My first expedition with the blacks - A night in the forest - Fear of evil spirits - Morning toilet - Maja yarri - Borboby - The "lists" of the natives - Warriors in full dress - Swords and shields - Fights - The rights of black women - Abduction of women

The first black man recommended to me by Jacky was named Morbora. He belonged to a remote tribe on friendly terms with the blacks of Herbert River, and was regarded as an excellent hunter. Both he and his brother Mangoran declared themselves willing to accompany me. Morbora was a strong, muscular, square-built man hardly twenty years old, with a remarkably low forehead. He was unable to speak a word of English, and trembled with fear when Jacky introduced him to me. I did all in my power to quiet this young black, and took more than usual interest in him, though I soon noticed that he, like all his black brethren, sought to take advantage of my friendliness; still he was very useful to me.

Mangoran was lean and slender in comparison with his brother, and he looked more like a brute than a human being. His mouth was large, extending almost from one ear to the other. When he talked he rubbed his belly with complacency, as if the sight of me made his mouth water, and he gave me an impression that he would like to devour me on the spot. He always wore a smiling face, a mask behind which all the natives conceal their treacherous nature. Besides these two I secured a young lad, whom we called Pickle-bottle. He was to some extent "civilised," and had learned a few English words; the other two were myall.

When we set out we were joined by Mangoran's wife, a tolerably good-looking woman. The first night we encamped near a brook under a newly-fallen tree; we cut down some small trees, laid them sloping on both sides of the tree-trunk, and made a roof of grass.

Outside this cabin, of which I took possession, my blacks encamped in the shelter of some bushes which they had procured for the night, for the weather was very fine. I let the horses loose, tied bells on to their necks, and fetched some water in a big tin pail which I had brought with me on this trip to boil the meat in. A large fire was built, as we had to bake bread and needed plenty of ashes. After these preparations, and when I had been to the brook and taken my usual bath, I had to prepare supper. I sent one of the blacks to the nearest large gum-tree to chop off a piece of bark, on which, with the skill of a bushman, I kneaded the dough of wheat flour and water into the regular round cake. This damper was then baked in the ashes, while the beef was slowly boiling in the tin pail.

My companions were impatient for their supper, for the white man's food is a delicacy well-nigh equal to human flesh. I distributed beef and damper equally among them, but I noticed to my surprise that they all gave Mangoran a part of their share, Morbora being particularly generous. The cause of this generosity was not then clear to me; for Mangoran was a very poor hunter and not very strong, neither did he possess more than one wife, so that his authority could not rest on those qualifications, which usually carry influence among allied tribes. I afterwards learned that he was a cunning fellow, and was successful in procuring human flesh, and there is nothing else that ensures respect among the Australian aborigines in so high a degree. In regard to the relation between the two brothers, I afterwards discovered that Mangoran was simply a black Alphonse. Without much physical strength, and very lazy, he preferred to live in idleness, and he left it to his brother to furnish the menage a trois with the necessities of the day.

The food quickly disappeared into the greedy stomachs, and then they all called for tobacco (suttungo) and pipes (pipo). I gave them a piece each. They minced up the tobacco with their nails, rolled it between their hands, put into their pipes, and gave themselves up to the highest enjoyment.

The night was dark, but radiant with stars. The blacks were lying on their backs round the fire smoking their pipes, which now and then went out, for the tobacco was fresh and damp. The smoker rises a little, supports himself on his elbow, and tries to suck fire into his pipe again; then he lays himself down once more and revels in existence. But tobacco makes a man thirsty, especially if he spits a great deal, and now they want water, and their gestures and a few words indicate to me that they want to borrow my tin pail. One gets up and takes the pail, another plucks a handful of grass and twists it around a piece of dry wood or bark. This torch is lit, and a similar one is taken to light the way back. This is done, not so much to find the way, as for the reason that they are afraid to leave the camp in the dark. They are partly afraid of their devil, who is supposed to be prowling about at night, and partly they fear attacks from other tribes. All day long the native is cheerful and happy, but when the sun begins to set he becomes restless from the thoughts of the evil spirits of the night, and especially from remembering his strange neighbours, who may kill and eat him.

The blacks now kept quiet around the fire. All was still; not a sound was heard except the solitary melancholy bell which indicated where the horses were grazing. The natives usually lie on their backs when they sleep, and sometimes on their sides, but they never have anything under their heads, nor do they use any covering in the night. They therefore frequently waken from the cold, and then turn the other side to the fire. As a rule, they lie two or three huddled together in order to keep each other warm.

