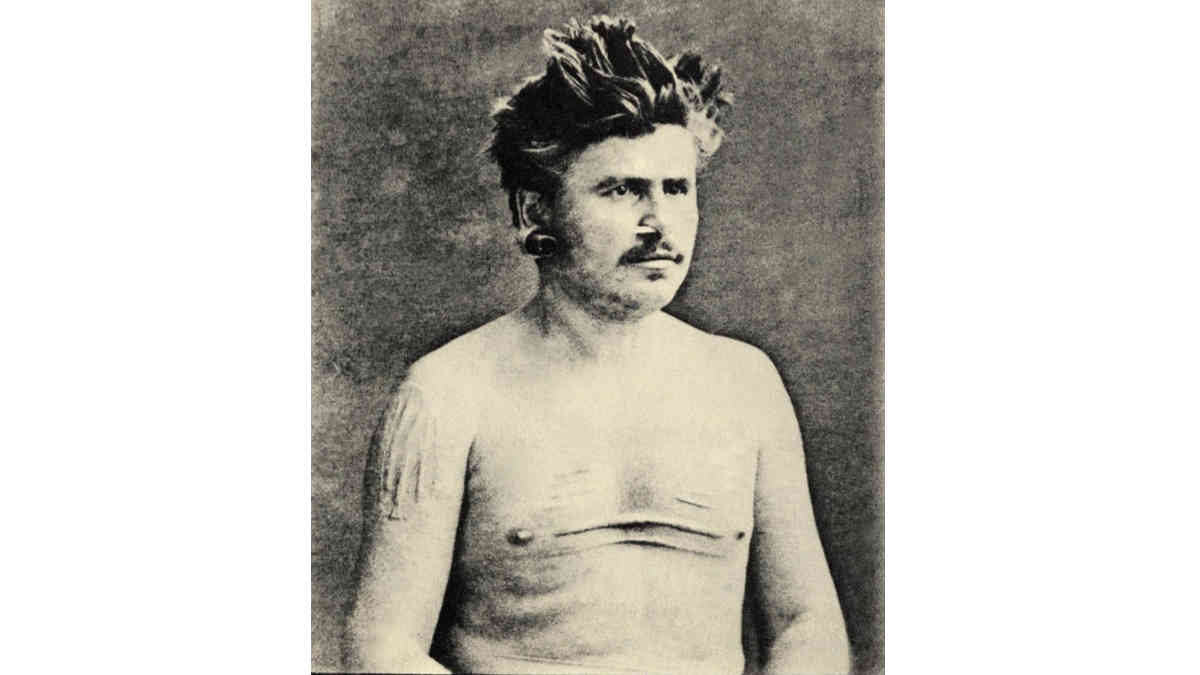

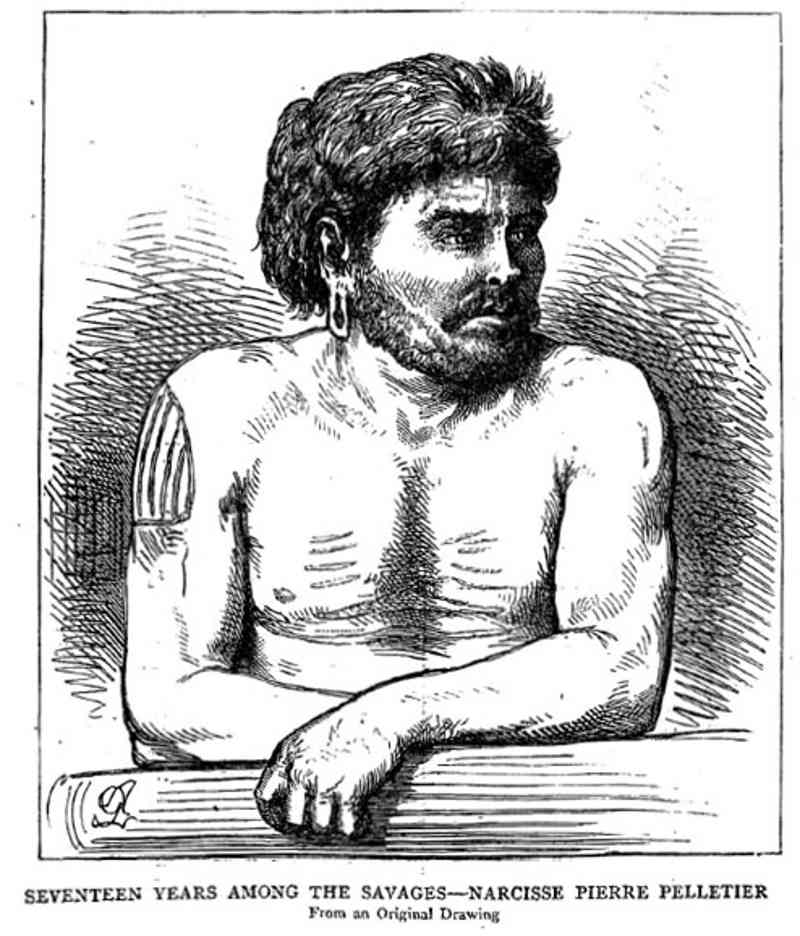

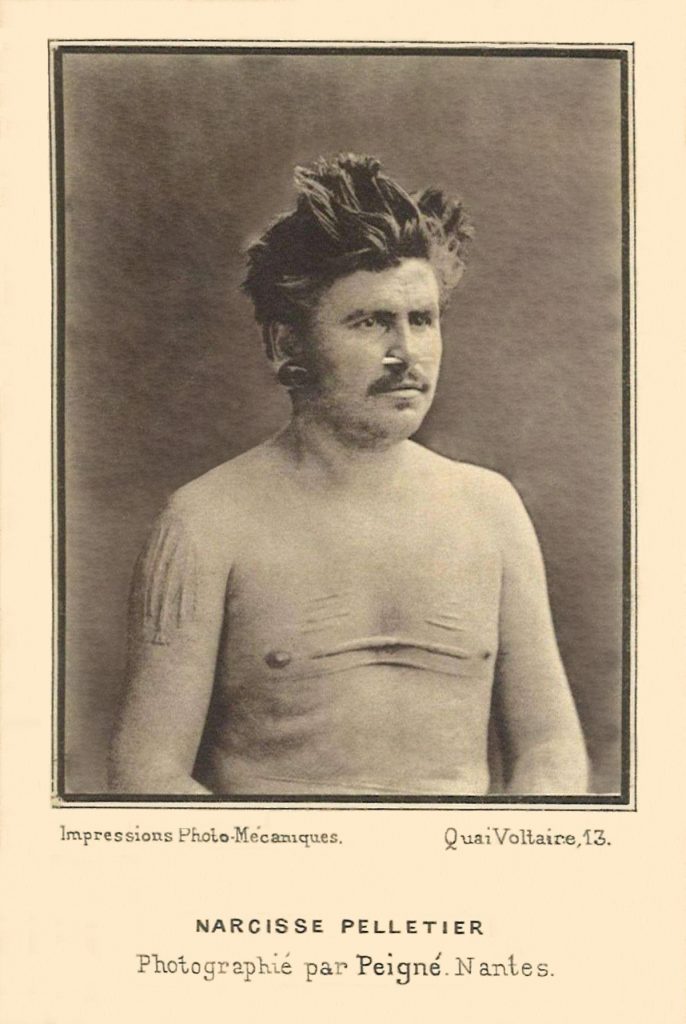

In 1875, the captain and crew of a ship dropped anchor off the remote northeastern coast of Australia to replenish their water supply. Among a group of Aboriginal warriors encountered on land stood a young man who, like the others, was naked, and decorated with ritual scars on his chest and arms that were a sign of Aboriginal manhood. One of the man’s earlobes was distended, and pierced with a four-inch-long piece of wood, and the septum of his nose was pierced with a long piece of bone. In this respect too, he did not stand out as unusual among his companions.

