The appearance of the aborigines in the different parts of the continent - My pack-horse in danger - Tracks of the boongary (tree-kangaroo) - Bower-birds - The blacks in rainy weather - Making fire in the scrubs - A messenger from the civilised world - The relations of the various tribes - Tattooing

The natural conditions varying in different parts of Australia, a fact not to be wondered at in so large a continent, the natives also vary in physical and mental development. Mr B. Smyth is of opinion that the natives in the different parts of the country are as unlike each other in physical structure and colour of skin as the inhabitants of England, Germany, France, and Italy. The following description applies mainly to the natives on the Herbert river.

The southern part of Australia is, both as regards natural condition and climate, so unlike the tropical north that the mode of life of the natives is materially modified. Thus in the south-eastern part the natives live mainly on animal food, while in the tropical north they subsist chiefly on vegetables. This has no slight influence on their physical development. Those that live near bodies of water, and have an opportunity of securing fish in addition to game and other animal food, are more vigorous physically than those who have to be satisfied with snakes, lizards, and indigestible vegetables - the latter affording but little nourishment. I found the strongest and healthiest blacks in the interior of Queensland, on Diamantina River, where even the women are tall and muscular. According to trustworthy reports the same is true of the natives on Boulya and Georgina Rivers, farther west. In the coast districts of Queensland they seem to me to be smaller of stature and to have more slender limbs. It is, however, asserted by other writers that the most powerful natives are to be found on the coast.

Farther south in Australia the climate is cool, and hence the natives have to protect themselves with blankets made of opossum skin, things not needed in the northern part of the continent, where they roam about naked both winter and summer. Upon the whole the struggle for existence is more severe in the south, but as a compensation the natives there attain a higher intellectual development.

The natives in one part of Australia have words for numbers up to four or five, while in other parts they have no terms beyond three. The natives along Herbert River have very crude and confused religious notions, but it is claimed that even an idea of the Trinity, strikingly like that of the Christian religion, has been discovered among tribes in the south-eastern part of the continent; idolatry exists nowhere in Australia. The blacks in the north-western part of the continent are praised for their honesty and industry, and are employed by the colonists in all kinds of work at the stations. In the rest of Australia the natives are treacherous and indolent.

According to the investigations of Dr. Topinard there are two different types of men among the natives of Australia. Those of the lower type are small and black, have curly hair, weak muscles, and prominent cheek-bones. The higher type, on the other hand, are taller, have smooth hair, and a less dolichocephalous form of head. This also agrees with the reports of travellers; at all events, there is no doubt that the tribes of Northern Queensland are inferior to those found in the southern part of the continent, and a theory has been presented that the higher race living mainly in the southern part of Australia has been a race of conquerors who have subjugated the weaker and driven them to the north.

