The most notable features of Cape River society are patience, patchwork, rags, resignation, Chinamen, and fleas.1

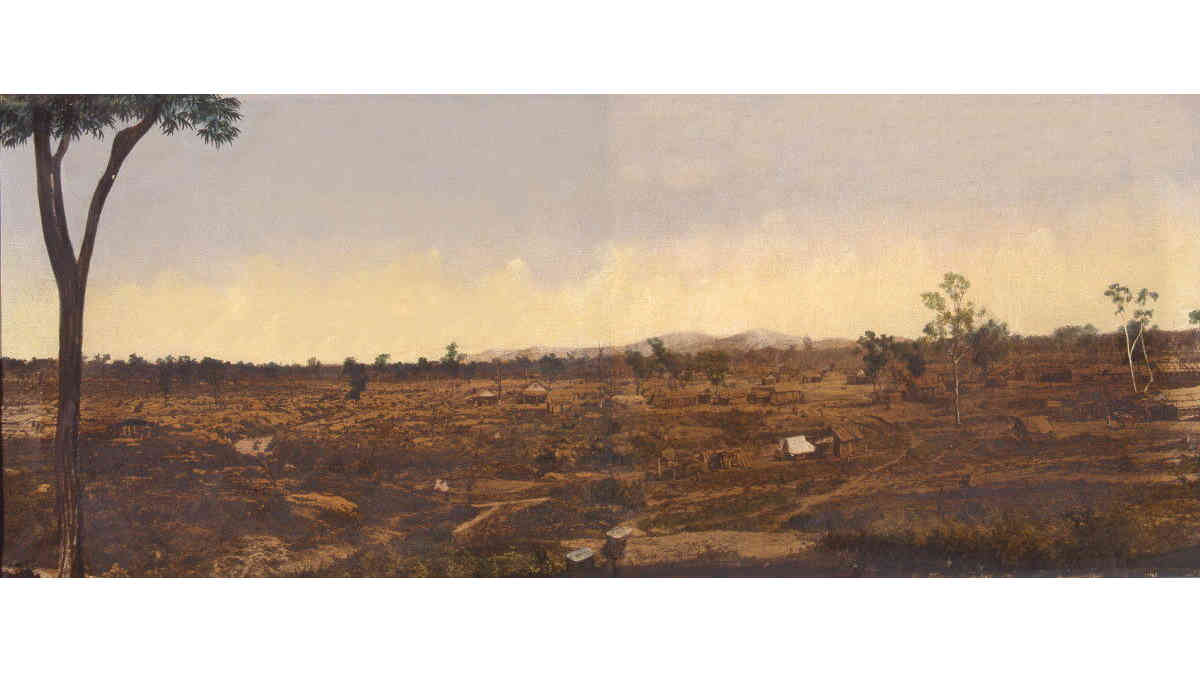

In July, 1867, a party of six prospectors reported finding gold on the upper reaches of the Cape River, about 130 miles west of Townsville. By the following month there were 250 diggers on the field, and by October, 600.2 The population of the Cape River gold field peaked the following year at around 2,500 people.3 By the end of 1868, there were only 500 Europeans and several hundred Chinese on the field,4 and in 1871 there were just 317 people: 156 Europeans and 161 Chinese.5

Cape River was the first gold field in north Queensland, and set a pattern for the many that were to follow, some just as short-lived, and some that were to have longer term economic sustainability.