What caught the attention of the sailors was the man’s light skin, and unmistakably European hair and facial features. He was known among his aboriginal companions as Amglo, but up to the age of 14 years, his name had been Narcisse Pelletier.

Shipwreck and Survival

Narcisse Pelletier was born in a harbour town on the west coast of France in 1844. In August, 1857, the 13-year-old Narcisse joined the crew of the ship Saint-Paul as a cabin boy. The Saint-Paul sailed for Bombay and Hong Kong with a cargo of Bordeux wine. In Hong Kong, 317 Chinese passengers boarded the Saint-Paul for passage to the Australian goldfields.

The Saint-Paul struck a reef while sailing a perilous route between the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. The passengers and crew abandoned ship and sought refuge on a small, waterless island around one kilometer off the coast of Rossel Island. After attempts to fetch water from Rossel was thwarted by an attack by the natives, the Captain of the Saint-Paul, Emmanuel Pinard, and his crew, boarded a longboat during the night, and left the Chinese to their own fate.

The cabin boy wasn’t included in the crew’s escape plan, but having overheard the crew discussing their intentions, Pelletier managed to jump into the boat as they were leaving. The nine men aboard the longboat had just a little flour and some water stored in three pairs of seamen’s boots to tide them over a 12-day journey across the Coral Sea.

Suffering from starvation and dehydration, the crew eventually reached the coast of Cape York Peninsula, at the northeastern point of the Australian continent, which at that time was thousands of miles north of any European settlement. They made several landings on the place Pelletier’s biographer called “Endeavour Land.1” Finding scant food and water, two men close to death were left in the boat, and Pelletier himself, still suffering from a serious a head injury after being hit with a rock during the battle with the natives of Rossel Island, was growing weaker, and finding it difficult to keep up with the others on a trek in the search of water.

Pelletier was lagging behind when the men found a small waterhole. By the time Pelletier caught up with them, they had quenched their thirst, but there was no water left for the cabin boy. Pelletier was told to stay and rest while the waterhole refilled. The men promised they would return for him after searching for fruit.

But nobody returned for him. After spending the night beside the empty waterhole, which did not refill, Pelletier returned to the place the boat had landed only to find that the boat and crew were gone. The 14-year-old boy stood alone, thirsty and starving, on the remote coast of a wild land whose only occupants were wild black men he believed would probably kill and eat him.

Pelletier appears to have had no choice but to approach the the people he so feared, as he was going to die anyway. Narcisse followed footprints of the natives from the beach that led to well-beaten tracks a short distance inland. The following day Pelletier met with three black women, completely naked, who ran away upon seeing him.

While not greatly reassured by the sight of them, Pelletier did not know if he ought to rejoice or despair about their disappearance, since he was set to die of fatigue and starvation if nobody came to his rescue.2

Soon, two middle-aged men appeared, armed and cautious. Determining that the boy was in such a weakened state that he constituted no threat, they approached him. One man asked for the tin cup Pelletier was holding. Pelletier handed it over, then added a white handkerchief as an additional gift in the hope it would convince the men to help him.

The men gave Pelletier some water, gestured that they would give him food, and helped him walk to their camp. The two men were brothers-in-law, one of whom was named Maademan. The men gave Pelletier some coconunt, and their wives, who were still terrified of the white boy, went out to gather fruit for him to eat.

The following morning Pelletier woke up alone, and feared that he had been abandoned again. Among his fears was the possibility that the natives’ acts of friendship were merely a ruse, and that perhaps they had other intentions, such as killing him and feasting on his flesh.

However, the aborigines had merely gone to gather fruit for his breakfast, and not only did they feed him, Maademan, who had two wives, but no children, adopted Pelletier and gave him the name Amglo.