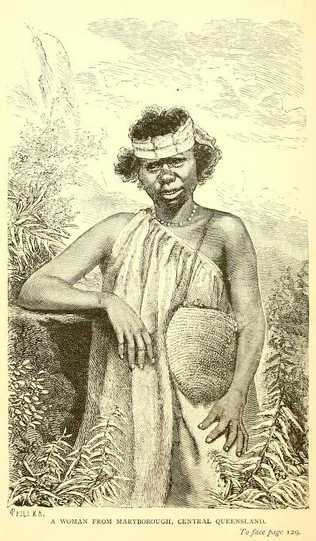

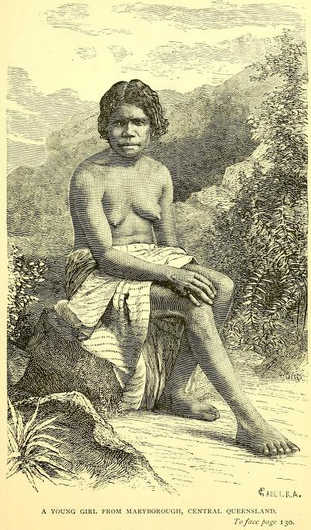

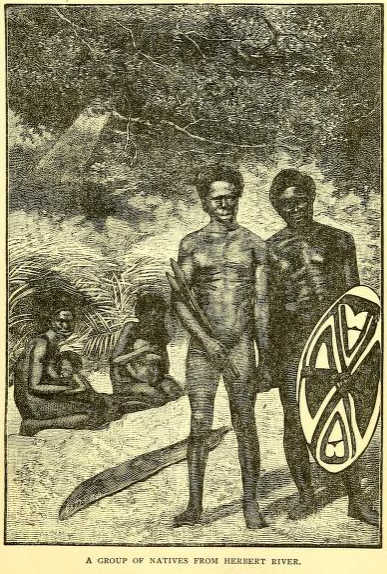

In New South Wales the average size of the tribes is tolerably high, and equals that of Europeans (5 ft. 2 in. to 5 ft. 6 in.) At Murrumbidgee the natives are of medium height. Round Lake Torrens they attain, according to Stuart, a height of only 3 ft. 8 in., while the average height in the interior is 5 ft. 11 in. During my sojourn on the Diamantina River I heard of a black at Mulligan (twenty-five miles west of Georgina) who was about 7 ft. high. He was well known at the stations out there, and died just before my arrival. In the coast districts along the eastern side of Queensland they are small, while along Herbert River their size was surprisingly irregular; few of them could be called corpulent, a large number were in good condition and well formed though their necks were somewhat short, while others were lean and slender.

