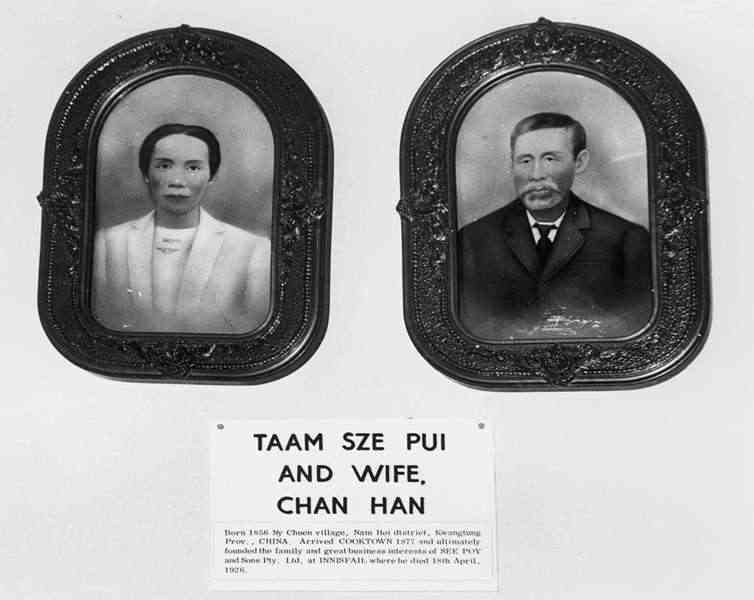

Portrait of Taam Sze-Pui (Tom See Poy). Library of Queensland, no date.

At the time of writing, this is the first hypertext (HTML) version of My Life and Work by Taam Sze-Pui. The book is available in digital form in various archives on the Internet including the The National Library of Australia in a photographic format.

My motivation for creating a web version is for personal reference as I continue to explore the history of Far North Queensland, and to share the valuable resource with others. The obvious benefits of a hypertext document include searchability, readability, and linkability.

Taam Sze-Pui was born in Guangdong Province, China in 1855 or 1856. At the age of 22, Taam, his father, and younger brother, fled a life of poverty and joined the gold rush to the Palmer River in Far North Queensland, Australia.

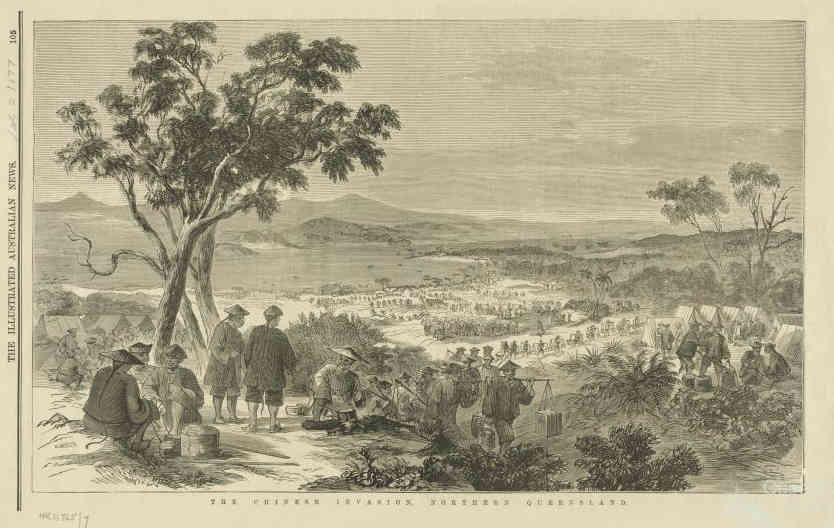

The Taams arrived at Cooktown in 1877. The Palmer River gold rush had been in full swing since 1873, and the population on the goldfield had risen from 2,000 in 1874 to 19,500 in 1877. More than 90% of these people were Chinese.

