The first white permanent resident of north Queensland arrived at Cape Cleveland, near the present day city of Townsville in 1846, along with 6 other castaways from the shipwrecked vessel, Peruvian.

Of these seven people, three died not long after landing. The four remaining survivors: Captain George Pitkethly, his wife, a young apprentice named Wilson1, and James Morrill were adopted by the local aboriginal people.

The captain, Mrs Pitkethly, and Wilson were dead within two years of their rescue, but Morrill survived and lived with the aborigines for 17 years, until the frontier of European settlement reached the region in the early 1860s, and Morrill decided to return to European society.

Morrill’s story was recorded in a pamphlet by Edmund Gregory: Sketch of the Residence of James Morrill Among the Aboriginals of Northern Queensland for Seventeen Years, (Brisbane, 1866).

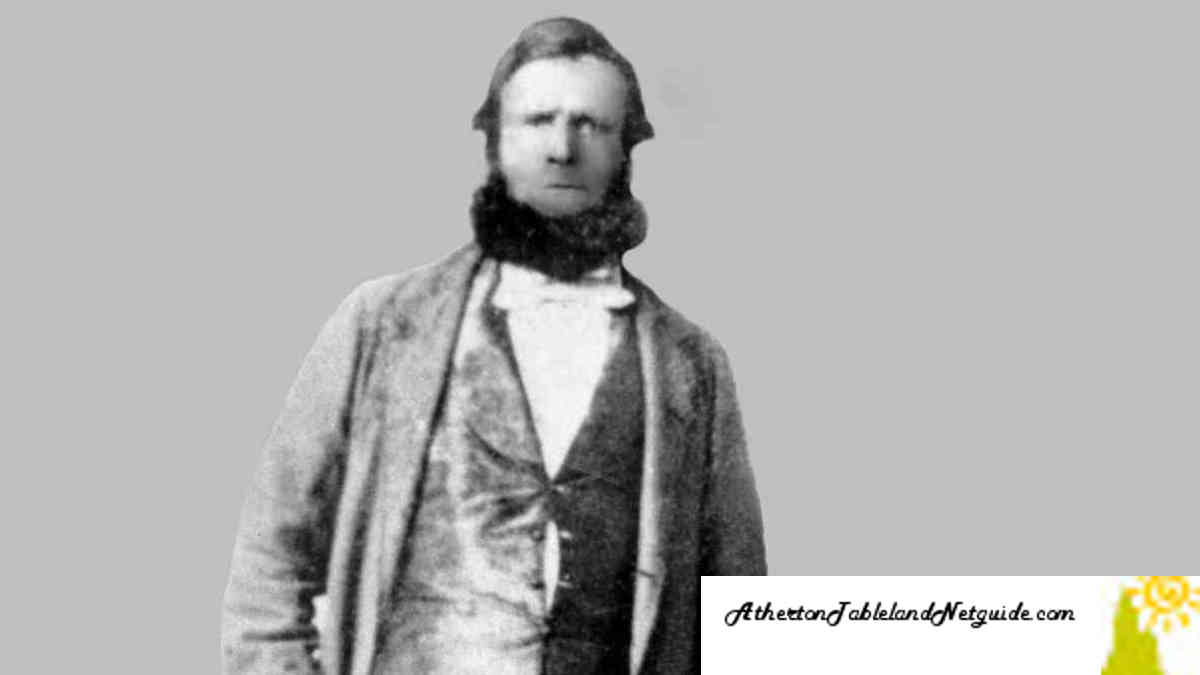

Morrill was born in the village of Heybridge, Essex, England May 20, 1824. He received a basic education until the age of 13 and was expected to work with his father, who was a millwright and engineer. However, against his parents wishes, Morrill went to sea as a sailor. At first he worked on smaller coastal vessels such as colliers, but apparently yearned for longer voyages, perhaps with a sense of adventure and desire to see the world.

In 1845, at the age of 21, Morrill joined the crew of the troop ship HMS Ramillies departing London for Hobart and Sydney. Not desiring to return to England yet, he then worked on the ship Terror, sailing to Auckland, New Zealand, then back to Sydney. On 24 of February, 1846, Morrill joined the crew of the Peruvian, about to set sail for China. The ill-fated ship, passengers, and crew, departed Sydney on February 27, and 9 days later, in the middle of the night, the Peruvian hit the Minerva Reef, in the Coral Sea, west of New Caledonia.

