Pleasant companions - Two new mammals - Large scrubs in the Coast Mountains - The lawyer-palm - "Never have a black-fellow behind you" - I decide to live with the blacks - Great expectations - My outfit - Tobacco is money – The baby of the gun.

No person can spend many days with the Australian natives before finding out that one of their chief traits is their never-ceasing begging. If you give one thing to a black man, he finds ten other things to ask for, and he is not ashamed to ask for all that you have, and more too. He is never satisfied. Gratitude does not exist in his breast, and friendship he is unable to appreciate. An Australian native can betray anybody, and confidence can rarely be placed in him. You should never let him walk behind you, but always in front. There is not one among them who will not lie if it is to his advantage. Though it is their nature to be lazy, and though they have no inclination whatever for work, yet they can on a hunt develop remarkable energy and endurance.

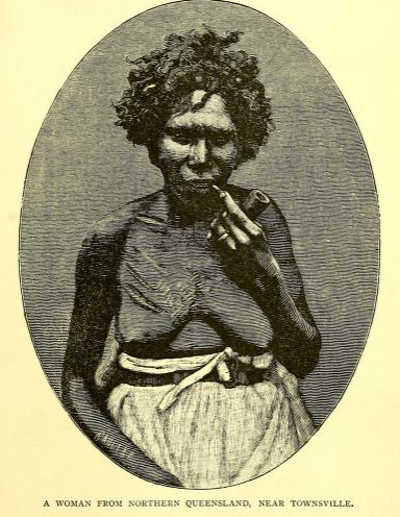

The women are the humble servants or rather slaves of the native. He does only what pleases himself, and leaves all work to his wives; therefore the more wives he has the richer he is.

The Australian aborigines do not cultivate the soil, and their only domestic animal is the dingo (dog). Living from hand to mouth on vegetables or animal flesh, they are constantly flitting from place to place to find their subsistence, and have no permanent abodes. Their character is like their mode of life; they are the children of the moment - capricious; a resolution is quickly formed and as quickly abandoned. They are humorous by nature, have a keen sense of what is comical, and a cheerful disposition; though free from care, they are never without a secret fear of being attacked by other tribes, for the tribes are each other' s mortal foes.

What they lack in personal courage they make up by craft and cunning. If they can kill their enemies by a treacherous attack, they do so without hesitation. The attacked party takes to flight, each one thinking of his own safety alone, for self-preservation is their only law. The Australians are cannibals. A fallen foe, be it man, woman, or child, is eaten as the choicest delicacy; they know no greater luxury than the flesh of a black man. There are superstitious notions connected with cannibalism, and though they have no idols and no form of divine worship, they seem to fear an evil being who seeks to haunt them, but of whom their notions are very vague. Of a supreme good being they have no conception whatever, nor do they believe in any existence after death. Such are in brief the main characteristics of the Australian native as I came to know him on the Herbert River.

During my association with these savages I learned that on the summit of the Coast Mountains, before mentioned, there lived two varieties of mammals which seemed to me to be unknown to science; but I had much difficulty in acquiring this knowledge. One of the animals they called yarri. From their description I conceived it to be a marsupial tiger. It was said to be about the size of a dingo, though its legs were shorter and its tail long, and it was described by the blacks as being very savage. If pursued it climbed up the trees, where the natives did not dare follow it, and by gestures they explained to me how at such times it would growl and bite their hands. Rocky retreats were its most favourite habitat, and its principal food was said to be a little brown variety of wallaby common in Northern Queensland scrubs. Its flesh was not particularly appreciated by the blacks, and if they accidentally killed a yarri they gave it to their old women. In Western Queensland I heard much about an animal which seemed to me to be identical with the yarri here described, and a specimen was once nearly shot by an officer of the black police in the regions I was now visiting.