Taam adopted the anglicized form of his name, and was known in Australia as Tom See Poy. However, as he chose Taam Sze-Pui on his autobiograhy, written just a few years before his death, I have chosen to refer to him as such.

Taam's autobiography provides us with rich insight into life on the gold fields of North Queensland in the early frontier era, and in the Cairns region as it became settled and developed in the late 19th and early 20th century. Failing to succeed in finding a windfall of gold, Taam's life is testament to the value of hard work, thrift, and perserverence.

Taam followed a familiar course with those of his countrymen who stayed in Queensland after the gold rushes, working as a labourer clearing land for cultivation around Cairns and the Johnstone river. Those who benefited the most from his labour were the European settlers who became farmers on that land. However, Taam was able to live frugally, and save enough of his small wages to eventually set up a store in partnership with some fellow Chinese. Eventually, he bought his partners out, and built up an enterprise knowns as See Poy & Sons.

One of the unique aspects of Taam's story is the Chinese perspective. The Chinese played an important role in the development of Far North Queensland, but while they are often written about in the historical records, Chinese voices are rarely heard from a first-hand perspective.

I have made only minor edits to the original text, correcting the spelling of one placename mentioned several times, catching one or two errors missed by the book publisher, and adding some paragraph breaks to improve the readability of longer passages. I hope over time to add some pictures and annotations.

Phillip Charlier, Taipei, Taiwan, August 26, 2023 (Late summer of the 112th year of the Republic of China.)It was spring when, in my travel, I arrived at Innisfail, Queensland. I was a guest of my father’s friend, Mr. Taam Sz Pui of the Tung Woh Store. Mr. Taam was kind enough to show me the manuscript of his autobiography and instructed me to write a short introduction. Alas, I am no scholar and therefore, not equal to the task!

Nevertheless, as it is not courteous to disobey a command of an elder, I do what I can so as to discharge my duty.

As I finish reading this manuscript of Mr. Taam, I realize that his clear perception of truth and firmness of mind surpass all others. By my observation, he has three outstanding qualities which are beyond our reach.

First of all, from youth to manhood and thence to old age, he endured hardship for fifty years as if it were one day. Never did he look tired nor wasted his labor.

Secondly, he contents himself with simplicity and holds himself steadfastly to honesty. Kindness is what he loves to dispense and righteousness is what he lives for.

Thirdly, he is very agreeable to be associated with. Neither cross words nor angry looks has he ever employed towards his fellow men. He is wealthy but not proud. With these fine qualities, I have no wonder that his family has become prosperous.

Finally, in committing this to writing his experiences for his descendants, he has made a model of himself. The words which he used to express the deepest meaning of life are simple and clear. The rules of business are indeed sound and pacticable. This is exactly what virtuous man in the past called “Life as a teacher.”

Chan Wen Lung, In the middle of spring of the fourteenth year of the Chinese Republic.It is indeed hard to found an estate yet it is by no means easy to maintain it.”

This is well said by one of our sages. However, if one has not actually gone through the hardship of life, he can hardly realize what it really means. I am getting old and cannot do much. Nevertheless I have not forgotten my life experience and still can relate to you the hardship endured in founding my family estate.

I was born in a poor family. As I reached the age of seven, my mother died leaving my elder sister who is one year older than I and my younger brother just learning to walk. I went to school at eight and had to abandon my studies at eleven. It was not because I disliked to study but we were poor.

For generations, farming had been the chief occupation of our family. My grandfather was old. Without a mother, I was left in great loneliness. When our aunt came to pay us visits, the situation grieved her and moved her to tears. Being so, my grandfather asked her to bring me up. Consequently I depended on her for support.

My uncle was a small merchant and ran a little shop in the village, where I worked for him, obeying all his instructions and commands and never dared to complain about hardship. After three years, my aunt said I was quite teachable. Until one day, a man came in to buy sugar and while I was getting it for him from the jar, the latter slipped from my hands and was broken to pieces. My uncle, without consideration, showered angry words. For fear of punishment, I escaped and went home. The whole case was presented to my grandfather who, fortunately, did not blame me.