Pelletier, wishing to pay his debt of gratitude to his new family, took them to the place where the crew had gone to quench their thirst, and where they had left several blankets. The savages seized them, shouting out with joy and again making the most vigorous displays of friendship to Pelletier. On seeing these declarations of affection, whose sincerity he could no longer doubt, all fear was banished from his heart.3

Life as an Aboriginal Australian

Amglo was introduced to the rest of the tribe as Maademan’s adopted son. While he had difficulty adapting to their diet at first, gradually he regained his health and strength. Amglo learned their ways of fishing, hunting, and survival.

After a certain time all that distinguished him from them was the colour of his skin and the shirt and trousers which covered his body. It was not long before this last feature disappeared. One day while he was bathing, the savages tore up his clothes and shared out the shreds of material to use as a decoration for their foreheads.4

By the time he was 15 years old, Amglo was fluent in the language and ways of the Ohantaala – a clan consisting of around 30 men and their wives and children. The lifestyle of the Ohantaala could not be further from that of a western European of the 19th century. The Aboriginal people of Cape York did not build houses, and although they sometimes constructed simple shelters, most often slept out in the open, completely naked at all times day or night, and in all weather conditions. They did not farm or grow food. Nor did they keep livestock. Every day, they hunted, fished, and gathered whatever they needed for that day, and at most, the following day.

While Amglo seemed to be accepted and liked by by most of the tribe, he was often teased for the color of his skin, and odd habits such as regularly washing his hands. Inevitably, there were some “whose feelings of repulsion towards him were obvious.”5

Amglo found a close and constant friend in his cousin Sassy – Maademan’s brother’s son – who was around the same age as Amglo. In fulfilling their duties to their fathers, they would often be together, fishing, hunting, etc.

Sassy possibly saved him from serious injury or death when Amglo had a conflict with another man over the division of turtle meat:

One of the savages thought that he had taken the lion’s share and, as he claimed to have rights in it himself, he threw himself upon the defenseless Pelletier. The man was even making ready to drive his arrow6 into him when Sassy ran up and, threatening him with his own weapon, forced him to let go. Pelletier, who did not have his weapons with him, luckily found an arrow to hand with which he was able to defend himself. Their friends ran up at the sound of the fighting and separated the combatants, who had only wounded each other superficially.7

Amglo’s ability to recall in the French language began to fade, and his childhood memories of life in France receded until:

the days of his childhood appeared to him to belong to such a distant past that he was sometimes inclined to wonder if Saint-Gilles really did exist, if its church, its harbour and its ships were not just a figment of his imagination.8

Amglo suffered from frequent, severe headaches, that over a long time manifested every three days. This may have been due to the head injury he had suffered in the battle on Rossel Island. For this malady he was treated by a traditional method which involved bleeding. A piece of broken bottle was used to make vertical cuts in his forehead from the hairline to the space between the eyes. Bleeding was encouraged by tapping the surrounding tissue with a wooden twitch, then a particular herb was chewed and dabbed on the wound. According to Pelletier, “the treatment was a complete success.”9

As well as the scars received in the course of traditional medical treatment, Pelletier also had scars and piercings related to ritual and adornment. His right ear lobe had become distended from wearing a wooden cylinder made from a piece of bamboo, and the septum of his nose was also pierced and decorated with a long piece of bone.

Cicatrices made by cutting and rubbing charcoal into the wound formed thick, horizontal welts across his chest, and vertical scars on his upper arms. However, unlike the other members of his tribe, Pelletier never had one of his incisor teeth knocked out.

Pelletier said that he had participated in no less than 12 battles with neighboring tribes in the 17 years he lived with the Ohantaala, most of them sparked by fights over women.