The other animal also lived in the trees, but fed exclusively on leaves. According to the statement of the blacks, it was a kangaroo which lived in the highest trees on the summit of the Coast Mountains. It had a very long tail, and was as large as a medium-sized dog, climbed the trees in the same manner as the natives themselves, and was called boongary. I was sure that it could be none other than a tree-kangaroo (Dendrolagus). Tree kangaroos were known to exist in New Guinea, but none had yet been found on the Australian continent.

As is well known, the Great Dividing Range stretches along the coast of Australia at a distance of from fifty to some three hundred miles inland. This range forms in general the watershed between the eastern and western waters, but there are chains of mountains visible from the coast that are often of greater elevation than this range, such as the Blue Mountains, where the streams break through the mountain masses in picturesque chasms on their way to the Pacific. The Dividing Range is sometimes not easily traced, and the spurs coming from it, as well as detached mountains near the coast, are often much higher and are frequently taken for the main range. The whole body of mountains from south to north is spoken of as the Great Dividing Range, and forms, as it were, the Australian Cordilleras. On the extreme south-east the mountains attain an elevation of 5,000 to 6,000 feet; going north, they diminish rapidly and considerably. In the south part of Queensland they are low, but in Northern Queensland they again rise to a height of 2,000 to 4,000 feet (the Bellenden Kerr Hills are even 5,400 feet high), then they once more diminish, and gradually disappear into the low-lying country of Cape York. The moist monsoons blow over these mountains and are converted into rain, which, together with the warm climate, produces a luxuriant tropical vegetation. Hence these mountains from base to top are extensively covered with scrubs.

On Herbert River and northward the Coast Mountains are difficult of access. Perpendicular chasms and tracts covered with loose stone abound; but wherever a root could take hold large trees and bushes have grown, while creeping and twining plants form a carpet on the ground. There are hilly but less stony parts, where the vegetation is so dense that a person can hardly penetrate it without being so torn and pricked that blood flows from the wounds.

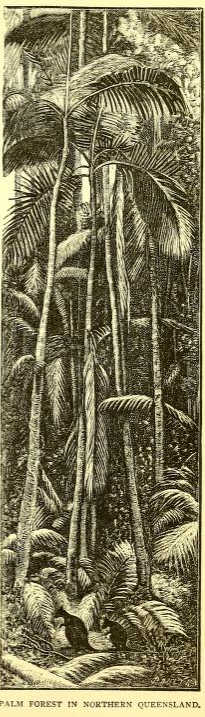

In the mountain scrubs there grows a very luxuriant kind of palm (Calamus australis), whose stem, of a finger's thickness, like the East Indian Rotang-palm, creeps through the woods for hundreds of feet, twining round trees in its path, and at times forming so dense a wattle that it is impossible to get through it. The stem and leaves are studded with the sharpest thorns, which continually cling to you and draw blood, hence its not very polite name of lawyer-palm.

In the lower regions the common Australian palm and the fan palm (Livistonia) are found. There is also the beautiful banana palm, with its bright green, and towards the summit magnificent tree ferns spread their splendid leaves over the rivers in the humid vales, blending with the endless mass of other trees and bushes. Rivers and streams everywhere tumble down the mountain sides, and frequently form beautiful waterfalls surrounded by luxuriant scrubs. Here, in the shadow of dense trees hiding the sun from sight, the water is cool and clear as crystal.

The real scrubs once left behind, and the summit reached, you come to a more open country, Leichhardt's basaltic tableland. At first there are hills and dales with the same kind of scrubs as below, but not so dense, for the lawyer-palm is here more rare.

In these picturesque but very inaccessible scrubs the natives live in large numbers undisturbed by the white man, for there is no gold or other treasure to tempt him to subject himself to all the inconveniences connected with the effort to penetrate into these regions.