From then on, I helped my father on the farm in raising fish and planting mulberries. At dawn we began to labour and at dark, we stopped. Life was calm and very pleasant.

My grandfather passed away while I was seventeen. Four years later, there occurred in the village a terrible flood which swept away all our fish and mulberry trees. This calamity left us in further reduced circumstances.

There was a rumour then that gold had been discovered in a place called Cooktown and the source of which was inexhaustible and free to all. Without verifying the truth, my father planned to go with his two sons. We started from our village on January the 18th, 1877. On January 22nd we sailed from Hong Kong and reached our destination on February 10th of the same year.

Oh what a disappointment when we learnt that the rumour was unfounded and we were mislead! Not only was gold difficult to find the climate was not suitable and was the cause of frequent attacks of illness. As we went about, there met our gaze the impoverished condition and the starved looks of our fellow countrymen who were either penniless or ill, and there reached our ears endless sighs of sorrow. Those who arrived first not only expressed no regret for being late, on the contrary, they were thinking of departing. Could we, who had just arrived, remain untouched at these sad tales?

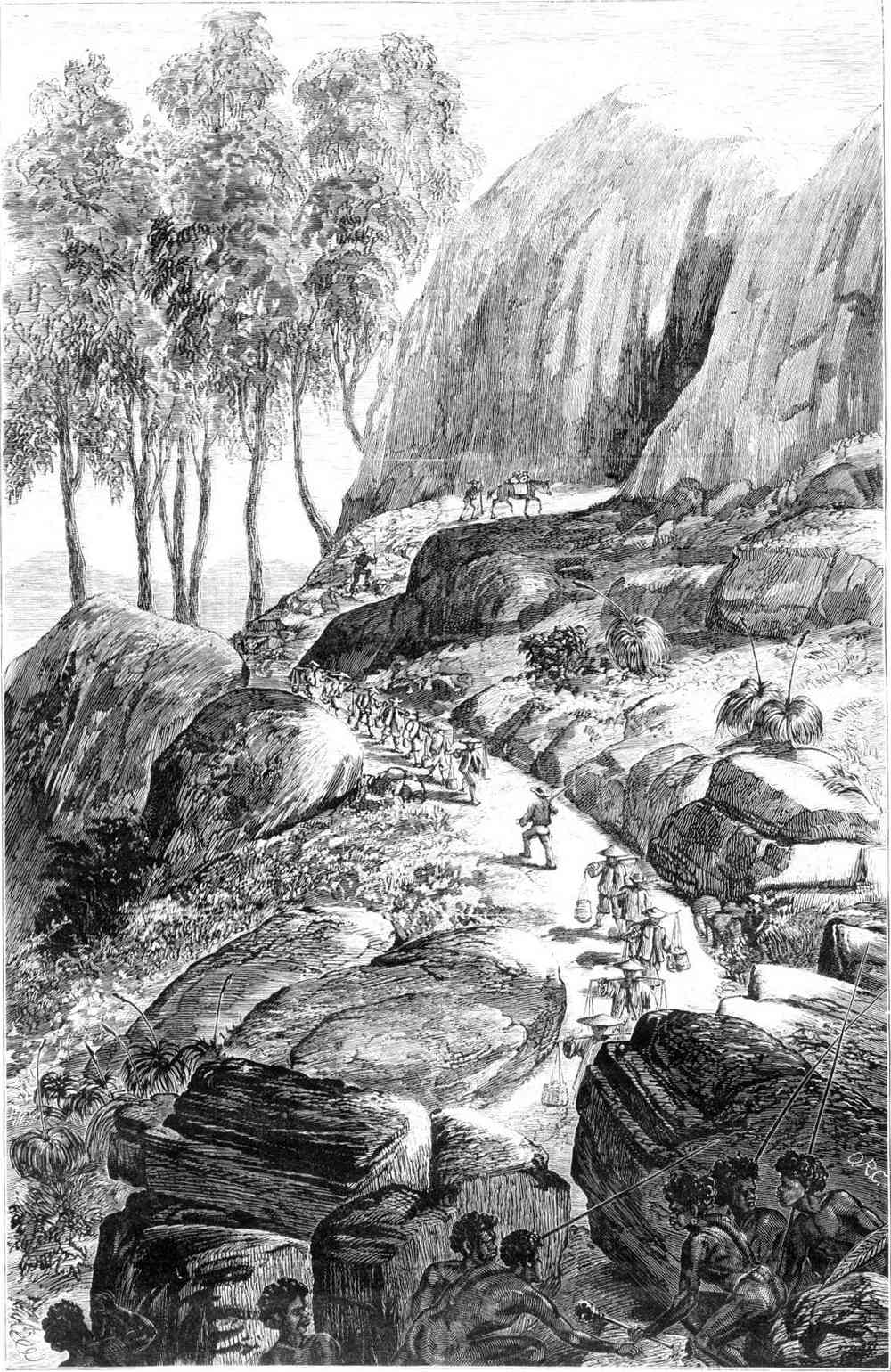

But since we had come, we might make an attempt. Therefore we bought hoes, shovels, provisions, utensils, etc. Carrying or balancing on the shoulders the supplies, we started a foot in a company in the direction of the mountain region on February the 16th, 1877. When we had accomplished sixteen miles, night came and we had to stop. Sleeping in the dew and exposed to the wind, the hardship is better imagined than described.

Early on the third morning, we resumed our journey. Walking sometimes slowly and sometimes briskly, we kept close to the group not daring to detach ourselves lest we should be set upon by the black natives and probably be devoured by them. The fear of such a fate kept one and all together and no one dared tarry behind to rest or to regain his breath. At the 20th mile, we came upon a stream. Here we put down our burdens, prepared to cook and each attended to his own work. Thus we rested for two days before starting again.