Discovery

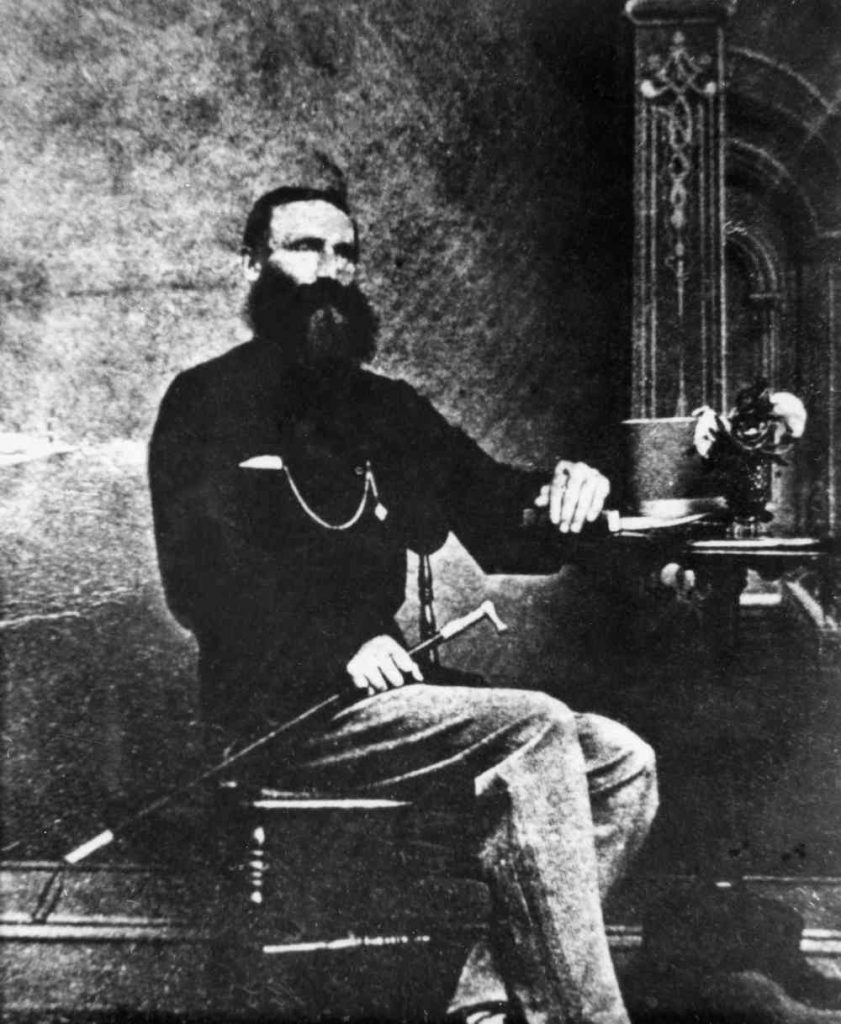

Richard Daintree had identified the Cape River area as auriferous (gold bearing) as early as 18636, and made a formal report to the Queensland Government about the district’s potential in 1865. It was on Daintree’s advice that the first prospectors – David James, Robert Robinson, Thomas Ellem, Charles Chappel, James Hewson, and James Stoner, found gold at Cape River In 18677, and it was Daintree who wrote to the government on those prospector’s behalf, to submit their application for a reward for finding “payable gold.”

In an accompanying letter that was published in The Brisbane Courier, Daintree warned potential prospectors of the difficulties they may face on the remote field, recommending only those with capital should attempt to work there:

At the same time I would warn intending miners that at present water is very scarce, and a sudden pressure of population (especially of those who could not afford to pile their wash dirt until the rainy season), would lead to disappointment.8

As well as alluvial gold, quartz reefs were found, and in December it was reported that a lump of quartz weighing over 20 pounds had been broken up and “gold was found through every piece of it.” Men were arriving daily from surrounding districts, but there was still no water. Some alluvial miners were using a method of “dry washing” and finding payable gold, while others paid teamsters to cart wash-dirt to water.9