After having studied the neighbourhood of the station for some time, I soon discovered that I must abandon Herbert Vale as my night quarters and go farther up into the wild woods of the Coast Mountains, where there was much to entice me. Here I was to find the natives in their original condition, uninfluenced by intercourse with the white man. I had long desired to study these savages - the Australian aborigines, the lowest of the human race - in their actual conditions of existence; for the ethnological student no phase of human life is so interesting as the most primitive one. It also seemed clear at the outset that new species of animal life must be found there, and that I might secure them with the aid of the blacks. Having heard them speak of the two remarkable mammals, I resolved to do all in my power to get into these regions. But I could not think of going by myself; I needed help to carry my baggage, and not having any white servant, I was obliged to select black attendants, the only ones of course who could be of any real service to me in the scrubs. It would, moreover, be very difficult to find a capable white man willing to accompany me. In all probability he would not understand how to treat the savages, and this might soon result in death for both of us. It is difficult for a white man to find his way in these pathless regions; besides, it is not likely he would be able to trace the wild animals without the aid of the natives who have their hunting grounds here. My only choice was to secure natives, and make them my friends and comrades, if I wished to attain my purpose; and so I resolved to live surrounded by them alone.

My first object was to find persons willing to go with me; no easy task, for the "civilised" natives on Herbert River were very lazy, and did not care to go up into these mountain regions; besides, they were but poorly acquainted with them. I therefore had to address myself to more remote tribes living nearer the regions which were my goal. From the civilised blacks I had become tolerably well acquainted with the natives. I knew a little of their language, and having had some experience of the manner in which to treat them in order to make them useful to me, I felt comparatively safe; but I must confess to considerable curiosity as to what the result would be.

It was a new experience to a white man; this camping with Australian natives, who dwell in miserable huts made of leaves, who have no domestic animals, and are ignorant of agriculture, as well as savage and treacherous. A human life has so little value for them that they think no more of killing a man than we of breaking a glass; provided they feel sufficiently safe, they will kill a white man for a piece of tobacco or a shirt. But on picturing to myself the very interesting life in store for me, my doubts and hesitations were overcome. I was now to have a splendid opportunity of studying these natives. I was to be with them in sunshine and in rain in their own forests; to see them uninfluenced by any form of civilisation, and in their company to make many interesting discoveries and observations.

In the course of this and the following year I made many expeditions in company with the blacks. I began with the nearest tribes and worked my way up through these to the more remote ones, until at last I lived in huts with natives of Australia who never come into contact with the white man.

My supplies on these expeditions usually consisted of from ten to twelve pieces of salt beef in a bag, about thirty pounds of wheat flour for baking damper, and a small sack of sugar. Instead of tea I drank simply sugar-water. It is a cooling pleasant drink, especially when the water is as clear and good as in Northern Queensland.

When my provisions were consumed - and they never lasted very long, for the natives liked them too well - I lived on their fare, which was anything but savoury. If I had been obliged to depend on their vegetable food I should soon have starved to death, but fortunately the large lizards, snakes, larvae, eggs, etc., and what I shot for myself, to some extent took the place of civilised food. The worst was when the sugar gave out, for the plain dishes on which I had to depend went down much more easily with sweet water. I had no canned food, and of stimulants, which as a rule I consider superfluous in the tropics, I had only a bottle of whisky. I never carried salt, and, like the natives, I experienced no inconvenience from the want of it when eating eggs, lizards, fish, game, etc.

As money I used tobacco; my provisions served the same purpose, and these were swallowed by the natives, no matter how satiated they might be with other food. When I ran short of tobacco I was always obliged to go back to the station. Even such things as a shirt or a handkerchief so fell in value when tobacco was wanting as to be almost worthless.

The natives along Herbert River, who do not come in contact with white people, have but few wants. They never wear clothes either winter or summer, and consequently money has no value. Their only drink is water or water mixed with honey. The blacks of Herbert River have no stimulants, and this is the secret of the influence of tobacco, which they value so highly that they sometimes wrap a small piece of about three to four inches long in grass, in order to enjoy it later with allied tribes with whom they are on a friendly footing, or they may send it in exchange for other advantages to another tribe. In this manner the use of tobacco may be known among tribes who have never seen a white man. The tobacco is not chewed, but only smoked, and they believe that it is good for everybody; I have even seen a mother put a pipe into the mouth of her babe, which was sitting on her shoulder, and the little one apparently enjoyed a whiff.