This time we had to climb stiff cliffs and scale over high precipice, which so exhausted us at the 26th mile that we could hardly move a step further. All wanted to rest and this we did for three days. Then we advanced as far as the 40th mile. At this point a torrential rain had caused the stream to rise and we had no boat to cross by. We could do nothing but sigh. Braving wind and rain, we patiently waited for the stream to dry. Our provisions had now been consumed. I was now forced to return to Cooktown for supplies. The journey was resumed as soon as the water began to subside.

It was about a month after we had started when we reached the 52nd mile where we rested. Here we came to a great plain as wide and open as a road.

Proceeding to the 72nd mile, we reached a place called “The Foot of the Great Mountain.” Behold, before us was a great mountain with the peak projecting high up into the clouds and whose height was beyond my calculation. We made our climb at a slow pace and zigzagged down on the other side. Inquiring of some companions I was told we had traveled eighty-two miles. Completely worn out and weary, some discarded part of their supplies to lighten the burden, and some were in tears.

Our limbs were numb; our shoulders were bruised and bleeding. When attempts were made to change our clothes, it was necessary to forcibly pull the clothes from the coagulated blood. The pain was unendurable.

“Alas to suffer this torture of the flesh for no wrong doing,” I sighed bitterly.

Tarrying for a few days, we advanced again. Very soon, we reached the 96th mile and stopped. Driven by hunger, we approached and English bakery there and begged for bread. Fortunately, the Englishman took pity on us and gave us some. Thus our hunger was appeased.

It took us fully three months to cover one hundred miles in our journey. We then began to sift sand but to our utter disappointment, there was no gold. Mr. Kwok Leung happened to pass our way and very kindly gave us instructions. We then obtained one or two candareens per day. This was just sufficient to pay our daily expenses.