Rivalry between Townsville and Bowen

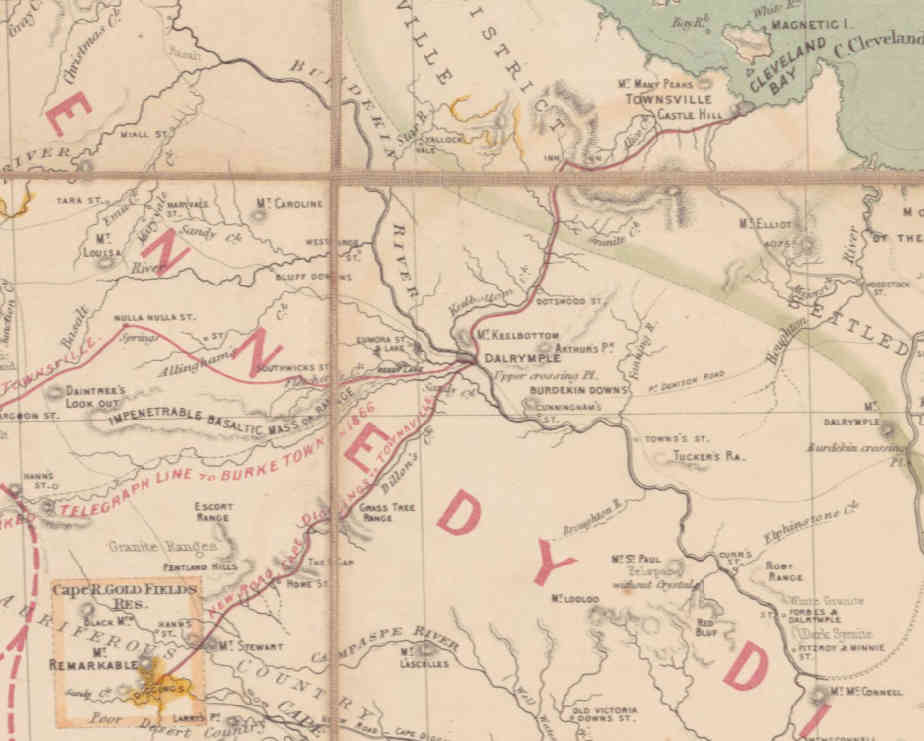

A pattern that was to repeat itself in north Queensland was the rivalry between coastal towns to be the main port for inland mining district. Townsville was closer to the Cape Diggings by more than 100 miles, yet Bowen was on the same side of the Burdekin River, had no mountain range to cross, and had a better port.

Already rivals for the commerce of the inland pastoral industry, as soon as the rush to the Cape River began, the race was on to mark a road from each port, and to provide gold escort and mail services. On August 1, a gold escort departed Bowen, and the following day the Townsville Volunteer Gold Escort set off for the Cape River. It is not surprising that the Townsville party arrived first, but to their surprise, just seven hours later, an avant courier from the Bowen party arrived and informed the diggers that if they were to wait for the arrival of the Bowen Gold Escort, they could fetch £3 16s per ounce of gold. Townsville was offering £3 12s. As a result, the Bowen escort returned with 300 ounces, while Townsville only acquired 120 ounces.10

Improvements to the road from Townsville, reduced the distance to 150 miles, and in November, the Townsville Volunteer Gold Escort took only three days to reach the Cape Diggings. The road carried traffic of drays loaded with supplies for the gold field, and it was recommended a public house be set up midway on Emu Creek as the number of travelers met along the road was “very considerable.”11

Proponents for Bowen cited that her port was superior, and that the track from Townsville, while shorter, required crossing the Burdekin River and climbing over a range, but in the end miners voted with their feet.

The diggings may be reached either by way of Bowen or Cleveland Bay [Townsville], but for those who have to walk there is a great difference in the length of the road; via Bowen it is called 285 miles, but 310 is nearer the mark, and a rough road it is; via Cleveland Bay the distance is called 150 miles – in fact a man can go and return to Cleveland Bay in the same time that it would take him to go from Bowen.11

Law and Disorder

Such a remote gold field had a tendency to attract mostly single men, willing to take a gamble in the hope of striking it rich, and tough enough to endure hardship. Some of these men showed little respect for the law when the law eventually arrived on the gold field in November, 1867.

Mr. Chartres[sic], the recently-appointed commissioner, reached here on the 2nd instant, accompanied by two troopers. The day after he arrived some man took a fancy to his horse and made off with it; he was pursued by one of the troopers, who recovered the horse, but the thief got clear off.12

No doubt, William Charter’s horse was a strong one, as Charters stood six-feet-four and-a-half-inch tall, and weighed nineteen stone, according to his subordinate Police Magistrate, W.R.O. Hill, who weighing in at just nine stone, carried Charters 150 yards on his shoulders to win a bet on a sports day.13

Serving as both Gold Commissioner and Police Magistrate, William Skelton Ewbank Melbourne Charters Esquire lived in a house on a little hill overlooking a rough and tumble town of canvas tents and bark huts.

Robert Gray, a pastoralist who had served as a British Army officer in India, and was familiar with the ways of the Raj, described Charters thus:

He was a big heavy man and used to go his rounds on a big grey horse. He wore a long gold watch chain around his neck, and in hot weather generally rode with an umbrella. An orderly followed him at a respectful distance. His appearance generally reminded one of an oriental magnate.14

Cape River may have been short of water, but it was never short of booze nor the violence that it fueled.

The Cape in 1868 was a decidedly rough locality, there being fully two thousand five hundred men, representing many nationalities, and among them the scum of all the Southern Gold Fields.

The police included eight constables under Senior-Sergeant Francis, a force totally insufficient to keep even a resemblance of law and order.

Gold was easily obtained and much more easily spent. Dreadful stuff, called whisky, rum and brandy, was sold in shilling drinks, and there was no need to wonder that many poor fellows, after the usual spree, became raving maniacs.