Twenty-one passengers and crew who survived the initial wreck boarded a hastily-built raft with only one small keg of water, a few tins of preserved meat, and a little brandy. According to Morrill, aboard the raft were “three ladies, two children, two gentlemen passengers, the captain, carpenter, sailmaker, cook, and four able seamen…four apprentices, and two black men stowaways, working their passage.”2

It. was agreed that the stores should be given out equally amongst us, and that there should be no lots drawn to take away each other’s lives. One tablespoonful of preserved meat a-day was served out, about 12 o’clock midday ; and the water was measured in the neck of a glass bottle, four to each person, one in the morning, two in the middle of the day, and the other in the evening.3

The castaways managed to catch birds, drinking their blood, and eating the flesh raw, but as they drew closer to land, birds stopped landing on or approaching the raft.

A few days after this the first death occurred, James Quarry, leaving his child to survive him but a very short time. He said the day before that he was dying, and that he should not live long. As soon as he died he was stripped and thrown over, the sharks devouring him instantly before our eyes.4

Fish were caught using a line and hook with a little piece of white rag as a lure, but just one per day, if they were lucky, to feed the 20 people aboard the raft.

Some rain was caught in a sail to replenish the meager supply. Two children, including a baby, died; followed shortly after by their mother.

As more people died, the fishing line was lost to a big fish. The castaways then used body parts of the dead to lure sharks, snaring them with a lassoed rope.

Forty-two days after abandoning the Peruvian, seven survivors reached the coast of Australia at Cape Cleveland. The survivors were in such a weakened state from starvation, dehydration, and “being so long aboard the raft without exercise it was difficult to move about at first,”5 they could barely make use of the fresh water and food, such as plentiful rock oysters, that were available.

Mr. Wilmott and James Gooley were so exhausted they were utterly unable to move about to provide for themselves ; so they laid down by a waterhole and died, nobody being equal to provide for more than their own absolute necessities.6

Jack Millar, the sailmaker, paddled away in aboriginal bark canoe found nearby. Morrill later learned from the aborigines that he had been found by them dead in the next bay, having apparently starved to death.

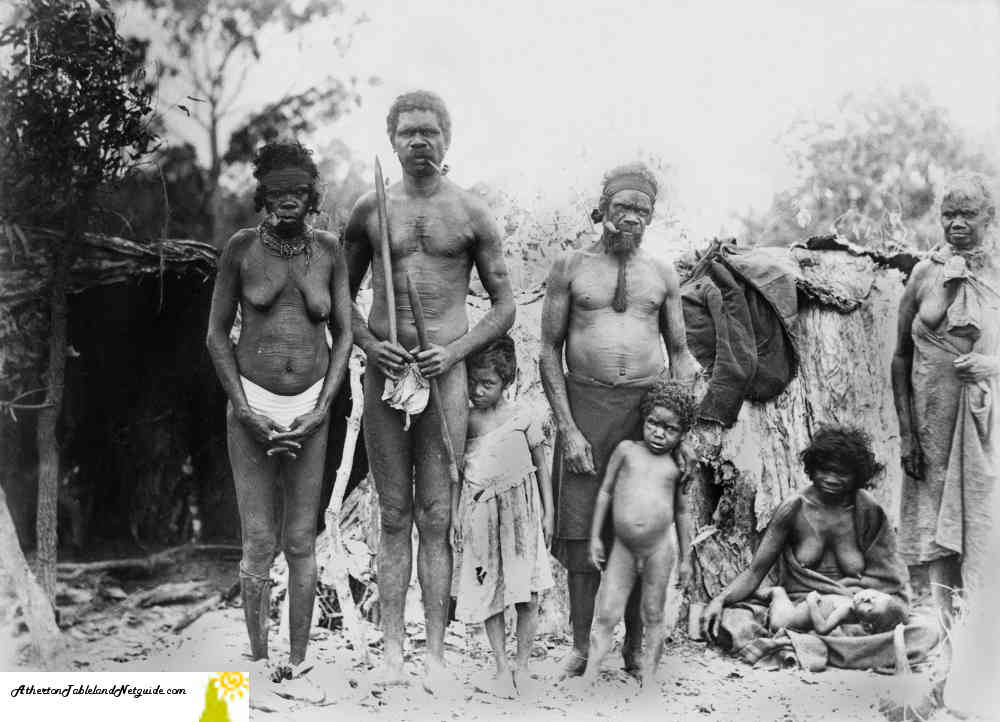

Around 14 days after landing, a group of around 30 aborigines arrived and made contact with the four surviving castaways. The emaciated and unarmed Europeans seemed to have not presented a threat to the natives, who camped with them overnight in the rock hollow in which the Europeans had been using as a shelter.

