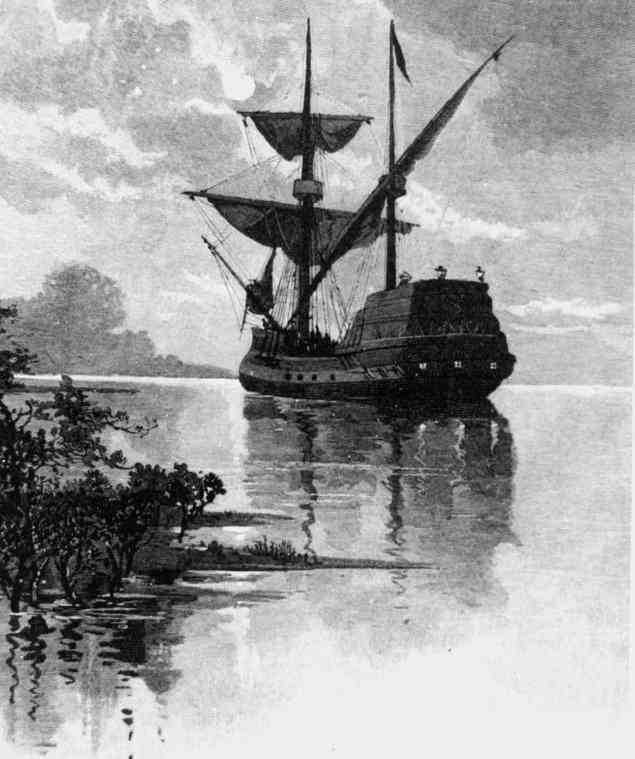

The Dutch ship Duyfken in the Gulf of Carpentaria. 19th century artist's impression (Fred B. Sibed).

The first European to make landfall in what is now known as Far North Queensland were members of a Dutch expedition led by Willem Janszoon (Jansz) on the ship Duyfken, who landed on the west coast of Cape York Peninsula near modern-day Weipa in late February, 1606. It was the first known landing of Europeans on the continent of Australia.

Assuming that the land was a southern extension of New Guinea, Janszoon mapped around 320 kilometers of the coastline. Making several landings, Janszoon found the land and its people inhospitable, having lost 10 of his men from attacks by the natives. Janszoon's mission was to explore for new trade opportunities, and not much remains in the way of records of the expedition. The ship's logs did not survive, and it was not until 1933 that Janszoon's map was found in a library in Vienna, revealing this previously unknown snippet of history.

One hundred and sixty-four years later, an entirely different kind of expedition landed on the other side of the cape, spent an extended period of time there, and made thorough and extensive records of their discoveries.

Captain James Cook led Scientific Expeditions for the British Empire.

The British Royal Navy research vessel, HMS Endeavour, commanded by Lieutenant James Cook, departed Plymouth, England in August 1768, manned and equipped for a scientific expedition aiming to fill gaps in knowledge of the geography of our planet. The first objective of the mission was to observe the transit of Venus across the sun, June 29, 1769, in Tahiti, then to proceed to 40° latitude to determine if the long-speculated great southern landmass of Terra Incognita existed there. The final order was to explore New Zealand, after which Cook could return home by whichever course he chose.

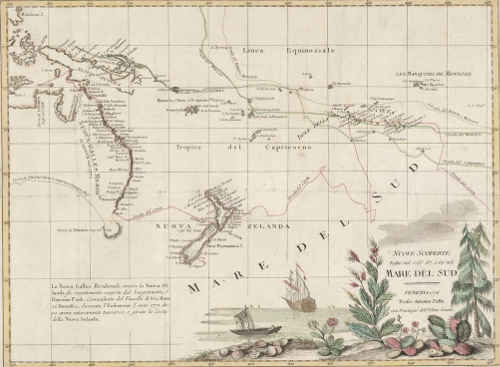

After mapping the north and south islands of New Zealand, Cook decided to return to England via the unexplored and uncharted east coast of New Holland. It was a momentous decision in the course of history.

Cook recorded the context that led to the decision, showing that history could easily have taken a different course if it weren't for the condition of the ship, the scientific curiosity of those aboard, and their desire to make new discoveries:

..all on board the ship ready for sea and being now resolved to quit this country altogether and to bend my thoughts towards returning home by such a rout as might conduce most to the advantage of the service I am upon I consulted with the officers upon the most eligible way of putting this in execution. To return by the way of Cape Horn was what I most wish'd because by this rout we should have been able to prove the existence or non existence of a Southern Continent which yet remains doubtfull, but in order to ascertain this we must have kept in a high latitude in the very depth of winter but the condition of the ship in every respect was not thought sufficient for such an undertaking. For the same reason the thoughts of proceeding directly to the Cape of Good Hope was laid a side especialy as no discovery of any moment cound be hoped for in that rout. It was therefore resolved to return by way of the East Indies by the following rout -upon leaving this coast to steer to the westward until we fall in with the East Coast of New Holland and than to follow the deriction of that Coast to the Islands discover'd by Quiros.