Picture in your imagination a mob of two hundred or three hundred half drunk semi-madmen running amok with each other in the brutal fights which were a daily occurrence!

I have seen a man kicked to death in the open daylight, the police and everybody else powerless to interfere.15

In 1868, there were more than 2,000 miners on the Cape River gold field. Returns from alluvial gold had become patchy, but reef gold was being mined from hard rock. In early October the newspapers reported that miners on the field were in possession of 10,000 ounces of gold, and were impatient for the gold escort from Bowen to arrive. There were between 80 and 90 licensed businesses in the town. Richard Daintree, the original discoverer, and now in the capacity of Government Geologist for Northern Queensland, had just paid a visit, reporting: “Some very rich quartz has been found on the Upper Cape during the last week, and 15 pounds of gold taken out of one small stone.”16

The reason gold was piling up appears to be caused by the hitherto volunteer gold escorts stopping after a highway robbery occurred on the road to Townsville in August, 1868.

On Saturday last, August 22, [Cleveland Bay Express] received information from the Cape River Diggings, that a Chinese storekeeper, on his way to this port, had been stuck up and robbed, of a sum of about £360, in gold and notes, besides two silver watches, by a party of bushrangers, consisting of three men, who had disguised themselves by blackening their faces.17

While the culprits were quickly tracked down and rounded up by the Cape River police, the ad hoc volunteer gold escorts that had first taken charge of a few hundred ounces of gold per trip, were not up to the task of carrying thousands of ounces.

The effect this sticking-up case will have on the receipt of gold by the banks in this town and also by our merchants and storekeepers, will be severely felt, until the Gold Escort is in working order. Great complaints are made by the diggers, at the delay in the establishing of this corps. At present none of the bankers will visit the diggings with a view to purchasing gold: ergo the diggers are obliged to keep it themselves, as no one cares to risk escorting large amounts to town.18

When the Government gold escort finally came, miners complained that it had been entrusted to black troopers, who, according to a correspondent, “are not to be trusted in case the escort was stuck-up.”19

Horse thieves remained rampant on the Cape River along with sly grog shops and general lawlessness.

As yet, no man could ever turn a horse out without losing hobbles, bell, and in all probability, horse and all – which, strange to say, would always turn up a day or two after a reward was offered.20

In January, 1869, a disgruntled miner and resident of the Cape River township wrote a letter to the editor complaining about the behavior of the police and of his treatment by Magistrate Charters. Joseph Leader claims to have been assaulted by an intoxicated police sergeant, only to have the case dismissed due to Sergeant Lang having been too intoxicated to recall the incident, and because, according to Charters, Leader had showed up five minutes late for the hearing. Leader was also charged 20s in costs.

I and my witnesses were five minutes too late. Now, Sir, not being blessed with a town clock, nor any indication of Saturn’s rapid strides, we miners are compelled to take Sol for our timekeeper. How do we know that Mr. Charters is the happy possessor of the correct time of day? If such is the case, why does he not place it in some conspicuous place so that we may all know how man’s greatest enemy is progressing?21

The regular correspondent to The Queenslander cited Leader’s case as but one example of “the usual miscarriage of justice, which is now getting proverbial in this part.”22

Lack of faith in the ability of the police to maintain the law, and the fairness of “justice ” that was meted out by Magistrate Charters continued through 1869, with the correspondent writing in April:

We have had a series of clever captures and disgraceful escapes of some noted scoundrels the details of which I think worth giving you, as showing what kind of police management we have up here … Some time ago, a well known character called “Long Sam,” or “The Grasshopper,” and for whose apprehension there are no less than four warrants for horse-stealing, &c. – and it is reported that he has taken as many as sixteen horses at one time from off these diggings alone – was flitting about and visiting a friend’s house not half a mile from the Police Camp. Two constables, in disguise, proceeded to the locality one night, and happened to stumble almost upon their man, who was lying asleep in a gully, rolled up in a blanket, with a loaded revolver resting on his chest. He was secured, and sent down to the lock-up at the Lower Cape, and from which (in company with another person for forgery) he made his escape the other night…

At the time all this was doing there were three constables and the sub-inspector sleeping under the same roof, and a man on guard. Now, for gross negligence, I think this beats all I ever heard of. It puts one in mind of a lot of schoolboys “playing at police,” catching their prisoners, and then letting them go just for the fund of catching them again.23

The lock-up from which the men escaped was a mere log structure, with no iron bars. A new, more secure lock-up was completed in October.