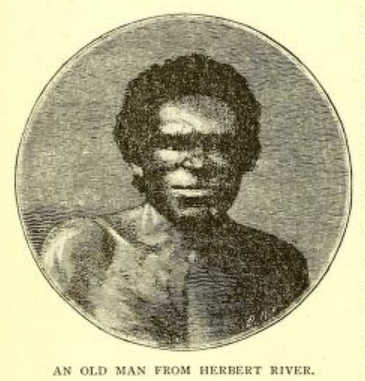

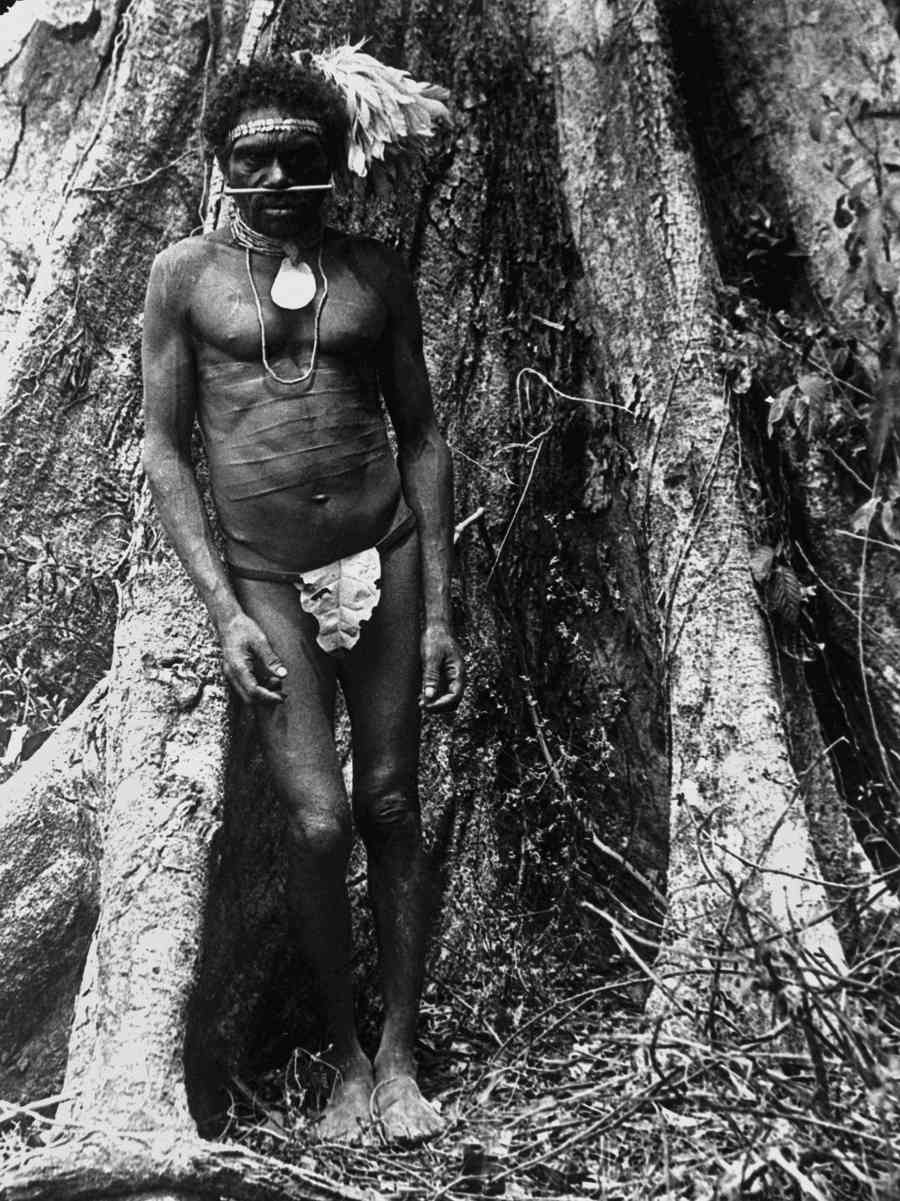

The most characteristic feature of an Australian's face is the low receding forehead and the prominence of the part immediately above the eyes. The latter might indicate keen perception, and in this they are not lacking. Their eyes are expressive, dark brown, frequently with a tinge of deep blue. The white of the eye is of a dirty yellow colour and very much bloodshot, which gives them a savage look. The nose is flat and triangular, and narrow at the top, thus bringing the eyes near together. The partition between the two nostrils is very large and conspicuous. Many of the natives pierce it and put yellow stick into it as an ornament. My men, who of course had neither pockets nor pipe-cases, frequently put their pipes into these holes in their noses as a convenient place to keep them, and fancied that their noses looked all the better for it. Now and then I met men whose noses were almost Roman, and there were all the transitional forms between these and the flat triangular noses. I have also heard of high aquiline noses among the natives of New South Wales. I think it probable that the large noses sometimes found in Northern Queensland may be attributed to a mixture with Papuans, whose noses are known to be their pride. The irregular size of their bodies is evidence in the same direction.

The Australian aborigines have high cheek-bones and large, open, ugly-looking mouths. But the blacks on Herbert River usually keep their mouths shut, which improves their looks, and they are, upon the whole, a better looking race than the natives in the south. Their lips are a reddish-blue, and they have small receding chins. Their muscular development is usually slight and their legs and arms are particularly slender; still I have seen many exceptions to this rule. The women are always knock-kneed, and this is often the case with the men, although with them it is not nearly so marked, their legs being almost straight. They are seldom bow-legged to any great extent. The feet, which as a rule are large, leave footprints that are either straight or show the toes slightly turned outward. They have great skill in seizing spears and similar objects with their toes, and in this way they avoid stooping to pick up things.

Though the natives are slender, they have a remarkable control over their bodies. They bear themselves as if conscious that they are the lords of creation, and one might envy them the dignity and ease of their movements. The women carry themselves in a dignified manner, and do not look so savage as the men.

The hair and beard, which are as black as pitch, are slightly curly, but not woolly, like those of the African negro I seldom saw straight hair on the blacks near Herbert River (I should say not over five per cent had straight hair), but it is quite common in the rest of Australia, especially in the interior. Men and women wear hair of the same length. I only once saw a man with his hair standing out in all directions, like that of the Papuans. There is generally little hair on the rest of the body. Some of the old men near Herbert River had a heavy growth of hair on their breasts and partly on their backs and arms, a fact I have never observed among the women. The natives along Herbert river had but little beard, and they constantly pulled out what little they had. In the rest of Australia men are frequently met with who have fine beards, but they do not themselves regard the beard as an ornament. In New South Wales even women are found with a heavy growth of beard. The hair and beard of the Australian are not coarse, and would be bright and beautiful if he were more cleanly. On Balonne River in Queensland there is a family (not a tribe) of persons who are perfectly hairless. Old individuals sometimes have snow-white hair, but, so far as I know, albinos have never been discovered in Australia.

The natives of Australia are called blacks, but as a rule they are chocolate brown; this colour is particularly conspicuous when they are under water while bathing. Their complexion manifestly changes with their emotions; they turn pale from fear - that is to say, the skin assumes a grayish colour. I have even seen young persons, whose skin is thin and transparent, blush. Infants are a light yellow or brown, but at the age of two years they have already assumed the hue of their parents.