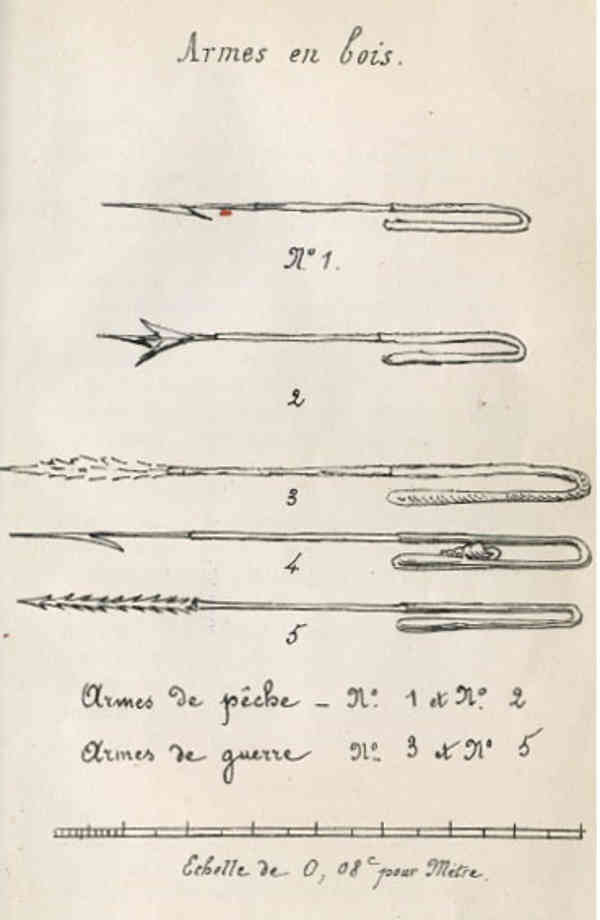

The Ohataala did not hunt, but survived exclusively by fishing. Amglo became proficient in the use of spears to catch fish. He would stand in shallow water and skewer fish with sharp-tipped, barbed spears, or go to sea in an outrigger canoe to hunt for larger fish, turtle, and dugong.

European Contact

The time that Pelletier spent with the aboriginal people of Cape York coincided with early contact between the aborigines and European mariners. English sailors were probing the area in search of trepang (sea cucumbers), pearls, and other valuable marine resources. According to Pelletier, the aborigines had prized items such as beads or colorful cloth obtained in trade with the English. They also used pieces of broken glass and iron obtained from shipwrecks. Pelletier also mentioned that the Ohataala had taken a liking to “biscuit” which they obtained from the English in exchange for fish or shellfish.

The British mariners also brought other changes to the culture of the Ohataala. Pelletier explained that fishing was an exclusively male activity, but that until recent times, women had been able to go to Night Island to gather fish caught by the men. However, this changed after the following incident:

One day when the catch had been abundant and the husbands had returned to land, leaving their wives to bring back the fish which they had caught, ten women boarded a canoe and landed on the little island where the men had left the fish. Barely had they set foot on shore when they noticed an English ship which was heading in their direction. Very frightened by the sight of it, and not having time to get back to their canoe, they made a hasty escape and hid in the woods covering the island. The English landed straight away.

Nothing which had just occurred escaped the eye of the savages and they were therefore extremely fearful: they were convinced that their wives were going to be taken from them and that they would never see them again. When night had fallen, the men, taking the greatest precautions, went to the island. How great was their surprise and joy in finding their dear wives again! They soon consoled themselves about the loss of their canoes and the fish, which the English had seized.11

Despite the possibility of making contact with these mariners, Pelletier seems to have made no attempts to do so. Merland’s record of Pelletier’s life with the aboriginals suggests that the other aboriginal men prevented him having contact with the white men.

For fear that he might try to escape, the natives had long been careful to keep him away when they had dealings with the whites. On only one occasion had he seen other white men, who, on reaching land, gave gifts to the blacks in exchange for those they received from them. In vain had he wanted to approach them; he had been kept away from them. If, when the sea was calm, his brothers of the tribe sighted a foreign boat, they always made towards it with the same aim, but at such times Pelletier remained on land.