Besides tobacco, which I continually dealt out in small quantities to maintain its value, I had to take with me clay pipes, for the blacks cannot even make such things as these. Still, it was more easy to satisfy them with pipes, for the whole camp was usually content with one or two, which were passed from mouth to mouth.

Of kitchen utensils I took with me only a tin pail to fetch and keep water in, and a knife, for I soon learned from the natives how to prepare my food in a less elaborate manner than that adopted in a civilised kitchen, so that I easily got on without kettle or frying pan, hunger and fatigue making sauce and spices superfluous. In addition to the necessary chemicals for preserving specimens, I carried with me a small flask of quinine, two bottles containing medicine for the stomach, and one containing ammonia as an antidote to serpent bites; this and a small amount of lunar caustic constituted my whole drug store.

A light merino shirt, a coloured shirt, a pair of corduroy trousers, two pairs of cotton socks, and a pair of shoes, constituted my whole wardrobe. For the night I had a large, double, white woollen blanket in which to wrap myself, and a piece of mackintosh about two yards square, which I spread out on the ground to lie upon. I also always took with me an overcoat, which I put on when it rained. For my toilet I had a toothbrush, a piece of soap, and a towel. I let my hair grow until I came to the station, where the keeper, who had been a sheep-shearer, plied the shears as a hair-cutter with all his accustomed skill.

My watch and compass were left at Herbert Vale, for it was important to be as unencumbered as possible. With the natives I learned to determine time by the sun, and what was lacking in my ability to find my bearings was supplied by the remarkable instinct of the blacks for finding their way everywhere. A double-barrelled gun and an excellent American revolver were of course the most important parts of my whole equipment, which, as has been shown, was plain, but I was obliged to limit my necessities as much as possible. The natives, who dislike to carry anything, looked upon everything save provisions and tobacco as luxuries.

The gun and revolver had even more power over them than the tobacco. The Australian aborigines are in great fear of firearms, for they themselves do not even use bows and arrows, except in the outlying parts of Cape York, where they have some clumsy weapons of this kind. But you must be careful not to miss your mark in their presence. You must hit all you aim at, or they will lose their respect for you. It makes no difference whether the object you shoot at is in motion or not; they are as much surprised when an opossum is brought down from his tree as when the swiftest bird is shot on the wing. When I was not quite sure of my shot, I took good care not to use the revolver, for it is difficult, as everybody knows, to hit the mark with this weapon. They had great respect for the baby of the gun, as they called the revolver, believing that it never ceased shooting, and I need not add that I allowed them to retain this belief As a rule they were so afraid of the baby that they did not care to touch it. It was in my belt day and night.

It was exceedingly difficult to secure men among the lazy natives for these expeditions; at first my friend Jacky assisted me. On account of his strength and cunning he was highly respected, and looked upon as the first man in his tribe, and he supported me with his influence. First, it was necessary to get him to tell me who were the best hunters, and then, by promising him tobacco, I either got him to go with me to the tribe in question or to find another person willing to do so.

It sometimes took several days to find these people and treat with them. Frequently they changed their minds, and as they were continually moving from place to place I had to give Jacky more tobacco and take a fresh start to find them. At last I would get my people together. As a rule I was attended by five or six young men, sometimes by more, sometimes by less; occasionally women and children, even the whole tribe, went with me. The natives led the way, the one immediately before me leading the pack-horse, while I followed on horseback.