Map made by Antonio Zatta using Cook's charts of New Zealand and the east coast of New Holland.

The Endeavour reached the southeast coast of New Holland on April 19, those aboard becoming the first Europeans on record to have seen the east coast of the continent.

Cook, a master cartographer, made a meticulous map as the expedition plied north. Nine days later, the Endeavour made its first landing on the continent, pulling in at what Cook would name "Stingray Harbor," but would later change to "Botany Bay."

The explorers spent eight days in Botany Bay. The scientists aboard, including the astronomer, Charles Green, the botanist, Joseph Banks, the Swedish naturalist, Daniel Solander, the Finnish naturalist, Herman Sporring, and artist, Sydney Parkinson, made daily excursions into the coastal forest to collect animal and plant specimens.

Members of the ship's crew of 73, and 12 marines, fished, gathered firewood and water, hunted waterfowl and game.

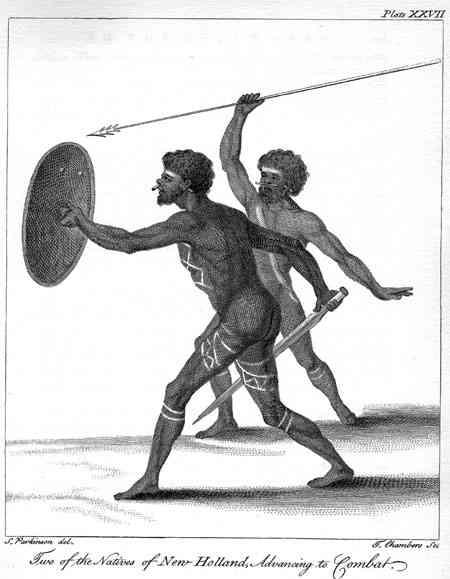

Sketch by Sydney Parkinson titled "Two of the Natives of New Holland, Advancing in Combat.

Attempts to make contact with the numerous natives failed, with the natives throwing spears and rocks and running away at any approach. Offers of gifts were rejected, and even offerings of beads, mirrors, combs, cloth, and trinkets left in huts or on the ground remained untouched after several days.

Banks and company collected many specimens of plants hitherto unknown to science, and shot some birds, but no significant discoveries of Australia's unique fauna were made. On May 1, they spotted an animal the size of a rabbit, but no further description was made:

We saw one quadruped about the size of a Rabbit, My Greyhound just got sight of him and instantly lamd himself against a stump which lay conceald in the long grass; we saw also the dung of a large animal that had fed on grass which much resembled that of a Stag; also the footsteps of an animal clawd like a dog or wolf and as large as the latter; and of a small animal whose feet were like those of a polecat or weesel. The trees over our heads abounded very much with Loryquets and Cocatoos of which we shot several; both these sorts flew in flocks of several scores together.

The Endeavour's visit to Botany Bay was significant in many ways. It was the first time Europeans were known to have stepped on the east coast of the largely unknown continent. Many significant botanical specimens were discovered and collected there. Botany Bay was to become a household name the world over after a decision was made, 16 years after the visit of the Endeavour, to establish a penal colony there. But compared to the expedition's extended stay on the Endeavour River in Far North Queensland, the time the expedition spent at Botany Bay was relatively short, the number and significance of discoveries of flora and fauna was relatively small, and attempts to make contact with the native people at Botany Bay were a complete failure.

Specimen collected by Banks at Botany Bay, and illustration by Sydney Parkinson of Banksia serrata.

The Endeavour left Botany Bay May 6. One more landing was to be made, at Bustard Bay (today "Town of 1770") on May 23 before the expedition was forced by an accident to spend nearly two months at the Endeavour River at the site of today's Cooktown.

Cook clung to the coast as he plied north, bringing him inside what is now known as the Great Barrier Reef, and the further north one sails, the closer the reef comes to the coast.