The aborigines offered food, and by gestures communicated there was more to be had inland if the castaways were to accompany them. Wilson, who was too weak to walk, was carried on the shoulders of one of the men “the same way as they carry their children when on a journey,”7 while the adults were assisted to walk the estimated eight miles inland to the main camp.

Before departure, the aborigines had made thorough physical examinations of the white people, probably to determine whether they were human or not, and to understand what actual differences there were between the strangers and themselves. The castaways were poked and prodded, including underneath their clothing in order to determine what sex they were.

As they journeyed inland, they several times met other aborigines, who likewise, made physical examinations. The castaways annoyance at being subjects to such intimate examinations, including of their private parts, was overridden by a greater fear “imagining that the examining and chattering blacks were excited by cannibal considerations.”8

The Europeans then became curiosities, exhibited by their aboriginal saviors by way of a spectacular performance. The natives hosted a corroberee, a kind of event which included theatrical displays of song, dance, and drama.

The first thing they did was to lay us down and cover us with dry grass, to prevent our being seen till an appointed time. They then collected from all quarters, to the number of about fifty or sixty—men, women, and children—and sat down in a circle ; those who discovered us stepped into the center, dressed up in our clothes, with a little extra paint, danced one of their dances, at the same time haranguing all present, recounting how they discovered us, in a rude sing-song tone, from whence they had brought us, and all they knew about us, all of which greatly surprised them : and then as a finale we were uncovered, and led forth into the center in triumph.9

The theatrical exhibition of the white castaways continued every evening for many days, with people from tribes ever further afield arriving as word spread around the district of the strange new arrivals.

The aboriginal hosts were generous to their stranded guests during this time, making sure they had plenty to eat and drink, and letting them rest in a gunyah while the aborigines went about the daily business of gathering food and sustenance. But the Europeans quickly tired of the evening performances of which they were the object of attention. Eventually the novelty of the white-skinned guests wore off, and as the Europeans recovered physically, they began to accompany the aborigines in daily tasks of survival and food gathering.

The Europeans learned to survive in the bush by finding edible roots, fishing, and snaring birds, which Morrill considered himself quite adept at:

I became very expert after awhile, even more so than the natives themselves, because I took more care in making strong string for the nooses, and in choosing the best places to set them ; also my sailor’s knowledge stood me in good stead in making running knots, which altogether tended to raise me in their estimation.10

Within five or six months, Morrill and the others could understand the language of the aborigines. The aborigines told Morrill about a large gathering of tribes that was to occur during the dry season in about four months time.

When the time came, Morrill witnessed the gathering of more than one thousand people, including tribes from far away to the South. The Europeans joined these southern tribes in the hope of getting closer to European settlement for better chance of getting back to civilization. Morrill went with one group who lived around today’s town of Bowen, while Wilson went with another even further south. Morrill does not specify where the captain and his wife went, but it is apparent that he was able to maintain personal contact with the couple, while only hearing news about Wilson by word of mouth.

About two years after we had been living with them intelligence was conveyed to us of the death of the lad, and that his remains had been burnt, as they did with their own dead.

About six weeks after the boy died the captain sickened and died also ; I believe the death of the boy, the degraded state of his wife, and the utter helplessness and hopelessness of saving her from her miseries preyed on his mind, so that he gave way to despair. Up to this time she managed with great difficulty to keep herself partially covered, but he knew it could not be for much longer ; and the thoughts of her being dragged down so low was too much for him—he sank under it.11

After the death of his compatriots, Morrill felt a sense of loneliness and alienation, and decided to go back to the tribe that had originally adopted him at Mount Elliot. Over the years, Morrill occasionally spotted a ship in the distance when he was fishing on the coast, or heard by word of mouth of ship landings, and European contact with the aboriginals. Sightings and contact with Europeans became more frequent as the years went by, and the frontier of European settlement crept steadily northwards.