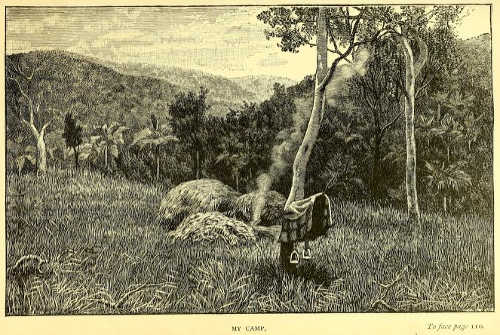

On the first expeditions it only took us a day or two to get to the base of the mountain range. Here we selected a convenient spot for a camp; a place where there was plenty of grass and water for the two horses, which could not go with us into the large dense scrubs. Their forefeet were hobbled, and they were left to themselves during our absence.

The next morning we were ready to proceed on our journey, the saddles and bridles were hung up in the trees in order that they might not be consumed by wild dogs, my baggage was divided among the natives, and the ascent of the scrub-clad mountain began.

As it is easier to get through the scrubs along a riverbed, over stones and crevasses, than it is to crawl through the dense brushwood and be pricked by thorns and sharp branches, we as a rule followed a mountain stream to reach the summit, where were my real hunting grounds. We frequently made long journeys across the tableland, but every expedition was of course not precisely like the one above described. As a rule we went as far as possible on horseback, then we would penetrate the scrubs and gain the tablelands, where the scrubs, as above indicated, appear in patches of various sizes, partly as isolated groves and partly as a continuation of the forests which cover the ridges next to the ocean.

Every evening I pitched my camp and slept in a hut of leaves built exactly like those of the natives, except that it was a little more tightly put together, so that it usually afforded me protection from the rain. It was put up very hastily just before sundown. A few branches were stuck in the ground and their tops united, and this framework was covered with large leaves of the banana or other palms, or with long grass. A door was out of the question; there was simply an opening large enough for me to crawl through, for the whole hut was not higher than my shoulders.

Such is also the mitta, the abode of the natives, which is intended only for a short stay, and adapted to the nomadic life of these people. I took care to have my hut made long enough to enable me to lie straight, and to see that my bed was perfectly horizontal, a matter of no importance to the blacks. It makes no difference to them whether the feet lie higher or lower than the head. My people were on either side of the entrance to my hut, where they built flimsy roofs of trees and grass; if there was promise of fine weather for the night, they simply cut down a tree and laid themselves by the side of it. In the centre a fire was kept burning.

Every evening, before going to sleep, I went outside my hut and fired my revolver to remind my companions of the existence of this terrible weapon, and in case we were on the territory of strange tribes, to keep them from attacking us. This precaution was my way of saying good-night to my men. I may add that I never had exactly the same companions on these various expeditions, because it is necessary that the blacks should not become too well acquainted with you: as long as they respect the white man it is less dangerous to camp with them; but as soon as they become familiar with his customs and find out that there is no danger in associating with him, he is liable at any moment to a treacherous assault.

That I was not killed by my men (a circumstance which white people whom I have met have wondered at), I owed to the fact that they never wholly lost their respect for my firearms. At first, at least, I was regarded by them as something inexplicable - as a sort of mysterious being who could travel from land to land without being eaten, and whose chief interest lay in things which, in their eyes, were utterly useless, such as the skins and bones of slain animals.

There was a peculiar protection to me in the fortunate circumstance that they imagined that I did not sleep, and I think this was the chief reason why they did not attack me in the night. During the winter, when there was a great difference between the temperature of the night and that of the day, the cold was very trying to me, and I awoke regularly once or twice in the night when our large camp fire had gone out. All my men lay entirely naked around the extinguished fire; some sleeping, others cold and half awake, who, however, thought it too much of an effort to go after fuel. I then usually called one of them, and by promising tobacco - and I had made them accustomed to have entire confidence in my words - induced him to go out in the dark night and procure more fuel.

By being thus perpetually disturbed they acquired the idea that the "white man" was always on the alert and had the "baby of the gun" ready.