The evening of Monday, June 11, was a fine moonlit night, and rather than casting anchor and stopping for the night, Cook decided to carefully perservere forward with shortened sail and the crew constantly sounding the depth. The Endeavour had just passed a cape that Cook was to name "Cape Tribulation" for what happened next:

...having the advantage of a fine breeze of wind and a clear moon light night in standing off from 6 untill near 9 o'clock we deepen'd our water from 14 to 21 fathom when all at once we fell into 12, 10 and 8 fathom. At this time I had every body at their stations to put about and come too an anchor but in this I was not so fortunate for meeting again with deep water I thought it there could be no danger in standing on -before 10 o'clock we had 20 and 21 fathom and continued in that depth untill a few minutes before 11 when we had 17 and before the man at the lead could heave another cast the ship struck and stuck fast.

The 94 men aboard the Endeavour were in a perilous predicament which was clearly described in the journal of Sydney Parkinson:

We were, at this period, many thousand leagues from our native land, (which we had left upwards of two years,) and on a barbarous coast, where, if the ship had been wrecked, and we had escaped the perils of the sea, we should have fallen into the rapacious hands of savages. Agitated and surprised as we were, we attempted every apparent eligible method to escape, if possible, from the brink of destruction. The sails were immediately handed, the boats launched, the yards and topmasts struck, and an anchor was carried to the southward: the ship striking hard, an-other anchor was dispatched to the south-west. Night came on, which providentially was moon-light, and we weathered it out as patiently as possible, considering the dreadful suspense we were in.

Fortunately the weather and sea conditions remained calm, otherwise the ship may have broken up against the reef. All hands were put to work, manning two pumps in shifts of 15 minutes, and lightening the ship by throwing anything that could be spared overboard. Stone ballast, water casks, cannons, spoiled provisions, firewood, and so on, were cast overboard, with Cook estimating that they had lightened the ship by 40 or 50 tons on the morning of June 12, but as this was not considered sufficient, they continued to throw out "anything we could think of" [Cook's Journal]. However, the tide dropped, and at around noon, the ship heeled over to starboard. As the tide rose in the late afternoon, the ship righted again, and at around 10:00 pm, with men hauling on block and tackle attached to anchors, while others desperately manned the pumps to keep up with the leaking hull, the Endeavour came free of the reef.

Cannon from the Endeavour recovered from the Endeavour Reef in 1969 and on display at the Australian National Museum.

This desirable event gave us spirits; which, however, proved but the transient gleam of sunshine, in a tempestuous day; for they were soon depressed again, by observing that the water increased in the hold, faster than we could throw it out; and we expected, every minute, that the ship would sink, or that we should be obliged to run her again upon the rocks.

Fortunately, with men freed from efforts to haul the ship off the rocks able to join those pumping water, the crew "gained upon the leaks," which by now had filled the hold with 3 feet, 9 inches of water. A sail filled with wool and oakum mixed with sheep dung and horse dung was drawn across the damaged hull to seal the leak enough that one pump was sufficient to keep the ship afloat.

Three smaller boats were carried by the Endeavour - a pinnace, a longboat, and a yawl. Two of these were sent to probe for a passage and suitable place to land and repair the ship.

On June 14 a suitable place was found on a bend a short distance upstream from the mouth of a river. The passage was narrow, and not very deep. Cook took it upon himself to survey and mark the channel with buoys. The wind and tides were unfavorable for entering the harbor until June 18.

Having passed the perils of the previous days off Cape Tribulation, the men's spirits were buoyed at the prospect of spending time ashore. Looking towards the prospective landing place on the evening of June 15, Joseph Banks spotted a campfire, "which made us hope that the necessary length of our stay would give us the opportunity of being acquainted with the Indians who made it." [Banks Journal, June 15]

A view of Endeavour River on the coast of New Holland, where the ship was laid on shore, in order to repair the damage which she received on the rock, engraving by William Byrne of a lost drawing, probably by Sydney Parkinson.

On June 18, touching the bottom twice, and getting stuck for a time, the Endeavour was maneouvered to a steep bank on the south side of the river, tied to a tree onshore, and emptied of cargo and provisions. Two tents were erected on shore, one for storing provisions and one for lodging sick crew members, of which there were eight or nine "afflicted with different disorders but none very dangerously ill" [Cook's Journal, June 19, 1770].

Among the sick was Tupaia (spelled by Cook and Banks "Tupia"), a polynesian navigator who had joined the expedition in Tahiti, and assisted with communication on other polynesian islands, including New Zealand. While waiting to land, Tupaia had symptoms of severe scurvy, according to Joseph Banks' description, and the astronomer Charles Green was also ill, but once onshore, Tupaia appeared to immediately recover, and James Cook observed him angling, noting that "he livd intirely on what he caught" but "poor Mr Green still very ill.