Soon after, misfortune overtook me. My heel had and ulcer which made it painful to walk. Being informed this malady could be cured by pressing the sore over a large piece of heated stone which would cause the blood to circulate, I tried and found it successful. However, before I had completely recovered, some of my comrades moved camp. There was no alternative but to follow. At the hundred and twentieth mile, we decided to stop. Just then we heard that the gold strike was very rich about ten miles ahead. We immediately dashed on helter-skelter like fowls. When we covered one hundred thirty miles, it was already July.

Having staked our claim, we began panning and obtained daily about six or seven candareens. But then my father and brother, one after the other, fell ill and were confined to their beds groaning. This worried me terribly. Fortunately, Mr. Chan Poon passed by and told us that they had caught eruptive fever. By following his prescription they both recovered. We wished to express our gratitude but he courteously declined. A man of such great virtue could hardly be found anywhere now-a-days.

Not long after, news of the hardship and the stranding of the Chinese in Cooktown reached China. The relatives at home looked dismal and unhappy at the news of their sad plight. There were not a few destitutes who had traveling expenses sent from China before they could return. My second uncle, on hearing the information, mortgaged our family house for $160 Mex. And remitted the amount through Man Chuen, a pearl shop in Canton. We received it through Man Chuen On store in Cooktown. The sum realized was thirty-two pounds which was meant for the return expenses of my father, brother and myself. But fate was against us for my father again got ill. The whole amount was soon spent.

It was about December when we located ourselves one hundred and sixty miles and here remained stranded for a considerable number of years. I first thought of being a peddler, which idea my father favoured. But in this business a heavy load on the shoulder would restrict the territory one could cover; yet the lighter the load, the less the gain would be. Next my thought turned to domestic service, but the position was disrespectful and the wages poor. There was no work that seemed fit. Finally I was driven back to take up my former occupation of digging for gold.

One day I missed my footing and sprained an ankle. The pain was so acute that I could hardly move. In the mountain region, where could one call a doctor? Worse still, my father and brother were out at work in the gold field. With a terrible thirst to be quenched, I crawled about for water to make tea. As I came to a high place, I had to lift the disabled foot over with both hands. I exerted too much force and hit the foot against a boulder. By accident this made the dislocated joints come into place and I could then walk as usual. Thus grief was turned into joy.

One day we reached the Mitchell River which looked like a spanse of the ocean. Here we settled down for the night. About nine oclock that night we suddenly heard the hues and cries of the black natives. We aroused ourselves, set off a signal of alarm and kept watches throughout the night as if we were encountering a mighty enemy. When dawn came, we immediately moved away to avoid them.

Five years had passed, I now realized that to search for gold was like trying to catch the moon at the bottom of the sea. Forsaking it for something else, I worked in a restaurant at the wages of two pounds a month. At the end of the year I had already saved twenty-five pounds, sixteen shillings and six pence, after deducting expenses.

It was six years since we first came but we had accomplished nothing. Sending him my savings for expenses I beg my father in my letter to return home. He declined the suggestion for he wanted to buy the vegetable garden with a few pigs in it which Lo Sham Lee were offering for sale. He disregarded my entreaties and closed the transaction. There followed a drought; the vegetables withered and the pigs all died. My father gave up the whole venture and went again digging for gold. I was left to see the garden sold, but after having waited in vain for a year, my friend advised me to abandon it.

In March 1882, some Englishmen advertised for labourers to go to Johnstone River Valley to develop the barren land into a sugar plantation. Mr. Lum Leung and I immediately set out for Cooktown together and accepted the call. We reached Johnstone River on April the 5th. Such barrenness met our gaze that we felt we were dwelling in an age of universal wilderness. There were neither roads nor means of navigation or transportation. Before the manager arrived, we had to wait near the harbour. He arrived a little over a month later, and taught us how to use wood to make boats to navigate the harbour and get our provisions. We laboured to clear the thorns and cut the shrubs. At one time, while I was chopping a big tree, it suddenly fell on me. It was a miracle that some branches supported it well above the ground and thus I was saved from being crushed to death.