However, with time, the misgivings of the savages had ceased, and they no more feared that Pelletier would make his escape from them than he dreamt of doing so himself.12

It is quite fascinating to find that the close encounter with the white men mentioned by Pelletier was actually reported, and was recently discovered in the historical record. John MacGillivray, a naturalist traveling on the Julia Percy in search for trepang and sandalwood, wrote of his visit to the exact location of Amglo’s tribe: “One man was light enough to have been a half-caste, but he shunned observation, and got out of the way when I wished to examine him closely.” The incident occurred in 1860, when Amglo was 16 years old and had lived with the Aborigines for two years.13

Return to Civilization

On April 11, 1875, an English ship, the John Bell cast anchor at Night Island. A long boat from the ship approached the land and two black14 crew members offered gifts of biscuit, tobacco, a knife, and a necklace to the Aboriginals. Shocked at seeing a white man among them, the crew returned to the ship to inform the captain.

The captain ordered the crew members to offer “dazzling” gifts if only the white man would come aboard to fetch them. Amglo was suspicious of the sailors’ intentions, but Maademan ordered him to go, and to jump overboard and swim back if the English attempted to detain him.

Thus, lured on board the John Bell, Amglo was was kept at gun point and forced to put on clothes. The John Bell sailed away from the land of the Ohataala people and and from the life Amglo had known for the previous 17 years, in which time, the 14-year-old French boy had grown into a 31-year-old Aboriginal man.

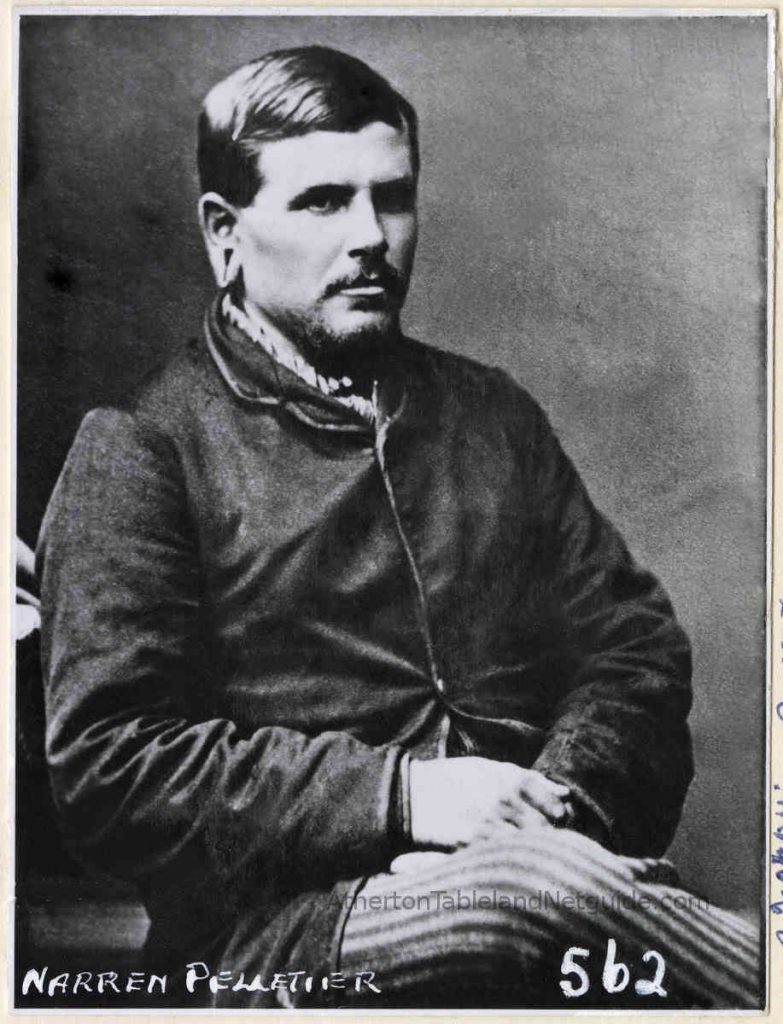

Having lost all memory of the French language, and not knowing any English, communication was difficult. The captain of the John Bell provided Amglo with paper and pen, on which he formed letters, at first in a random manner. The activity seems to have stimulated a long stagnant part of his mind, so that soon he was able to write his name, which provided an important clue as to his nationality.