A forge was set up on the shore, and the armourer and his mate set about making nails to repair the ship. Banks immediately set out to gather and dry plants "which we had hopes of as many as we could muster during our stay." [Banks' Journal, June 20, 1770]

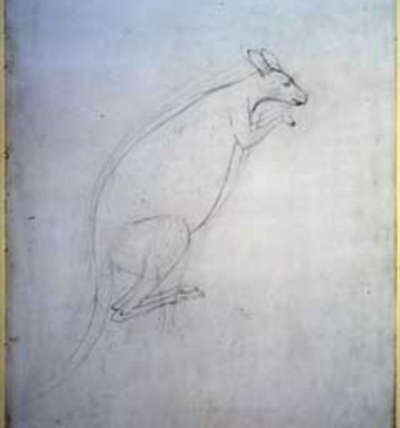

First sketch of a kangaroo made by Sydney Parkinson, June 23, 1770, at Endeavour River, Far North Queensland.

On June 22, the animal that was to become the iconic symbol of the nation of Australia was spotted by Europeans for the first time.

The people who were sent to the other side of the water in order to shoot pigeons saw an animal as large as a grey hound, of a mouse colour, and very swift...

The animal was seen again the following day, as recorded in both Banks' and Cook's journals, and on June 24, Banks spent the day gathering plants and "hearing descriptions of the animal which is now seen by every body." [Banks' Journal June 24, 1770] On the same day, Cook saw one of the strange animals with his own eyes, describing it thus:

I saw my self this morning a little way from the ship one of the Animals before spoke off, it was of a light Mouse colour and the full size of a grey hound and shaped in every respect like one with a long tail which it carried like a grey hound in short I should have taken it for a wild dog, but for its walking or runing in which it jump'd like a Hare or a dear. Another of them was seen to day by some of our people who saw the first, they describe them as having very small legs and the print of the foot like that of a goat but this I could not see my self because the ground the one I saw was upon was too hard and the length of the grass hinderd my seeing its legs.

On June 25, Joseph Banks too, could provide an eyewitness account of the animal; an animal so strange that he struggled to describe it:

In gathering plants today I myself had the good fortune to see the beast so much talkd of, tho but imperfectly, he was not only like a grey hound in size and running but had a long tail, as long as any grey hounds, what to liken him to I could not tell, nothing certainly that I have seen at all resembles him.

Second sketch of kangaroo made by Sydney Parkinson while at Endeavour River, Queensland in 1770

Days and weeks passed by, and the europeans still had no name for the unusual animal. On July 6, Banks, Lieutenant Gore, and three men set off in one of the boats to explore up river for two or three days, with the goal "to try to kill some of the animals we have seen about this place." [Cook's Journal, July 6, 1770] On the first day "we saw 3 animals of the countrey but could not get one." [Banks' Journal, July 6, 1770]

The following day, the party continued in their quest to bring down one of the animals:

We walkd many miles over the flats and saw 4 of the animals, 2 of which my greyhound fairly chas'd, but they beat him owing to the lengh and thickness of the grass which prevented him from running while they at every bound leapd over the tops of it. We observd much to our surprize that instead of Going upon all fours this animal went only upon two legs, making vast bounds just as the Jerbua (Mus Jaculus) does.

On Saturday, July 14, Liutenant John Gore shot and killed one of the animals, finally giving the intrepid Europeans an opportunity to make a close examination:

Mr. Gore, being in the Country, shott one of the Animals before spoke of; it was a small one of the sort, weighing only 28 pound clear of the entrails; its body was long; the head, neck, and Shoulders very Small in proportion to the other parts. It was hair lipt, and the Head and Ears were most like a Hare's of any Animal I know; the Tail was nearly as long as the body, thick next the Rump, and Tapering towards the End; the fore Legs were 8 Inches long, and the Hind 22. Its progression is by Hopping or Jumping 7 or 8 feet at each hop upon its hind Legs only, for in this it makes no use of the Fore, which seem to be only design'd for Scratching in the ground, etc. The Skin is cover'd with a Short, hairy furr of a dark Mouse or Grey Colour. It bears no sort of resemblance to any European animal I ever saw; it is said to bear much resemblance to the Jerboa, excepting in size, the Jerboa being no larger than a common rat.

The following day, the officers made a meal of the unusual animal, Banks commenting "The beast which was killed yesterday was today dressed for our dinners and proved excellent meat." Cook made no mention of the meal in his journal.