Early the next morning Morbora and I went out into the scrubs which covered a rocky hill close by. He thoroughly examined the trees, and looked carefully among the orchids and ferns, which grew as parasites far up the tree stems, for rats and pouched mice (Phascologale), and among the fallen leaves he searched for the rare yopolo (Hypsiprymnodon moschatus). According to the uniform custom of the natives when they ramble through the woods, he frequently took a handful of dirt or rubbish out of a crevice in the rock, or from a cleft in a tree, and smelt it to see if any animal had passed over it. The Australian has, upon the whole, a highly developed sense of smell. Of him the Scandinavian phrase is literally true, that he "sticks his finger in the ground and smells what land he is in." When he, for instance, digs a pouched mouse out of its hole, he now and then smells a handful of the earth to see whether the animal is at home or not. In this way he perceives whether he is approaching it. Although I know the smell peculiar to this animal, I was never able to discover it in the ground.

Morbora's skill in climbing trees was truly wonderful. He ascended them with about the same ease as we climb a flight of stairs, and everywhere all his senses were on the alert.

As there was no lawyer-palm near from which he could get a kamin to assist him in climbing, he had to manage in some other way. He broke a few branches from a little tree, made them all the same size, and laid them side by side, leaving the leaves on them. But as the branches were not so long as a kamin, he could not climb in the same manner as with the latter. The leaves furnished a hold and prevented his hands from slipping, thus compensating for the knot and greater length of the kamin; but in order to climb the tree he had to draw his heels right up to his body, which gave him a striking resemblance to a frog jumping up. If the tree was not too large in circumference, he simply embraced it with his arms without using the improvised kamin; he folded his hands and leaped up in the same curious attitude. If the tree leaned, it never occurred to him to climb with his knees as a white man would do, but he crawled up in the same manner as an ape would, on all fours, perfectly secure and well balanced.

Although the Australian natives are exceptionally skilful in climbing, still it would be an exaggeration to compare them in this respect to the apes. I also know white people in Australia who from childhood have practised climbing trees, and who have attained the same skill as the blacks.

After a day's march we came to a valley which extended to the summit of the Coast Mountains. We were to encamp near the foot of the mountain range, but the air in the bottom of the valley being surcharged with the fragrance of flowers, very hot, damp, and malarial, I determined to pitch our camp higher up, where the air was more pure, a thing utterly incomprehensible to the blacks. I followed my old rule and made my camp on high ground, to escape the miasma which produces fever and is found only in the bottoms. We had hard work to make our way up the slope in order to find a suitable place for encampment. It was dark before I released the horses, which disappeared in the tall grass.

As usual we awoke a little before sunrise; but it took the natives some time to rub the sleep out of their eyes. When a black is roused he does not at once recover his senses, and he needs more time than the uneducated whites to pull himself together. It was always difficult for my men to find their bearings in the morning, and they always had much to do before they were ready to begin the day. They lazily stretch and rub their limbs, and then sit down by the fire and light their pipes. When they at length are entirely awake they go to work and make a sort of toilet. They clean out their noses in a manner more peculiar than graceful. This morning I took particular notice of Morbora, who took a little round stick and put it up his nose horizontally, at the same time twirling it between his fingers, whereupon the contents disappeared in the same manner as among the apes in zoological gardens. The natives hardly ever wash themselves. In the heat of the summer, it is true, they throw themselves into every pool of water they come to, just like a dog; but this is done only in order to cool themselves, and not for the sake of cleanliness. In the winter, when it is cold, they never bathe. If they have soiled their hands with honey or blood they usually wipe them on the grass, or even sometimes wash them in their own water.

In the morning, or when they sit round the fire, they are usually occupied in pulling their beards and the hair from their bodies. It is also a common thing to see even the women take a fire-brand and scorch the hairs off. The hair on the head is never pulled out, but at rare intervals, when it grows too long, is burned off with a firebrand or cut away with a sharp clam-shell or a stone. When they come in contact with civilisation they generally use pieces of glass for this purpose, and I have even seen a black cut his hair off with a blunt axe which he had borrowed from a white man. This is all the care which their hair and beard receive, except that it is now and then freed from vermin, a feature of the toilet which must be regarded as a gastronomic enjoyment. The blacks are not troubled with fleas, but they are full of lice, which are rather large, of a dark colour, and quite different from the common Pediculus capitis; they frequently went astray and came into my quarters, but fortunately they did not there find the necessaries of life. Some of the natives are free from them, but the majority constantly betray their disagreeable presence by scratching their heads with both hands. These animals are also found upon the body, and their possessor may be constantly seen hunting them, an occupation which is at the same time a veritable enjoyment to him, for to speak plainly - he eats them. The blacks also practise this sport on each other for mutual gratification, and the operation is evidence of friendship and politeness.