The new lock-up, which has been so very badly wanted, will be ready for the reception of inmates by the end of the week, when, I have no doubt, some unoffending person will be thrust in just by way of trying how it suits.24

In November, 1869, the newspaper correspondent expressed the hope that the arrival of Sub-Inspector Balfrey from Rockhampton and Clermont would bring changes to a police force that had fallen into disrepute.

Mr. Sub-Inspector Balfrey arrived here from Clermont during the week, and commences his duties forthwith. Hitherto this station has been badly worked, and the escape of several prisoners has thrown great discredit upon the police … we hope to have heard the last of the complaints here, and that there soon will be a perceptible change for the better, and the career of the horse-tailers and shanty-keepers will soon be brought to an end.18

Rush to the Gilbert River

After peaking in population in 1868, in mid 1869, numbers were rapidly declining with a new gold field being discovered in the Gilbert Ranges around 250 miles northwest of the Cape River Diggings.

The Gilbert still continues the great centre of attraction, and the population here is getting ‘smaller by degrees, and beautifully less.’ Six weeks ago, and from my tent, I could count dozens of bright camp fires dotting the river bank and the ridge beyond, and hear the merry laugh responding to some quaint joke or story told by some old digger to his circle of mates and friends as they sat smoking ‘the calumet of peace.’ But now, all is darkness, and the silence is only broken by the barking or howling of the numerous mongrels which abound here.25

As the miners left, the storekeepers followed:

Half the storekeepers are leaving the Cape for the Gilbert. Drays are constantly loading, and we shall soon have no greater number of stores than are requisite. Lately it has been overdone; sufficient stores have been sent from Townsville for a population of 10,000 instead of our 3,000 and odd, and consequently storekeepers have had stores on hand for twelve months and more.26

According to Police Sub-Inspector Clohesy, in the first 10 days of May, at least one thousand miners left Cape River for the Gilbert.27

It wasn’t the end for the Cape River Diggings, it merely reduced the population of miners and businessmen to a more sustainable level, and the town became a stopping point on the road to gold fields further north. The Townsville gold escort now travelled to the Gilbert, picked up the gold and mail there, then stopped at Cape River to do the same. In October, 1869, the escort loaded 1,670 ounces of gold at the Gilbert, and 1,341 ounces at Cape River, making “a very good parcel for shipment by the next boat.”27 And also in October, the Government Gazette announced the sale of town lots, marking the establishment of an official township, although it was not clear at first what the name of the town would be: “Some say it is ‘Daintree,’ others ‘Capeville,’ but nobody really knows.”28 In the end it was to be Capeville.

The Chinese

By February 1869, Cape River had its own “China Town,” and the Chinese outnumbered the Europeans by more than two to one, with about seven hundred Europeans, and fifteen hundred Celestials on the Cape diggings, according to one correspondent.29

The Chinamen have a very neat little township all to themselves, and certainly deserve their meed of praise for the systematic way they have laid it out, and, judging from the substantial appearance of their hotels and stores, they have evidently made up their minds to become permanent residents.30

The presence of a large number of Chinese was viewed by some in a negative light:

As I understand that the rage for cheap labor is the cause of so many Chinese being in this country – in passing through that part of the diggings known as China Town, I noticed many of the offspring of Chinamen and white women, and I am prejudiced enough to believe that our own race would be far superior to a mongrel breed of Chinese coolies and South Sea Islanders.1

But some viewed the tropics are less suitable for Europeans, and appreciated the hardworking thrift of the Chinese:

The Chinese are the men for the North of Queensland, they being acclimatised, and their habits suit them in every way for settling in that part of the country… They have proved what they can do in the way of mining by their stay on the Cape River, for they have contributed a very large share towards the last escort, and always appear to have more energy in working for “tucker” only than an European could muster in this hot climate.31

The proportion of Chinese to Europeans increased even further when the rush to the Gilbert River began in April/May 1869. Probably due to resentment at the large numbers of Chinese already at Cape River, the European miners immediately decided that the Chinese were not to be allowed on the Gilbert. Writing from Cape River, Sub-Inspector Clohesy reported:

There is a general clearing out of all diggers, except Chinamen, and they will not be let on the Gilbert ground. Last week six Chinamen returned and reported to me that they were beaten and kicked off the ground, their horses and rations taken from them, and had to walk from there here to save their lives.32

Clohesy reported that there were around 1,200 men on the Gilbert, and in Cape River about 1,000 Europeans and 1,200 Chinese.