On July 27, Banks went out on a hunt focused on getting another one of the unusual animal. Lieutenant Gore again succeeded in bringing down a large specimen weighing 84 lb, but the following day Banks expressed his disappointment with the meal:

Dind today upon the animal, who eat but ill, he was I suppose too old. His fault however was an uncommon one, the total want of flavour, for he was certainly the most insipid meat I eat.

Sydney Parkinson included the word "kangooroo" in a list of aboriginal vocabulary he made in early July, and on August 4, the day the expedition left the Endeavour River, Cook recorded in his journal that the natives call call the animal a "kangooroo or Kanguru."

While anchored and waiting to enter the harbor prior to June 18, not only fires were observed, but natives were seen walking on the beach. After landing however, a few huts were found, apparently unoccuppied for quite some time, but there were no signs of human activity. On June 29, a party led by Lieutenant Gore went inland four or five miles, and reported seeing footprints, and coming across fires still lit. On July 5, Joseph Banks and Tupaia went exploring the beach on the northern side of the river. While Banks was examining and collecting plants, Tupaia wandered off with the gun to shoot birds or game. Tupaia returned and reported that he had seen two natives digging for some kind of roots, but they ran away upon seeing him.

A pencil and watercolor depiction of Australian aborigines in bark canoes on the Endeavour River in 1770, made by Tupaia. British Library.

While Banks was on his expedition upriver on July 6, he had spotted a native camp, and hoped to make contact with the people.

Before our things were got up out of the boat we observd a smoak about a furlong from us: we did not doubt at all that the natives, who we had so long had a curiosity to see well, were there so three of us went immediately towards it hoping that the smallness of our numbers would induce them not to be afraid of us; when we came to the place however they were gone, probably upon having discoverd us before we saw them. The fire was in an old tree of touchwood; their houses were there, and branches of trees broken down with which the Children had been playing not yet wither'd; their footsteps also upon the sand below the high tide mark provd that they had very lately been there; near their oven, in which victuals had been dressd since morn, were shells of a kind of Clam and roots of a wild Yam which had been cookd in it. Thus were we disapointed of the only good chance we have had of seing the people since we came here by their unacountable timidity, and Night soon coming on we repaird to our quarters...

On Banks and company's return to the Endeavour they learned that a native's fire had been seen around a mile and a half away the previous day, and that two natives had appeared on the other side of the river in the morning. Two days later, the explorers finally made contact with Australian native peoples for the first time.

Four Indians appeard on the opposite shore; they had with them a Canoe made of wood with an outrigger in which two of them embarkd and came towards the ship but stop'd at the distance of a long Musquet shot, talking much and very loud to us. We hollowd to them and waving made them all the signs we could to come nearer; by degrees they venturd almost insensibly nearer and nearer till they were quite along side, often holding up their Lances as if to shew us that if we usd them ill they had weapons and would return our attack. Cloth, Nails, Paper, &c &c. was given to them all which they took and put into the canoe without shewing the least signs of satisfaction: at last a small fish was by accident thrown to them on which they expressd the greatest joy imaginable, and instantly putting off from the ship made signs that they would bring over their comrades, which they very soon did and all four landed near us, each carrying in his hand 2 Lances and his stick to throw them with. Tupia went towards [them]; they stood all in a row in the attitude of throwing their Lances; he made signs that they should lay them down and come forward without them; this they immediately did and sat down with him upon the ground. We then came up to them and made them presents of Beads, Cloth &c. which they took and soon became very easy, only Jealous if any one attempted to go between them and their arms. At dinner time we made signs to them to come with us and eat but they refusd; we left them and they going into their Canoe padled back to where they came from.

In the AM 4 of the Natives came down to the sandy point on the north side of the harbour, having along with them a small wooden Canoe with outriggers in which they seemd to be employ'd striking fish &C some were for going over in a boat to them but this I would not suffer but let them alone without seeming to take any notice of them, at length 2 of them came in the Canoe so near the Ship as to take some things we throw'd them, after this they went away and brought over the other two and came again along side nearer then they had done before and took such trifles as we gave them. after this they landed close to the Ship and all 4 came went a shore carrying their arms with them, but Tupia soon prevaild upon them to lay down their arms and come and set down by him after which most of us went to them and made them again some presents and stay'd by them untill dinner time when we made them understand that we wasere going to eat and ask'd them by signs to go with us but this they declined and as soon as we left them they went away in their canoe. one of these men was something above the Middle age, the other three were young, none of them were above 5 ½ feet high and all their features limbs proportionately small, they were wholy naked their skins the Colour of wood soot ^or a dark chocolate colour and this seem'd to be their natural colour, their hair was black, ^lank and crope'd short and neither wooly nor frizled nor did they want any of their fore teeth as Dampier has mentioned those did he saw on the western side of this Country, Some part of their bodies had been painted with red and one of them had his uper lip and breast paint with streakes of white which he called Carbanda: their features were far from being disagreeable, the Voices were soft and tunable and they could easily repeat many words after us, but neither us nor Tupia could understand one word they said.