Morbora and I again went out to look for yarri, and we followed the valley to the summit of the mountain range It was a difficult march, over large heaps of debris covered with carpets of creeping plants. Every now and then he would exclaim: "Now we will soon come to yarri!" for during the daytime the yarri sleeps in this sort of stony place, and Morbora examined with the greatest care every rocky cave in our path. He stated positively that we would find many yarri (Komorbory yarri) when we had ascended farther. But when we finally, with the greatest difficulty, had toiled our way to the summit, he proposed that we should go down again, saying, Maja yarri - that is. No yarri. The fact was that Morbora did not know the district. I became angry, and expressed my dissatisfaction in pretty strong terms, which made such an impression upon him that he showed a disposition to run away. The expression of his countenance and his whole manner were suddenly changed, and I was obliged to alter the tone of my voice at once. Had I spoken more angrily than I did, he doubtless would have disappeared and abandoned me to my fate.

Several times we saw some small black ants which lay their eggs in trees. Morbora struck the trunk of the tree with my tomahawk while I held my hands out below to receive them. Several handfuls came down, and I winnowed them in the same manner as my companion did - that is, by throwing them up in the air and at the same time blowing at them. In this manner the fragments of bark were separated from the eggs, which remained in my hands, and were refreshing and tasted like nuts.

When we returned to the camp we found the others lying round the fire waiting for something to eat. They had brought me nothing useful, as they were simply interested in filling their stomachs. The only things they had for me were some miserable remnants of honey and some white larvae, delicacies with which they had been gorging themselves all day. We removed our camp to another part of the valley, and made excursions in this region for a couple of days. But it soon appeared that Morbora, who was known as a skilful huntsman, could find nothing and was a stranger in this land, while the others cared only for my provisions and for eating honey and larvae, so I concluded that it would be a waste of time to stay here.

Mangoran, who was a great glutton, always smelt of honey, of which the natives are so fond that they can live on it exclusively for several days at a time. He was lazy and most unreliable, and simply a parasite whom I had to tolerate for the sake of his brother; he only did me harm by demoralising my other people. On one occasion Pickle-bottle stated that there were no boongary to be found here, but that in another "land" he had seen the marks of their claws on the tree-trunks as distinct as if they had been cut with a knife. This was another reason for my leaving as soon as possible. The main result of this, my first expedition, was therefore some valuable experience. I returned to the station and remained there a couple of days, preparing myself for a hew expedition to another "land," where the natives said that yarri and boongary were found in abundance.

A great borboby was to take place three miles from Herbert Vale. A borboby is a meeting for contest, where the blacks assemble from many "lands" in order to decide their disputes by combat. As I felt a desire to witness this assembly, I asked Jacky if I could accompany him and those who were going with him, and no objection was made.

In the afternoon we all started from Herbert Vale, I on horseback and taking my gun with me. We crossed Herbert River three times, and as we gradually approached the fighting ground we met more and more small tribes who had been lying the whole day in the cool scrubs along the river to gather strength for the impending conflict. All of them, even the women and the children, joined us, except a small company of the former who remained near the river. I learned that these women were not permitted to be present because they had menses. As far as I know, the Australians everywhere regard their women as unclean in such circumstances. In some parts of the continent they are isolated in huts by themselves, and no one will touch a dish which they use; among other tribes a woman in this condition is not permitted to walk over the net which the men are making.

All were in their best toilet, for when the blacks are to go to dance or to borboby they decorate themselves as best they can. The preparations take several days, spent in seeking earth colours and wax, which are kept by the most prominent members of the tribe until the day of the contest.

On the forenoon of the borboby day they remain in camp and do not go out hunting, for they are then occupied in decorating themselves. They rub themselves partially or wholly with the red or yellow earth paint; sometimes they besmear their whole body with a mixture of crushed charcoal and fat - as if they were not already black enough! As a rule, they do not mind whether the whole body is painted or not, if only the face has been thoroughly coloured.