The race must be characterised as ugly-looking, though the expression of the countenance is not, as a rule, disagreeable, especially when their attention is awakened. Occasionally handsome individuals may be found, particularly among the men, who as a rule are better shaped than the women. The latter have more slender limbs; the abdomen is prominent, and they have hanging breasts, mainly the result of hard work, unhealthy vegetable food, and early marriage. I have on two occasions seen what might be called beauties among the women of Western Queensland. Their hands were small, their feet neat and well shaped, with so high an instep that one asked oneself involuntarily where in the world they had acquired this aristocratic mark of beauty. Their figure was above criticism, and their skin, as is usually the case among the young women, was as soft as velvet. When these black daughters of Eve smiled and showed their beautiful white teeth, and when their eyes peeped coquettishly from beneath the curly hair which hung in quite the modern fashion down over their foreheads, it is not difficult to understand that even here women are not quite deprived of that influence ascribed by Goethe to the fair sex generally. On the Herbert River I never saw a beautiful girl, but about seventy miles west from there, on the tableland, I met a young woman who had a good figure and a remarkably symmetrical face, beautiful eyes, and a well-shaped nose. the lower part of which was narrower than is usual, and consequently the triangular form was less conspicuous. I must confess, however, that I have never seen uglier specimens of human beings than the old women are as they sit crouching round the fire scratching their lean limbs.

They have hardly any muscles left. Their abdomen is large, the skin wrinkled, the hair gray and thin, and the face most repulsive, especially as the eyes are hardly visible. The women fade early, and on account of the hard life they live do not attain the age of the men, the latter living a little more than fifty years. It has been thought that the men in some parts of the interior of Queensland attain an age of even seventy to eighty years, but in the northernmost part of the country few are said to live more than forty years. On Herbert River the women are more numerous than the men; this is also the case among the tribes south-west of the Carpentarian Gulf and elsewhere. But according to accurate observations the opposite is the case in a large part of Australia. The women bear their first children at the age of eighteen to twenty years, sometimes later, and seldom have more than three or four. Twins are very rare.

The birth of a child does not seem to give the mother much trouble. She goes a short distance from the camp, together with an old woman, and when the interesting event has taken place and the child has been washed in the brook, she returns as if nothing had happened, and no one takes the slightest notice of the occurrence. For a long time afterwards she must keep away from her husband. A woman is proud of being with child, and I am able to state as a curiosity that the tribes around the Carpentarian Gulf think they are able to predict the sex of the babe a few months before birth by counting the number of rings on the papillae mammae of the mother.

On account of the unhealthy food of the blacks the children are weaned late, and it even happens that a child is nursed at its mother's breast with the next older brother or sister.

Instances of death from childbearing are very rare. The advent of a baby is not always regarded with favour, and infanticide is therefore common in Australia, especially when there is a scarcity of food, as under such circumstances they even eat the child. In their nomadic life children are a burden to them, and the men particularly do not like to see the women, who work hard and procure much food, troubled with many children. In some parts of Australia the papillae mammae are cut off to hinder the women from nursing children.

The strong smell of the blacks is quite different from that of an unclean white man. Nor can it be doubted that the blacks have a peculiar smell which disturbs cattle, dogs, and horses when they approach the natives, even if the latter are not seen; this, no doubt, has frequently saved the lives of travellers. This strong odour, moreover, is mixed with the smell of dirt, smoke, paint, and other things with which they constantly smear themselves.

The voice the Australian melodious, sometimes hoarse, and gives evidence of musical propensity. Both men and women have a high tone of voice; bass and falsetto voices are rare.