Some of these contacts resulted in violent altercations. In one case, a ship’s crew landed at Cape Cleveland, shot one aboriginal man dead, and wounded another. Morrill worried that it may have been the enthusiasm of his aboriginal friends, in attempting to communicate to the white men of Morrill’s presence among them, that led to a misunderstanding, and caused the altercation.

In another case, Morrill received news that a man on horseback had shot at a group of aboriginals, killing one.

a report was brought to me by some members of a distant tribe that a white man had been seen with two horses, and that whilst some of a tribe were lamenting the death of an old man the white man fired in among them and shot the son, who fell dead across his father’s dead body.12

In retribution, the aborigines killed the white horseman.

One day, the blacks brought news to Morrill of strange, large creatures, seen wandering in their territory. When showed the tracks, Morrill realized they were the hoof marks of cattle. Morrill had mixed feelings about the coming of the white men: “the evident near approach of civilization greatly excited me and made me feel uneasy;” Morrill’s memoir recalls. Morrill at once realized the possibility of rescue and return to civilized life, but also realized the destruction that would inevitably result for the people he had lived among for 17 years.

Word came that members of the tribe he had lived with to the south had been shot by a large group of white and black men on horseback, and the frequency of sightings of white men, and cattle increased.

Morrill was constantly thinking about trying to make contact with the white settlers, but seems to have been torn at the idea of leaving the way of life he had become used to. He was even unsure of being able to communicate in English.

even if I met any of my own countrymen my long absence would prevent me making myself intelligible to them : for, certainly, I had long lost all likeness to a civilized being.13

When a fishing party of 15 men belonging to the tribe which had saved him were shot dead, Morrill decided that he must contact the white men to try to prevent the destruction of the tribe.

I then pressed them to let me go away and show me where the white men were that I might be the means of saving their lives. They reasoned among themselves that what I said was true, and accordingly they agreed to go on a hunting expedition with me on a hill called by the natives (Yamarama), which was about half-a-mile only from the out-station, which I was at last so soon to reach.14

Morrill observed a cabin at the outstation for a while, then washed himself in a waterhole “to make myself look as much like a white man as possible.”

Presently I got up on the fence to be free of the dogs, that they could not bite me, and called out as loud as possible, ” What cheer, mates ?” There were, it appeared, three persons living in the hut, but there were only two at home then. They heard me calling out, and knowing the voice to be strange, one of them came out and saw me on the fence : seeming to be neither black nor white and quite naked, he did not know what to make of me, he was awfully surprised ; he stepped back half in the hut again and called to his mate. ” Come out Bill, quick,” I understood him to say ; ” here is a red or a yellow man standing on the rails of the fence, naked—he is not a black man—bring the gun.” Being dreadfully afraid they would use it, I said “Do not shoot me, I am a British object—a British sailor.”15

Of course, Morrill meant British “subject” rather than “object,” but he hadn’t used the English language for 15 years, since his three companions had died. Morrill was surprised to learn that it was Sunday, 25th of January, 1863, and that he had been in company with the aborigines for a total of 17 years. It didn’t seem “half so long” to him.

Morrill attempted to be an intermediary between the aborigines and the white settlers, being given the message from the whites, that the aborigines would not be harmed if they did not interfere with the settlers, the white men also warned Morrill that if he did not return to them the next morning that they would put black trackers after he and his aboriginal companions, and that they would be shot.

Morrill conveyed the message, and after spending the night with the aborigines there was a sad scene of departure.

they asked me if I would come back in a few days. I told them no, I should probably be away three or four moons. They then said ” you will forget us altogether ;” and when I said good-bye, the man I was living with burst into tears, so did his gin, and several other gins and men. It was a wild touching scene. The remembrance of all their past kindnesses came up powerfully before, and quite overpowered, me. There was a short sharp struggle between a feeling of love I had for my old friends and companions, and the desire once more to live a civilized life…16

That day, Monday January 26, 1863, Morrill for the first time in more than 17 years, bathed with soap and a flannel, put on European clothes, and dined on mutton with a knife and fork.

Oh, for that supreme moment of my life, with knife and. fork in hand once more, and that salt and pepper, can I ever forget it !17

Just as Morrill had received attention as a curiosity by aborigines far and wide after being rescued at Cape Cleveland, Morrill now became a curiosity in the settler communities. In the tiny town of Bowen, he was provided with clothes, and money was collected on his behalf to help him on his way. He travelled to Rockhampton, and then on to Brisbane, in each place curious people gathered to see the man who had lived the life of “a wild black” among “the savages.” Some press articles referred to Morrill as “the wild white man.”