Not only do the men but the women also, though in a less degree, paint grotesque figures of red earth and charcoal across their faces. But one of the most important considerations on these solemn occasions is the dressing of the hair. It is filled with beeswax, so that it stands out in large tufts, or at times it has the appearance of a single large cake. They also frequently stick feathers into it. The wax remains there for weeks, until it finally disappears from wear or bathing. This waxed headgear shines and glistens in the sun, and gives them a sort of "polished" exterior. Some of the most "civilised" natives may wear a shirt or a hat. On this occasion two of them were fortunate enough to own old shirts, two others had hats on their heads, while the variegated colour of the body was a substitute for the rest of their attire.

Jacky was the best dressed fellow of the lot. His suit consisted of a white and, strange to say, clean body of a dress that had previously belonged to a woman. How he had obtained it in this part of the country was a mystery to me. As he was stoutly built, this product of civilisation looked like a strait-waistcoat, and threatened every moment to burst in the back. He strutted about among his comrades majestically, with a sense of being far removed above the"myall" (the mob). Two of the natives distinguished themselves by being painted yellow over the whole body except the hair. This was thought to be a very imposing attire, especially calculated to inspire fear.

All the natives were armed. They had quantities of spears, whole bundles of nulla-nullas and boomerangs, besides their large wooden shields and wooden swords. The shield, which reaches to a man's hip and is about half as wide as it is long, is made of a kind of light fig-tree wood. It is oval, massive, and slightly convex. In the centre, on the front side, there is a sort of shield-boss, the inner side being nearly flat. When the native holds this shield in his left hand before him, the greater part of his body is protected. The front is painted in a grotesque and effective manner with red, white, and yellow earth colours, and is divided into fields which, wonderfully enough, differ in each man's shield, and thus constitute his coat of arms.

The wooden sword, the necessary companion of the shield, is about five inches wide up to the point, which is slightly rounded, and usually reaches from the foot to the shoulder. It is made of hard wood, with a short handle for only one hand, and is so heavy that any one not used to it can scarcely balance it perpendicularly with half-extended arm - the position always adopted before the battle begins.

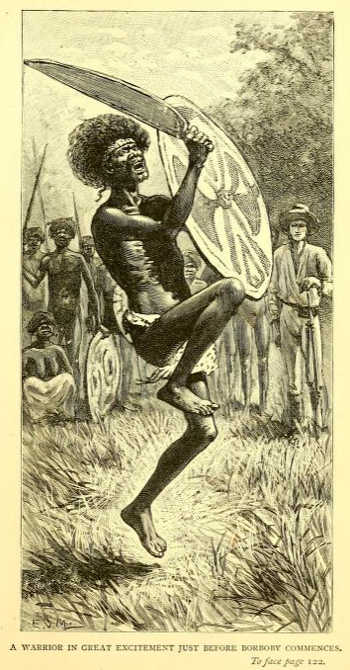

A couple of hours before sunset we crossed Herbert River for the third time, and landed near a high bank, which it was very difficult for the horse to climb. Here I was surprised to find a very large grassy plain, made, as it were, expressly for a tournament. Immediately in front of me was a tolerably open forest of large gum-trees with white trunks, then a large open space, and beyond it another grove of gum trees. On the west side of the plain was Herbert River, and farther to the west, on the other side of the river, was Sea View Range, behind the summits of which the sun was soon to set. The battlefield was bounded on the east by a high hill clad from base to top with dark green scrubs, which, in the twilight, looked almost black by the side of the fresh bright green of the grass and the white gum-trees. Near the edge of the woods Jacky's men and the savages who had joined us on the road made a brief pause. One of those who had last arrived began to run round in a challenging manner like a man in a rage. He was very tall (about 6 feet 4 inches), and like some of the natives in this neighbourhood, his hair bore a strong resemblance to that of the Papuans, being about a foot and a half long, closely matted together, and standing out in all directions. Shaking this heavy head of hair like a madman, with head and shoulders thrown back, he made long jumps and wild leaps, holding his large wooden sword perpendicularly in front of him in his right hand, and the shield in his left.

When he had run enough to cool his savage warlike ardour he stopped near me. He was so hot that perspiration streamed from him, and the red paint ran in long streaks down his face. Around his head he wore a very beautiful brow-band, for which I offered him a stick of tobacco, and he immediately untied it and gave it to me. It was an extraordinarily neat piece of work, like the finest net, four inches wide, and made of plant fibre forming a delicate and regular texture. The whole was painted red. I saw two others who sold me their brow-bands for tobacco, so that I secured three of these valuable pieces of handiwork.

Meanwhile the enthusiastic warrior from whom I had purchased the first brow-band was again busy taking great leaps; gradually the conversation became more lively, the warlike ardour increased, and all held their weapons in readiness.