In 1870, the Chinese appear to have successfully gained a foothold at the Gilbert, and the Cape River correspondent reported that the Chinese were heading to the Gilbert daily in their dozens.

By 1870, the glory days of the Cape River were over. Remaining miners hoped for new discoveries that could revive the peak of prosperity, but by August it was reported that “there are very few men here, and the township itself -vis, Capeville – looks like a graveyard, with empty houses as mementos of departed glories.”33

- “Cape River: From a Correspondent,” The Queenslander, Saturday, November 6, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20326447 ↩︎

- A Thousand Miles Away: a history of North Queensland to 1920, G. C. Bolton, Australian National University Press,1970 ↩︎

- A place not very much better than Hades: archaeological landscapes of the Cape River gold field, North Queensland, John Brian Edgar, PhD thesis, James Cook University, 2014 https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/43169/ ↩︎

- Archaeological Evaluation of Pentland Historical Cemetery, Queensland, Australia, Markus Zuercher, 2016. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316959729_Archaeological_Evaluation_of_Pentland_Historical_Cemetery_Queensland_Australia ↩︎

- QLD. Statistics of the Colony of Queensland, 1871, Registrar General (Qld), Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1872. ↩︎

- In the letter Daintree wrote to the government in 1867, cited in “Cape River Gold-Fields,” The Brisbane Courier, Tuesday, August 6, 1867., Daintree mentioned that: “Four years ago, in a paper read before the Royal Society of Victoria, and published in the Yeoman, I indicated in general terms the auriferous character of this district.”https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1286367 ↩︎

- Bolton, 1970 ↩︎

- “Cape River Gold-Fields,” The Brisbane Courier, Tuesday, August 6, 1867. ↩︎

- “Cape River Gold Fields,” Warwick Examiner and Times, Saturday, December 14, 1867. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/82095904 ↩︎

- “Cleveland Bay (From the Express),” Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, Tuesday, September 3, 1867. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/123610334 ↩︎

- “Cape River Gold Field,” The Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser, Tuesday, November 12, 1867. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/75518842 ↩︎

- “The Cape River Gold-Fields,” The Queenslander, Saturday, November 9, 1867. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20315947 ↩︎

- ↩︎

- ↩︎

- Forty-five years’ experiences in north Queensland, 1861 to 1905 : with a few incidents in England 1844 to 1861, W.R.O. Hill, H. Pole & Co., Printers, Brisbane, 1907. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:216455 ↩︎

- “Cape River,” Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, Tuesday, October 6, 1868. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/123356030 ↩︎

- “Cape River,” The Queenslander, Saturday, September 12, 1868. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20320450 ↩︎

- “Cape River,” Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, Saturday, September 26, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/148013119 ↩︎

- “Cape River Diggings: From a Correspondent,” The Queenslander, Saturday, January 23, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20322544 ↩︎

- “Cape River Gold-Field: From our own Correspondent,” The Brisbane Courier, Wednesday, December 1, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1303039 ↩︎

- “Cape River Justice,” The Queenslander, Saturday, February 13, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20322835 ↩︎

- “The Cape River (From our own Correspondent),” The Queenslander, Saturday, February 6, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20322789 ↩︎

- “Cape River Gold Field: From our own Correspondent,” The Queenslander, Saturday, May 1, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20323989 ↩︎

- “Cape River: From our Correspondent,” The Queenslander, Saturday, October 16, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20326152 ↩︎

- “The Cape River,” The Queenslander, Saturday, July 3, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20324831 ↩︎

- “The Gilbert and Cape River Goldfields,” Dalby Herald and Western Queensland Advertiser, Saturday, June 19, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/215450697 ↩︎

- “Report from Sub-Inspector Clohesy, Cape River, Respecting Rush to the Gilbert River,” The Brisbane Courier, Saturday, June 5, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1329047 ↩︎

- “Cape River: From our own Correspondent,” The Queenslander, Saturday, November 20, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20326596 ↩︎

- “The Cape River Diggings,” Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette, Thursday, February 4, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/168607080 ↩︎

- “Cape River Diggings,” Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette, Thursday, January 28, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/168607023 ↩︎

- “Cape River: From our own Correspondent,” The Queenslander, Saturday, October 16, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/20326152 ↩︎

- “Report from Sub-Inspector Clohesy, Cape River, Respecting Rush to the Gilbert River,” The Brisbane Courier, Saturday, June 5, 1869. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1329047 ↩︎

- The Bulletin, Rockhampton, Tuesday, August 30, 1870. ↩︎