When the work was finished I accepted a job in Mourilyan Valley in September of the same year. After having saved by frugal living some wages, I again wrote to my father begging him to return to China sending him fifty-four pounds to defray expenses. He consented and took the first boat home. My younger brother had gone from Cooktown to Cairns and worked in a land-developing company. But he remained as poor as before.

Prospects began to brighten and soon the Englishman promoted me to be the foreman. Early one morning while riding to inspect my men, my horse, being wild and difficult to control, refused to go and then suddenly reared and threw me to the ground, when I applied my whip. I was rendered unconscious for some little time before I was able to get up and walk.

Up to the 9th year, my younger brother had no success. So I asked him to come to my place. When finally he came, he was interested in a banana plantation. Too eager to take time to find a good partner, he associated with a disreputable character, and the result was the loss of about sixty pounds.

By that time, my savings had increased. A peddler named Yuen Kiu was offering to dispose of his whole stock-in-trade because of reverses in gambling. I knew there was profit in it and went into partnership with Mr. Luk Fui to purchase the whole business. We sold the goods later at favourable prices, and each shared some profits. Henceforth my mind was set to become a merchant.

In July 1883, Luk Fui, Luk Tong, Lei Kam and myself entered into partnership and opened the Kam Woh Store in Mourilyan Valley. About October I received the sad news of the death of my father, and hurriedly sent money home for all funeral expenses.

The next year we found out that our partner, Lei Kam, had committed some selfish acts and there were concrete evidences. The case was brought before all the partners for decision as a result of which, he was asked to withdraw. Mr. Luk Leung was invited to become a partner and the name of the store was forthwith changed to Tung Woh, to show our dislike of the word Kam by eliminating it.

At the end of that year hearing that the black natives were coming to attack us, we moved in haste our store to the Johnstone River Valley. Three years later when the books were closed and the accounts balanced, the net worth of each partner amounted to eight hundred pounds. Messrs. Luk Leung, Luk Tong and Luk Fui, feeling satisfied and desirous to return home, were willing to dispose of their respective interest to me so that I became the sole proprietor.

Taking advantage of my partners return to China I sent a letter and some money home through them. It was then that I received the shocking news that my grandmother had died and my sister had become a widow and was left with small means. Immediately I wrote to my sister begging her to come home and assume the duty as head of the household, the expenditure of which I would remit home every year. I also arranged for my nephew Ah Chi to go abroad to earn his living.

After my partners departure, the burden of management devolved upon myself. Naturally I displayed a more energetic industriousness. The business remained normal during 1888 and 1889.

In 1890 a devastating flood laid waste the town; we had to shelter on the upper floor. Some of the goods which we could not remove in time were damaged by the water and later sold at a low price, resulting in a slight loss. The next year I contracted beri-beri. The disease reached knee high, when I journeyed to the next town to consult a doctor. Fortunately the prescription was effective and I soon recovered.

The inherent stupidity of my brother Yuen had always worried me. After his failure in the banana plantation partnership, I sent for him to assist me in the store. However, he possessed not a single ability. The fundamentals of arithmetic he knew not; English he could neither converse in nor understand. Some customers often took advantage of his inability and he made countless mistakes in his transactions. In 1892, I arranged for him to go home to get married, paying him one hundred and twenty pounds as wages to cover expenses. I also instructed him, in case of need, to apply to the Fook Wo Cheung Firm in Hong Kong. As I was an outside partner and the firm, being also my buying agent, would make advances of fund on my account.