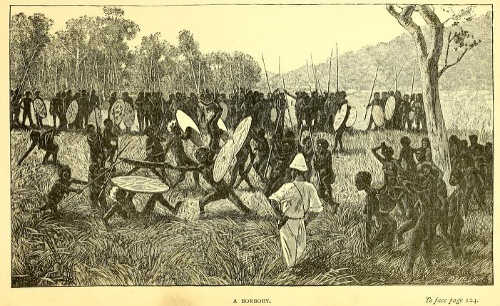

Suddenly an old man uttered a terrible war-cry, and swung his bundle of spears over his head. This acted, as it were, like an electric shock on all of them; they at once gathered together, shouted with all their might, and raised their shields with their left hands, swinging swords, spears, boomerangs, and nulla-nullas in the air. Then they all rushed with a savage war-cry through the grove of gum trees and marched by a zigzag route against their enemies, who were standing far away on the other side of the plain. At every new turn they stopped and were silent for a moment, then with a terrific howl started afresh, until at the third turn they stood in the middle of the plain directly opposite their opponents, where they remained.

I fastened up my horse at some distance and followed them as quickly as I could; the women and children also hastened to the scene of conflict. The strange tribes on the other side stood in a group in front of their huts, which were picturesquely situated near the edge of the forest, at the foot of the scrub-clad hill. As soon as our men had halted, three men from the hostile ranks came forward in a threatening manner with shields in their left hands and Swords held perpendicularly in their right. Their heads were covered with the elegant yellow and white topknots of the white cockatoos. Each man wore at least forty of these, which were fastened in his hair with beeswax, and gave the head the appearance of a large aster. The three men approached ours very rapidly, running forward with long elastic leaps. Now and then they jumped high in the air like cats, and fell down behind their shields, so well concealed that we saw but little of them above the high grass. This manoeuvre was repeated until they came within about twenty yards from our men; then they halted in an erect position, the large shields before them and the points of their swords resting on the ground, ready for the fight. The large crowd of strange tribes followed them slowly.

Now the duels were to begin; three men came forward from our side and accepted the challenge, the rest remaining quiet for the present.

The common position for challenging is as follows: the shield is held in the left hand, and the sword perpendicularly in the right. But, owing to the weight of the sword, it must be used almost like a blacksmith's sledge-hammer in order to hit the shield of the opponent with full force; the combatant is therefore obliged to let the weapon rest in front on the ground a few moments before the duel begins, when he swings it back and past his head against his opponent. When one of them has made his blow, it is his opponent's turn, and thus they exchange blows until one of them gets tired and gives up, or his shield is cloven, in which case he is regarded as unfit for the fight.

While the first three pairs were fighting, others began to exchange blows. There was no regularity in the fight. The duel usually began with spears, then they came nearer to each other and took to their swords. Sometimes the matter was decided at a distance, boomerangs, nulla-nullas, and spears being thrown against the shields. The natives are exceedingly skilful in parrying, so that they are seldom wounded by the first two kinds of weapons. On the other hand, the spears easily penetrate the shields, and sometimes injure the bearer, who is then regarded as disqualified and must declare himself beaten. There were always some combatants in the field, frequently seven or eight pairs at a time; but the duellists were continually changing.

The women gather up the weapons, and when a warrior has to engage in several duels, his wives continually supply him with weapons. The other women stand and look on, watching the conflict with the greatest attention, for they have much at stake. Many a one changes husbands on that night. As the natives frequently rob each other of their wives, the conflicts arising from this cause are settled by borboby, the victor retaining the woman.

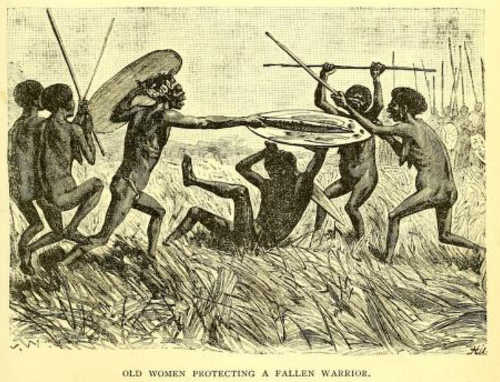

The old women also take part in the fray. They stand behind the combatants with the same kind of sticks as those used for digging up roots. They hold the stick with both hands, beat the ground hard with it, and jump up and down in a state of wild excitement. They cry to the men, egging and urging them on, four or five frequently surrounding one man, and acting as if perfectly mad. The men become more and more excited, perspiration pours from them, and they exert themselves to the utmost.