The John Bell sailed to the remote British outpost of Somerset, on the tip of Cape York Peninsula, where two people resident at the time could speak some basic French. One of these men was Lieutenant Edward Connor, Assistant Admiralty Surveyor of the Royal Navy.15 Slowly regaining his native language, somebody assisted him to write a letter to his family dated May 13, 1875, a little over one month after he was lured aboard the John Bell.

Pelletier was put aboard the mail steamer RMS Brisbane, which sailed down the coast to Sydney. Aboard the ship was only one fluent speaker of French, John (later “Sir John”) Ottley. Ottley was a British Indian Army Officer of the Royal Engineers travelling from Calcutta to Rockhampton to visit relatives. Ottley’s observations provided newspaper fodder that was widely published in 187516, but even more valuable insights into the state of mind of Pelletier as he readjusted to life in the civilized world of the west were proffered by a letter Ottley wrote 48 years later, in 1923.

I have been told that in an article on the case of Narcisse Pelletier published in the London ‘Times’ shortly afterwards the writer said that I was probably the only Englishman who could claim that he had taught a Frenchman his own language. Of course I did nothing of the sort. What really happened was that by constantly talking to him in French, I succeeded in opening up the floodgates of Pelletier’s memory, and this brought to the surface a whole host of words that had long been disused and temporarily forgotten. Anyway he was a marvelously apt pupil for before we parted he was not only discoursing volubly in French but had also to a great extent recovered his knowledge of reading and writing and had acquired as well a certain number of English words in addition.17

In the original correspondences sent by Ottley and published in various newspapers in May and June of 1875, Ottley confirmed that Pelletier had been unwilling to be separated from the tribe. Narcisse told him that neither the tribe or himself wanted him to leave, but both the tribe and himself were afraid of the white men’s guns. Ottley noted that Pelletier had “long forgotten La Belle France” and had become “thoroughly identified with the blacks.”18

Pelletier was handed over to the French consul in Sydney, and met many people in the French community there. During the 38 days he stayed in Sydney he was an object of curiosity and interest, and it is said that he completely regained his ability to communicate in French. A second letter he wrote to his family while there showed a great improvement, being in his own handwriting.

If Pelletier left the Ohataala reluctantly, by the time he reached Noumea, he was thoroughly looking forward to reaching France and seeing his family again. Previously unsure if his parents were even alive, he was reassured when he met a fellow resident of Saint-Gilles, serving as a soldier in the French colony:

Marchand, whom Pelletier talks about, was a young soldier from Saint-Gilles who was serving in Noumea. His meeting, so far from his country, of a fellow countryman, had been a very pleasant experience for Pelletier. It had brought back to him all his memories of his early childhood. From then on he could think of only one thing: he wanted to see the authors of his days again as soon as possible, having long been tormented by anxiety as to whether they were alive, and who, Marchand had told him, were in good health at the time that he had left France.19

When Pelletier’s parents received the first letter he had sent from Somerset, they doubted its authenticity, fearing that someone was playing a cruel joke on them. Seventeen years previously, the Pelletiers had held a funeral ceremony for their lost son. Apparently, the survivors of the Saint-Paul reported that Narcisse had been eaten by savages.20 A newspaper report the following day removed all doubt about the authenticity of the letter, and Mrs Pelletier stopped wearing the black mourning dress she had worn for the previous 17 years.

Pelletier arrived in France on December 13, 1875, and was met by his brother at Toulon.