The following day, the natives returned with a gift reciprocal to the one they had appreciated the day before:

Indians came over again today, 2 that were with us yesterday and two new ones who our old acquaintance introduc'd to us by their names, one of which was Yaparico. Tho we did not yesterday Observe it they all had the Septum or inner part of the nose bord through with a very large hole, in which one of them had stuck the bone of a bird as thick as a mans finger and 5 or 6 inches long, an ornament no doubt tho to us it appeard rather an uncouth one. They brought with them a fish which they gave to us in return I suppose for the fish we had given them yesterday. Their stay was but short for some of our gentlemen being rather too curious in examining their canoe they went directly to it and pushing it off went away without saying a word.

In the morning four of the natives made us a nother short visit 3 of them had been with us the preceeding day and the other was a stranger - one of these men had a hole through the Bridge of his nose in which he stuck a peice of bone as thick as my finger, seeing this we examined all their noses and found that they had all holes for the same purpose, they had likewise holes in their ears but no ornaments hanging to them, they had bracelets upon their arms made of hair and like hoops of small cord; they some times must wear a kind of fillet about their heads for one of them had applied some part of an Old shirt which I had given them to this use.

On the third day, the natives came again:

Indians came again today and venturd down to Tupias Tent, where they were so well pleasd with their reception that three staid while the fourth went with the Canoe to fetch two new ones; they introduc'd their strangers (which they always made a point of doing) by name and had some fish given them. They receivd it with indifference, signd to our people to cook it for them, which was done, and they eat part and gave the rest to my Bitch. They staid the most part of the morning but never venturd to go above 20 yards from their canoe. The ribbands by which we had tied medals round their necks the first day we saw them were coverd with smoak; I suppose they lay much in the smoak to keep off the Musquetos. They are a very small people or at least this tribe consisted of very small people, in general about 5 feet 6 in hight and very slender; one we measurd 5 feet 2 and another 5 feet 9, but he was far taller than any of his fellows; I do not know by what deception we were to a man of opinion, when we saw them run on the sand about _ of a mile from us, that they were taller and larger than we were. Their colour was nearest to that of chocolate, not that their skins were so dark but the smoak and dirt with which they were all casd over, which I suppose servd them instead of Cloths, made them of that colour. Their hair was strait in some and curld in others; they always wore it croppd close round their heads; it was of the same consistence with our hair, by no means wooly or curld like that of Negroes. Their eyes were in many lively and their teeth even and good; of them they had compleat setts, by no means wanting two of their fore teeth as Dampiers New Hollanders did. They were all of them clean limn'd, active and nimble. Cloaths they had none, not the least rag, those parts which nature willingly conceals being exposd to view compleatly uncoverd; yet when they stood still they would often or almost allways with their hand or something they held in it hide them in some measure at least, seemingly doing that as if by instinct. They Painted themselves with white and red, the first in lines and barrs on different Parts of their bodies, the other in large patches. Their ornaments were few: necklaces prettyly enough made of shells, bracelets wore round the upper part of their arms, consisting of strings lapd round with other strings as what we Call gymp in England, a string no thicker than a packthread tied round their bodies which was sometimes made of human hair, a peice of Bark tied over their forehead, and the preposterous bone in their noses which I have before mentiond were all that we observd. One had indeed one of his Ears bord, the hole being big enough to put a thumb through, but this was peculiar to that one man and him I never saw wear in it any ornament. Their language was totaly different from that of the Islanders; it sounded more like English in its degree of harshness tho it could not be calld harsh neither. They almost continualy made use of the Chircau, which we conceivd to be a term of Admiration as they still usd it when ever they saw any thing new; also Cherr, tut tut tut tut tut, which probably have the same signification. Their Canoe was not above 10 feet long and very narrow built, with an outrigger fitted much like those at the Islands only far inferior; they in shallow waters set her on with poles, in deep paddled her with paddles about 4 feet long; she just carried 4 people so that the 6 who visited us today were obligd to make 2 embarkations. Their Lances were much like those we had seen in Botany bay, only they were all of them single pointed, and some pointed with the stings of sting-rays and bearded with two or three beards of the same, which made them indeed a terrible weapon; the board or stick with which they flung them was also made in a neater manner. After having staid with us the greatest part of the morning they went away as they came. While they staid 2 more and a young woman made their appearance upon the Beach; she was to the utmost that we could see with our glasses as naked as the men.