Having some difficulty in communicating in English at first, the shy Morrill was under constant pressure to tell his story and answer questions of public audiences.

Taken under the wing of a Baptist minister, Morrill gradually re-adapted to British society, made the acquaintance of such colonial luminaries as George Edmondstone, Member of the Legislative Assembly and Mayor of Brisbane, and was even introduced to the Queensland Governor, George Bowen. Morrill was appointed by the Executive Council as warehouse keeper at the Customs House at Bowen.

Despite his desire to be employed in a useful capacity, perhaps by the police, as a liaison between the aborigines and settlers in the Bowen district, Morrill is recorded as working as a messenger for the Customs Department at Port Denison (Bowen) in 1864.18

Morrill was aboard the Flora during a survey of Cleveland Bay in October 1864, and contributed many aboriginal names to landmarks and places named in that survey.19

Morrill acquired a little land, married and had a child. Occasionally in demand as an interpreter, Morrill was the go-to man for anybody who wanted information about the mysterious ways of the aborigines, whether a particular plant was poisonous or not, or information about the seasons and ecology of the area he had lived in long before the colonists arrived.

Plagued by painful rheumatic swellings he blamed on years of exposure when he lived in the wild, Morrill died on October 30, 1865, at the age of 41.

He was a general favourite throughout the district, and when his death became known in the town, the whole of the flags of the ships in harbour and at the various stores throughout the town were lowered to half-mast. His funeral was attended by a large number of mourners, including many of our influential citizens. The men belonging to the pilot-station had asked and obtained permission to act as bearers to their old comrade; the police also attended and moved in the procession next the hearse; then came the mayor, the police-magistrate, followed by a long string of vehicles, horsemen, and pedestrians.

During the reading of the solemn and beautiful service of the Church of England by the Rev. E. Griffiths many an eye glistened with the unbidden tears as some act of kindness of the departed was recalled.

James Morrill was by no means an old man, he being only forty-one, but he was rendered prematurely aged by the troubles and hardships he had encountered during his adventurous life. Could the Mount Elliott blacks learn that their pale-faced brother was dead, what howling and woe would there be! But their grief though perhaps more demonstrative, could not be more serious or more deeply felt than is that experienced by the people of Bowen at the loss of one who was always ready to explain the use of a blackfellow’s mysterious weapon, or the qualities, poisonous or otherwise, of the various roots and plants found in the neighbourhood.20

If you enjoyed this article, please consider tipping to the author the price of a coffee or beer:

Footnotes, sources and citations

- Throughout his memoir, Morrill never refers to Wilson by name, but as “the boy” or “the lad.” However, a correspondent from the Rockhampton Bulletin who interviewed Morrill within a month of his return to civilization recorded the name as part of the interview. The report was republished as “Particulars of the Escape of James Morrill, Sydney Mail, Saturday, March 21, 1863. ↩︎

- Narrative of James Murrells’ (“Jemmy Morrill”) Seventeen Years’ Exile Among the Wild Blacks of North Queensland and his Life and Shipwreck and Terrible Adventures Among Savage Tribes; Their Manners, Customs, Languages, and Superstitions; also Murrell’s Rescue and Return to Civilization,” E. Gregory, Brisbane, 1896 ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Particulars of the Escape of James Morrill,” op.cit. ↩︎

- E. Gregory, Op.cit. ↩︎

- E. Gregory, Op.cit. ↩︎

- E. Gregory, Op.cit. ↩︎

- E. Gregory, Op.cit. ↩︎

- E. Gregory, Op.cit. ↩︎

- E. Gregory, Op.cit. ↩︎

- E. Gregory, Op.cit. ↩︎

- E. Gregory, Op.cit. ↩︎

- E. Gregory, Op.cit. ↩︎

- Pugh’s Queensland almanac, directory and law calendar, 1864 ↩︎

- “Highways and Byways,” The Origin of Townsville Street Names, Compiled by John Mathew, Townsville Library Service, 1995. https://www.townsville.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/21059/Highways-and-Byways-Jan-2009-2.pdf ↩︎

- “Death of James Morrill,” Rockhampton Bulletin and Central Queensland Advertiser, Thursday, December 7, 1865 ↩︎