If one of the men is conquered, the old women gather around him and protect him with their sticks, parrying the sword blows of his opponent, constantly shouting, "Do not kill him, do not kill him!"

In order that the natives might not suspect me of hostile purposes I had, in the presence of all, put my gun against the trunk of a gum-tree hard by, thus at the same time showing them that I was not unarmed. I went to the fighting-ground and took my place among the spectators, consisting chiefly of women. The Kanaka, being a foreigner, felt insecure, and thought it wisest to stay near me. He had borrowed one of Mr. Walters' revolvers at the station, hoping thereby to inspire the blacks with respect; but as it was so rusty and worn that it usually missed fire, he had finally lost all faith in its virtue as a weapon of terror.

With the greatest attention I watched the interesting duels, which lasted only about three-quarters of an hour, but which entertained me more than any performance I ever witnessed. Where the conflict was hottest my friend Jacky stood cool and dignified, and was more than ever conscious of his civilised superiority. The old white body evidently inspired the multitude with awe. Boomerangs and nulla-nullas whizzed about our ears, without however hindering me from watching with interest the passion of these wild children of nature - the desperate exertions of the men, the zeal of the young women, and the foolish rage of the old women, whose discordant voices blended with the din of the weapons, with the dull blows of the swords, with the clang of the nulla-nullas, and with the flight of the boomerangs whizzing through the air. Here all disputes and legal conflicts were settled, not only between tribes but also between individuals. That the lowest races of men do not try to settle their disputes in a more parliamentary manner need not cause any surprise, but it may appear strange to us that aged women take so active a part in the issue of these conflicts.

With the exception of the murder of a member of the same tribe, the aboriginal Australian knows only one crime, and that is theft, and the punishment for violating the right of possession is not inflicted by the community, but by the individual wronged. The thief is challenged by his victim to a duel with wooden swords and shields; and the matter is settled sometimes privately the relatives of both parties serving as witnesses, sometimes publicly at the borboby, where two hundred to three hundred meet from various tribes to decide all their disputes. The victor in the duel wins in the dispute.

The robbery of women, who also among these savages are regarded as a man's most valuable property, is both the grossest and the most common theft; for it is the usual way of getting a wife. Hence woman is the chief cause of disputes. Inchastity, which is called gramma, i.e. to steal, also falls under the head of theft.

The theft of weapons, implements, and food is rarely the cause of a duel. I do not remember a single instance of weapons being stolen. If an inconsiderable amount of food or some other trifle has been stolen, it frequently happens that the victim, instead of challenging the thief, simply plays the part of an offended person, especially if he considers himself inferior in strength and in the use of weapons. In cases where the food has not been eaten but is returned, then the victim is satisfied with compensation, in the form of tobacco, food, or weapons, and thus friendship is at once re-established.

Even when the thief regards himself as superior in strength, he does not care to have a duel in prospect, for these savages shrink from every inconvenience. The idea of having to fight with his victim is a greater punishment for the thief than one would think, even though bloodshed is rare.

In these duels the issue does not depend wholly on physical strength, as the relatives play a conspicuous part in the matter. The possession of many strong men on his side is a great moral support to the combatant. He knows that his opponent, through fear of his relatives, will not carry the conflict to the extreme; he is also certain that, if necessary, they will interfere and prevent his getting wounded. The relatives and friends are of great importance in the decision of conflicts among the natives, though physical strength, of course, is the first consideration.

After such a conflict the reader possibly expects a description of fallen warriors swimming in blood; but relatives and friends take care that none of the combatants are injured. Mortal wounds are extremely rare. Mangoran had received a slight wound in the arm above the elbow from a boomerang, and was therefore pitied by everybody. In the next borboby one person happened to be pierced by a spear, which, being barbed, could not be removed. His tribe carried him about with them for three days before he died.

As soon as the sun had set the conflict ceased. The people separated, each one going to his own camp, all deeply interested in the events of the day. There was not much sleep that night, and conversation was lively round the small camp fires. As a result of the borboby several family revolutions had already taken place, men had lost their wives and women had acquired new husbands. In the cool morning of the next day the duels were continued for an hour; then the crowds scattered, each tribe returning to its own "land." While I remained at Herbert River four borbobies occurred with three to four weeks intervening between each, in the months of November, December, January, and February - that is, in the hottest season of the year. During the winter no borboby is held.