...about this time 5 of the natives came over and stay'd with us all the forenoon there were 7 in the whole 5 Men a woman and a boy, these two last stay'd on the point of sand on the other side of the

harbourRiver about 200 Yards from us, we could very clearly see with our glasses that the woman was as naked as ever she was born even those parts which I allways before now thought Nature would have taught a woman to conceal were uncover'd.

No mention is made by Cook or Banks of contact and communication with the natives for the next five days, but on July 17 Banks writes the following:

Tupia who was over the water by himself saw 3 Indians, who gave him a kind of longish roots about as thick as a mans finger and of a very good taste. On his return the Captn Dr Solander and myself went over in hopes to see them and renew our connections; we met with four in a canoe who soon after came ashore and came to us without any signs of fear. After receiving the beads etc. that we had given them they went away; we attempted to follow them hoping that they would lead us to their fellows where we might have an opportunity of seeing their Women; they however by signs made us understand that they did not desire our company.

The lack of fear, and increasing familiarity in interactions between the natives and the Europeans was also reflected in Cook's journal the following day:

Mr. Banks, Dr. Solander, and myself took a turn into the woods on the other side of the water, where we met with 5 of the Natives; and although we had not seen any of them before, they came to us without showing any signs of fear. 2 of these wore Necklaces made of Shells, which they seem'd to Value, as they would not part with them.

While the natives had not shown any interest in offerings of trinkets or items valued by Europeans, such as mirrors and cloth, the presence of freshly hunted turtles aboard the Endeavour piqued their interest.

...we return'd to the Ship without meeting with anything remarkable, and found several of the Natives on board. At this time we had 12 tortoise or Turtle upon our Decks, which they took more Notice of than anything Else in the Ship, as I was told by the officers, for their Curiosity was Satisfied before I got on board, and they went away soon after.

And Banks recorded of the day's interactions:

Indians were over with us today and seemd to have lost all fear of us and became quite familiar; one of them at our desire threw his Lance which was about 8 feet in Lengh--it flew with a degree of swiftness and steadyness that realy surprizd me, never being above 4 feet from the ground and stuck deep in at the distance of 50 paces. After this they venturd on board the ship and soon became our very good freinds, so the Captn and me left them to the care of those who staid on board and went to a high hill about Six miles from the ship;

On Thursday, July 19, the first dispute arises between the natives and the European visitors. The crew of the endeavour had been hunting sea turtles, whose meat was praised much by Joseph Banks in his diary. There were 8 or 9 large turtles on the deck of the Endeavour when a party of 10 or 11 natives came aboard the ship that day:

Ten Indians visited us today and brought with them a larger quantity of Lances than they had ever done before, these they laid up in a tree leaving a man and a boy to take care of them and came on board the ship. They soon let us know their errand which was by some means or other to get one of our Turtle of which we had 8 or 9 laying upon the decks.

They first by signs askd for One and on being refusd shewd great marks of Resentment; one who had askd me on my refusal stamping with his foot pushd me from him with a countenance full of disdain and applyd to some one else; as however they met with no encouragement in this they laid hold of a turtle and hauld him forwards towards the side of the ship where their canoe lay. It however was soon taken from them and replacd. They nevertheless repeated the expiriment 2 or 3 times and after meeting with so many repulses all in an instant leapd into their Canoe and went ashore where I had got before them Just ready to set out plant gathering; they seizd their arms in an instant, and taking fire from under a pitch kettle which was boiling they began to set fire to the grass to windward of the few things we had left ashore with surprizing dexterity and quickness; the grass which was 4 or 5 feet high and as dry as stubble burnt with vast fury.

A Tent of mine which had been put up for Tupia when he was sick was the only thing of any consequence in the way of it so I leapd into a boat to fetch some people from the ship in order to save it, and quickly returning hauld it down to the beach Just time enough. The Captn in the meantime followd the Indians to prevent their burning our Linnen and the Seine which lay on the grass just where they were gone. He had no musquet with him so soon returnd to fetch one for no threats or signs would make them desist. Mine was ashore and another loaded with shot, so we ran as fast as possible towards them and came just time enough to save the Seine by firing at an Indian who had already fird the grass in two places just to windward of it; on the shot striking him, tho he was full 40 yards from the Captn who fird, he dropd his fire and ran nimbly to his comrades who all ran off pretty fast. The Captn then loaded his musquet with a ball and fird it into the Mangroves abreast of where they ran to shew them that they were not yet out of our reach, they ran on quickning their pace on hearing the Ball and we soon lost sight of them; we then returnd to the Seine where the people who were ashore had got the fire under.