On 2 January he made a triumphal entry into Saint-Gilles. The whole population had come out to meet him, and his childhood friends smothered him in their embrace. I shall refrain from evoking the tender scene which deeply moved the hearts of one and all when he threw himself into the arms of his parents: no description could do it justice. Opposite their modest dwelling a bonfire awaited the new arrival and, when he came to light it, prolonged shouts of ‘Long live Pelletier!’ were heard. His father’s house was too small to receive all those who wanted to come inside and, for fear of mishap, he was obliged, to his great regret, to shut the doors.

The next day a solemn mass of thanksgiving for this happy event was celebrated in the church of Saint-Gilles, which was filled by the throng. The priest who celebrated the mass showed his emotion as he spoke, and his hand which, 32 years previously, had on the same day poured the baptismal water on to Narcisse Pelletier’s forehead, called down upon his head God’s blessing from above.21

No doubt there would have been some challenges in readapting to life in Europe. Ottley noted that on the journey to Sydney Pelletier was not yet comfortable wearing clothes, and would have preferred to have removed them. Legend in his home town says that his family once took him to a priest to be exorcised. However, his life appears to have returned to normal. He married but had no children. He was employed as a lighthouse keeper, later as a signalman in the harbour, and eventually as a clerk at customs house.

Pelletier died in 1894 at the age of 50.

Conclusion

The discovery of a white man living among the Aboriginals of Cape York caused a media buzz in Australian newspapers in the months of May and June 1875, but unlike the story of James Morrill [see previous article: “James Morrill: the first white resident of North Queensland“], who also lived 17 years with and “as” an Aboriginal between the years 1848 and 1863, interest in Pelletier’s tale quickly faded in Australia to the point where 48 years later, Archibald Meston, a prolific Queensland writer who considered himself quite an expert at all things Aboriginal, dismissed the story as an outright hoax.

The contrast between the long term reaction to the stories of James Morrill compared to that of Narcisse Pelletier, may perhaps be explained by the fact that Morrill spoke English and stayed in the colony after his return to civilization. Morrill was accessible to the media and audiences, and was a well-known resident of Bowen until his death in 1865.

Pelletier, on the other hand, spoke French, and left Australia not long after his return to civilization. His story was published in France by Constant Merland in 1865, but there was no English translation until Stephanie Anderson published her book, Pelletier: The Forgotten Castaway of Cape York, in 2009.

Footnotes, sources and citations

- Constant Merland in his book Dix-sept ans chez les sauvages : les aventures de Narcisse Pelletier, 1876, refers to the area of Australia Pelletier lived in as “Endeavour Land.” The first Europeans to see the east coast of Australia, and to spend time at Cape York Peninsula were the crew of the HMS Endeavour who spent close to two months camped at the Endeavour River to make repairs to the ship after hitting a reef off Cape Tribulation in 1770. See previous article “The First Europeans to visit North Queensland.” My references of Merland are from the translation in Anderson, Stephanie, Pelletier: The Forgotten Castaway of Cape York, Melbourne Books, 2009. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Merland in Anderson, 2009. ↩︎

- Merland uses the word “fletche” (arrow) for the Aboriginal spears. Australian Aboriginals did not use bows and arrows. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- John MacGillivray, Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Wanderings in tropical Australia. No. II. First Northern cruise’, 10 January 1862 quoted in Anderson, 2009. ↩︎

- Merland calls them “Negros” but they were no doubt Melanesians from the Torres Strait or Pacific Islands. ↩︎

- Anderson, 2009. ↩︎

- Reports based on Ottley’s correspondence were published widely in Australian newspapers in 1875, such as the South Australian Register, Monday, 7 June. ↩︎

- Extract from a letter dated 30 May 1923 written by Sir John Ottley to H. J. Dodd giving an account of

his meeting and conversations with Narcisse Pelletier on board the Brisbane in 1875, in Anderson, 2009. ↩︎ - “The Narrative of Narcisse Pelletier” was published widely including The Capricorn (Rockhampton, Queensland) Saturday, June 5, 1875. ↩︎

- Anderson, 2009. ↩︎

- According to an article in Revue de Bretagne et de Vendée, 1876, translated in Anderson, 2009. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