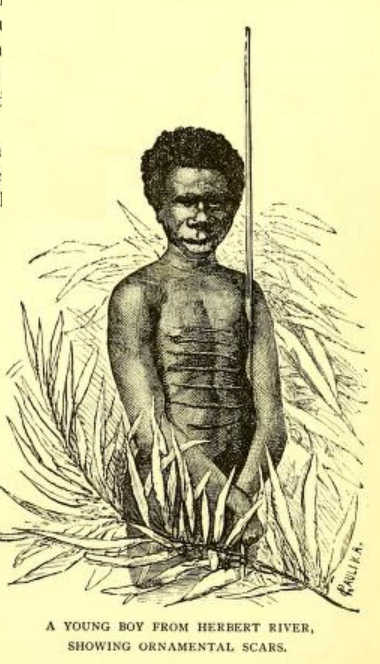

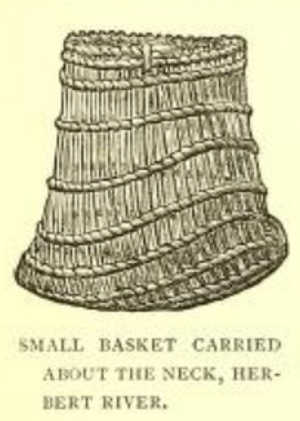

The natives are as fond of decorating their bodies as a sailor is, but they do it clumsily with a sharp stone or a clam shell, with which primitive instruments they cut parallel lines across the breast and stomach. To keep the wounds from healing they put charcoal or ashes in them for a month or two until they swell up into rough ridges. Sometimes they gain the same result by letting ants walk about in the wounds. The shoulders are cut in the same manner, with lines running down three or four inches, making them look as if they had epaulettes. In course of time these peculiar lines, which in young men are conspicuous and as thick as one's little finger, become indistinct, so that on old men they are scarcely visible. They always indicate a certain rank, determined by age. Young boys below a certain age are not decorated, but in course of time they get a few lines across the breast and stomach. Gradually the number of lines is increased, and at last when the lad is full grown, crescents are cut round the papillae of the breast, the horns of the crescent turning outward, thus : ' ) ( ' . This external evidence that the boy is of age is given to him with certain ceremonies, and the strips of skin, which gradually fall off from the wounds as they heal, are gathered in a little basket, which he subsequently carries for some time about his neck until he finally throws its contents out in the woods - gives it to the "devil" as it is called. This is the only trace of a cult that I observed among the blacks of Herbert River, and they doubtless regard it as a sort of sacrifice to avert the wrath of evil spirits. From this time the young man is permitted to eat whatever he pleases, but previously he has been obliged to abstain from certain things, such as eels, large lizards, etc. The transition from boyhood to manhood is not here, as it is in many other parts of Australia, marked by the extraction of one of the front teeth1.

1A gentleman well known to me told me the following about the Rockhampton blacks: "I one day made two or three of those buzzing things, formed by cutting notches in a thin piece of wood with a hole at one end, through which a piece of string is tied ; this instrument is whirled quickly round and round one's head, producing a great noise. I gave these to some black children near my station to play with; directly the noise began the women covered their heads at the command of their men; some of the blacks bolted into the scrub, while two ran up and seized the things from the boys, whom they sent off to the camp. They then told me that in old times these boys would have been killed for seeing those things, which were used only at their "Bora" (transition from boyhood to manhood) ceremonies. I told them that such pieces of wood were common play-things in my country, nevertheless they burnt them in the scrub shortly after."

In addition to these marks of dignity, a man also gets other lines, which are intended as an ornament and are found chiefly on the arms. They are straight, short, parallel lines made in groups across the arm, and the wounds are permitted to heal, so that the lines do not become too prominent. A deep cut here and there is also made on the back or on the shoulder-blade. I never saw the face ornamented by incisions.

The men alone receive the above-described marks of dignity on their chests, stomachs, and shoulders. It is their privilege to be decorated with lines and marks cut in the flesh, and it is not considered proper for women to pay much attention to ornaments. The greatest ornament that a woman ever has is a few clumsy marks across the chest (frequently across the breasts), arms, and back. She is very fond of the ornaments granted her, and the sensitiveness which usually characterises the natives is entirely wanting when they are about to be adorned in this way. I once saw two women engaged in cutting marks on each other's arms with a piece of glass. These marks consisted of short parallel lines down the arms like those worn by the men, but the operation did not seem to give them the least pain, for they smoked their pipes the whole time.

Tattooing in the strictest sense of the word - that is, pricking the skin with a sharp instrument - does not exist among the Australians, but only the above-described custom of cutting wounds in the flesh.

On the same morning that the borboby ended I started on my new expedition, taking this opportunity of securing companions, there being so many blacks assembled. In addition to those who accompanied me on my first expedition I secured three new men. We were to go to another "land," where yarri and boongary were abundant. Tired from the exertions of the previous day, and consequently more lazy than usual, the blacks repeatedly urged me to encamp, although we had travelled only a few miles. We ascended along a mountain stream and passed on our way one of the deserted camps of the blacks, where Pickle-bottle was determined to stop. I called his attention to the fact that the "sun was yet large" (still early in the day), and that neither yarri nor boongary were to be found here; but he replied that there were plenty of them in this locality, and that this was a good place to eat.

He, of course, sulked when I did not yield to his lazy desires, still he continued the march, leading my pack-horse, as he was the most civilised and was best acquainted with the country. Instead of proceeding up the eastern mountain slope, which seemed to be most accessible, he guided us along the foaming stream, of which the bed became more contracted and the banks more steep as we advanced. Still I depended upon Pickle-bottle as our guide, until the path at length became so narrow that progress was impossible. I now understood that he wanted to force me to submit to his will and get me to encamp in the place which he had proposed. I had no other choice but to return by the same way as we had come, until we could find a convenient place for the ascent. With great difficulty the horses were turned, but being angry on account of the delay, I now led the way myself and gave the blacks orders to follow me.