We now thought we were free'd from these troublesome people but we soon heard their voices returning on which, anxious for some people who were washing that way, we ran towards them; on seeing us come with our musquets they again retird leasurely after an old man had venturd quite to us and said something which we could not understand. We followd for near a mile, then meeting with some rocks from whence we might observe their motions we sat down and they did so too about 100 yards from us. The little old man now came forward to us carrying in his hand a lance without a point. He halted several times and as he stood employd himself in collecting the moisture from under his arm pit with his finger which he every time drew through his mouth.

We beckond to him to come: he then spoke to the others who all laid their lances against a tree and leaving them came forwards likewise and soon came quite to us. They had with them it seems 3 strangers who wanted to see the ship but the man who was shot at and the boy were gone, so our troop now consisted of 11. The Strangers were presented to us by name and we gave them such trinkets as we had about us; then we all proceeded towards the ship, they making signs as they came along that they would not set fire to the grass again and we distributing musquet balls among them and by our signs explaining their effect. When they came abreast of the ship they sat down but could not be prevaild upon to come on board, so after a little time we left them to their contemplations; they stayd about two hours and then departed.

The natives who visited July 19 were obviously insulted by the Europeans' refusal to hand over one or two of the turtles, but the incident did not lead to further conflict.

Cook was ready to go to sea but was delayed for several days by unfavorable winds. On July 23 Cook recorded the following incident in his journal:

Fresh breezes in the South-East quarter, which so long as it continues will confine us in Port. Yesterday, A.M., I sent some people in the Country to gather greens, one of which stragled from the rest, and met with 4 of the Natives by a fire, on which they were broiling a Fowl, and the hind leg of one of the Animals before spoke of. He had the presence of mind not to run from them (being unarm'd), least they should pursue him, but went and set down by them; and after he had set a little while, and they had felt his hands and other parts of his body, they suffer'd him to go away without offering the least insult, and perceiving that he did not go right for the Ship they directed him which way to go.

In the meanwhile, while "out botanizing," Banks realized the lack of value the natives put on the alien commodities proferred to them by the Europeans:

In Botanizing today on the other side of the river we accidentaly found the greatest part of the clothes which had been given to the Indians left all in a heap together, doubtless as lumber not worth carriage. May be had we lookd farther we should have found our other trinkets, for they seemd to set no value upon any thing we had except our turtle, which of all things we were the least able to spare them.

By July 1, repairs to the ship were completed, and Cook's attention had turned to the journey home.

The ship was now finishd and tomorrow being the highest spring tide it was intended to haul her off, so we began to think how we should get out of this place, where so lately to get only in was our utmost ambition. We had observ'd in coming in innumerable shoals and sands all round us so we went upon a high hill to see what passage to the sea might be open. When we came there the Prospect was indeed melancholy: the sea every where full of innumerable shoals, some above and some under water, and no prospect of any streight passage out. To return as we came was impossible, the trade wind blew directly in our teeth; most dangerous then our navigation must be among unknown dangers. How soon might we again be reducd to the misfortune we had so lately escapd! Escapd indeed we had not till we were again in an open sea.

It is interesting to note that these historically significant events - the first contact between Europeans and the natives of Australia, and the first description and naming of the Kangaroo; occurred after the Europeans were ready to depart, as they would have happily done if they were able to find a safe passage through the treacherous Great Barrier Reef.

Having failed to discover a safe passage, and winds turning slightly in their favor, the Endeaver finally unmoored from the river harbor that had been home for the last two months on August 4, 1770. It took 10 days for Cook to navigate gingerly through the reefs to the open sea. Banks relief to be away from the land was palpable:

For the first time these three months we were this day out of sight of Land to our no small satisfaction: that very Ocean which had formerly been look'd upon with terror by (maybe) all of us was now the Assylum we had long wishd for and at last found. Satisfaction was clearly painted in every mans face:

The native people of the Endeavour River, having witnessed the arrival and 6-week-long stay of the Europeans, would go back to their traditional way of life, undisturbed by such strange visitors until the Palmer River gold rush of 1873.