From 1893 to 1896 I continuously received letters from relatives urging me to return to get married, saying To have amassed great wealth and not to return home is comparable to walking in magnificent clothes at night.” Some dwelt on the great responsibilities by quoting “There are three things which are unfilial, and to have no posterity is the greatest of them. They advised marriage was essential and not to overvalue gains and belittle separation. Their arguments were sound and persuasive. However, I thought to myself that, driven by poverty so far from home and having hitherto fought against the tide, the course now was to add sail to my boat and take advantage of the favourable wind. Such an opportunity should not be lightly disregarded. Furthermore, it was not very easy to earn a living in China. If I were to remain, it would not only benefit me alone, but also many others. On the other hand, to close up and return where could they go, when the younger generation, relatives and friends should desire to find an occupation. Satisfied, I continued to consider the seeking of profit as paramount and did not attach much importance to the question of marriage.

When my relatives realized my obstinacy, they planned with my sister to find me a mate. On January 14th 1897, they contracted my marriage with the daughter of the Chiu family and arranged for her to come. I was then forty-three years of age.

When my wife arrived, I taught her English which she readily understood. Shortly afterwards she was able to help me a good deal. The English ladies liked to deal with her. She took charge of the sale of ladies dresses and piece goods and managed them all neatly and orderly. She had no fear for hard work, consequently the business flourished.

In 1898 our first daughter, Mei Tim, was born. Two years later came Mei Kiu, our second daughter. In 1902 my wife gave birth to our first son, Wui Hing.

On February 11th, 1904 a flood swept the town but it did not do much damage. The next year she gave birth to the second son, Wui Wing. There was a great storm in the night of January 26th, 1906 and we suffered a small loss. On August the 16th, 1907 our third son, Wui wah, was born.

On January the 25th, 1908 my wife, anxious to see her relatives, made a trip to China and took with her the children that they could pay their respects to the ancestors and also hold an “Entering School” ceremony. Invitations were sent to all elders in the village and distinguished guests to a feast and they all had a happy time. She also acquired some permanent property which yielded an annual income of approximately $1,000. My brother was entrusted with the administration of the income which was to pay for the expenses of the ancestral worship ceremonies, the balance for general expenses. All accomplished, they returned to Queensland.

Thereafter, our relatives, cousins and brothers came over one after the other. Each was employed according to his ability and paid according to his capacity. To the more able, greater responsibility was given; to the less able, lessor responsibility was given. It was true no one amassed a great fortune but they all became rich in the end. Realizing that “wishing to be established himself, one seeks first to establish others; wishing to be enlarged himself, he seeks first to enlarge others,” I helped some with a loan and aided others with influence. They all found their occupations and enjoyed to labour. After all, can it be denied the success was not due to my determination and disregard of the advice to return home.

From 1910 to 1911, business was normal and remained so the following year. In 1913 there occurred another great flood and inundated the land into a “watery kingdom.” Debts became hard to collect and our goods were damaged by water. The consequent loss was heavy. During 1914 to 1917 business was satisfactory and the children graduated from school. Mei Tim and Mei Kiu daily remained in the store and helped in the business. They inherited their mother’s traits for the way they kept the accounts and sold or displayed the goods was orderly and methodical. The business showed remarkable progress.

In 1918 we had a terrific storm. The wind roared and lifted the roofs off like kites. Eight or nine out of ten houses and buildings collapsed burying in the debris six out of ten inhabitants. Though our store was not wrecked and every one was safe, the slashing rain added force to the wind which soon lifted off the roof and exposed all the goods to the rain. Before the whole roof was gone, the family and employees made brave efforts to save the goods, moving this and covering that ceaselessly throughout the night. But all was in vain, as one moment the east wall needed attention the next moment the west wall was found leaking. In spite of our efforts, some damage was done.

After the storm we hastily made preparation for repairs. All available material was used which caused an intense embarrassment. Our goods were in a chaotic condition; to sell them was difficult and to discard them was waste. The mere sight was depressing and heartbreaking. Debts owing us became difficult to collect, while we had to settle whatever we owed to others. I estimated the total loss was well above four or five thousand pounds. The terror and destruction wrought had never been worse than this.

In 1919 and 1920 our customers met their bills more regularly and we gradually recovered. For the succeeding three years, business was comparatively better than before. One would liken it to eating a piece of sugar cane from top down, the sweetest part would be last. I felt more than satisfied.

As I am now growing old my eyes are becoming dim; my wife is also ill through continuous overexertion. We feel it difficult to continue our active management of the business. As it is said “from the ancient time, few men have lived to the age of seventy. Though I am still healthy and strong, I have passed seventy and come to the evening of my life. The sunset is certainly beautiful but I fear that the glow will not last long. My children have now grown up and I can entrust to them the business and relieve myself of this burden. In regard to all my business and property, I have instructed my lawyer to make an equal and proper disposition and need not here be mentioned. It is my rules of business which I fear some of you do not quite understand. Therefore I put down my ten rules as follows:

1. In purchasing goods, first of all consider the demand. Do not stock a large quantity, firstly, for fear of moths and secondly, for fear of deterioration. If the goods are in demand at profitable prices it becomes an exception. In an exceedingly cheap article, there is no harm to buy a large quantity.

2. Always serve your customers with courtesy and patience. Show them patiently as many samples as you can. If one does not suit them, offer them others. Always try to please them in order to extend the trade.

3. In wrapping up articles for the customers make sure that there are no mistakes. In case a customer complains that the figures are not correct, you should be patient to check over them again. If there be errors, apologize and make the corrections accordingly. If there be no mistakes, explain the fact with great tact so as not to displease the customer and lose his patronage.

4. When there are too many customers to enable you to attend to them all at the same time, then ask courteously some of them to wait for a while. You will thus not disappoint them and will retain their goodwill.

5. When a customer becomes lax in the settlement of his account, sound business demands collection. However, one should employ careful terms to avoid annoyance. If letters nor calls result in payment, devise some other scheme. Finally request him to pay by installments should he keep postponing. Do not lose control for a moment and resort to legal procedure for a lawsuit will eventually bring evil. Beware! Beware!

6. At closing hour, shut and lock all doors and windows and inspect the store yourself to avoid thieves from breaking in. Also take pain to guard against fires, they are always disastrous.

7. This town is located in a low region and susceptible to floods. In case of an incessant heavy rain which does not clear for days during the first or fifteenth of each moon when the tide is high and you predict the water will rise and flood the town, be prepared and remove all goods to an upper floor. It will avoid the confusion when the floods do come and damage the goods. The loss thus brought about is unthinkable.

8. Influence people by your virtue and do not subdue them by force. “They who encounter men with smartness of speech for the most part procure themselves hatred. If there is any misunderstanding among the members of the store, either assistants, brothers or sisters, the best way is to endure it for the time and explain afterwards. Make them understand and reconcile. This is a good policy.

9. In your dealing with people, calmness is to be prized. If you succeed in this, prosperity may be expected in a short time.

10. If a matter does not concern you, do not forcibly interfere. It is an old saying that it is the mouth which causes shame and hostilities. If one does not meddle with anything outside his own sphere, he will be free from sorrow throughout his life. So beware of it!

Oh! Hing, my son, guide your younger brothers, Wing and Wah and obey my commands. Each manage your own property, and do not dispute. To be able to practise economy and diligence is the secret of keeping an estate as well as founding it. Don’t forget that if one does not alter the way of his father, he is considered filial. The Book of Poetry said, For such filial piety without ceasing, there will ever be conferred blessing on you. Do exert yourselves in that direction. The experience of the past serves as the guide for the future; if you do not know the hardship I have gone through, read the above pages. And if you want to perpetuate my work without laxity, observe the ten rules of business. Oh! Hing, Oh! Hing, carefully attend to all your affairs. Hereafter I retire with your mother.

TAAM SZ PUI (A native of Ny Chuen, Nam Hoi District, Kwongtung, China)

Written in my 71st year at Innisfail (formerly Johnson River), Queensland February, 1925.