Now and then I looked back to assure myself that I had them all near me. But to my great surprise I discovered at a turn of the way Pickle-bottle and the pack-horse high up the slope, not far from the place where our progress had been blocked. When he saw that I was determined to advance, he wanted to save part of the road, and had resolved to climb with the horse straight over the high and steep precipice. He believed, like most of the blacks, that a horse can go wherever a man can pass. He was just at the point of bringing the horse over the summit - its forefeet were already planted on the top - when it lost its foothold and its balance among the loose stones, and came rolling slowly down the steep slope like a heavy sack of flour. Greatly excited, I expected every moment that it would stop. But it rolled on and on until it came to the edge of the river, where it fortunately stopped.

Pickle -bottle and the other blacks vanished. When they saw that I was becoming angry they were afraid that I would shoot them, so they hid in the scrubs. Calling to them in a friendly tone of voice, I at once began to loosen the pack from the fallen horse. They cautiously peeped at me from behind the trees to see in what mood I was, then they took courage and came out. I now found to my great satisfaction and surprise that the horse, barring a few unimportant scratches, was not injured and had not broken a bone. When we had raised him on to his feet again and washed him in the river, he shook himself, snorted, and seemed to feel as well as ever after his unsuccessful effort to climb the mountain.

We continued the journey, and Pickle-bottle was henceforth less obstinate. "No tobacco to-day. Pickle-bottle," I said to him, a threat which made him very thoughtful. He now easily found the right ascent, and for an hour or two we followed the paths of the blacks up the ridges. The scrubs were very dense on all sides, and the mountains came closer and closer together, until suddenly the landscape expanded into a broad, high valley with grassy plains in the bottom surrounded by scrub-clad hills. Here we encamped on the bank of the river. There was plenty of grass for the horses, for the soil was fertile and the ground had never been used for pasture.

This camp was made the starting-point of many excursions into the surrounding scrubs. One day the blacks showed me traces of boongary on the trunk of a tree. I was now certain of the existence of the animal, and resolved not to give up till I had a specimen in my possession. I did not realise how many annoyances were in store for me, and that I was to wander about for three months before I should succeed in securing it. The traces were old, but still so distinct as to be unmistakable.

On one of these excursions on the top of the mountain I heard in the dense scrubs the loud and unceasing voice of a bird. I carefully approached it as it sat on the ground, and shot it. It was one of the bower-birds already mentioned (Scenopaeus dentirostris), with a gray and very modest plumage, and of the size of a thrush.

As I picked up the bird my attention was drawn to a fresh covering of green leaves on the black soil. This was the bird's place of amusement, which beneath the dense scrubs formed a square about one yard each way, the ground having been cleared of leaves and rubbish. On this neatly cleared spot the bird had laid large fresh leaves, one by the side of the other, with considerable regularity, and close by he sat singing, apparently extremely happy over his work. As soon as the leaves decay they are replaced by new ones. On this excursion I saw three such places of amusement, all near one another, and all had fresh leaves from the same kind of trees, while a large heap of dry withered leaves was lying close by. It seems that the bird scrapes away the mould every time it changes the leaves, so as to have a dark background, against which the green leaves make a better appearance. Can any one doubt that this bird has the sense of beauty?

The bird was quite common. Later on I frequently found it on the summit of the Coast Mountains in the large scrubs, which it never abandons. The natives call it gramma - that is, the thief - because it steals the leaves which it uses to play with.

During the summer there is much rain in the mountains. You are never sure of dry weather, and nearly every night it pours. One day we were overtaken by a heavy shower. The mountain brook grew fast into a torrent, down which we waded to get home, preferring this road to the scrubs, which in rain are impassable and dripping wet and dark.

The natives, who under such circumstances are much more susceptible than Europeans, do not like this sort of weather. When it rained I could never persuade them to accompany me, and they have such a dread of rain that in the wet season they prefer to starve for several days rather than leave their huts in quest of food. They shrugged their shoulders, and shivering with cold, hastened down the brook so fast that I could scarcely keep up with them. On the way we found a place where the mountain formed a shelter, and here the blacks soon discovered with their keen sight that a fire could be built, and so they halted. I could not understand where they would find dry faggots, as everything was dripping wet. It did not take long, however, before the shivering fellows found handfuls of dry rubbish from hollow trees and bundles of leaves from the lawyer- palm. A little fire was soon blazing, and the natives crept round it like kittens, wafting the smoke on to themselves with their hands in order to get warm more quickly.

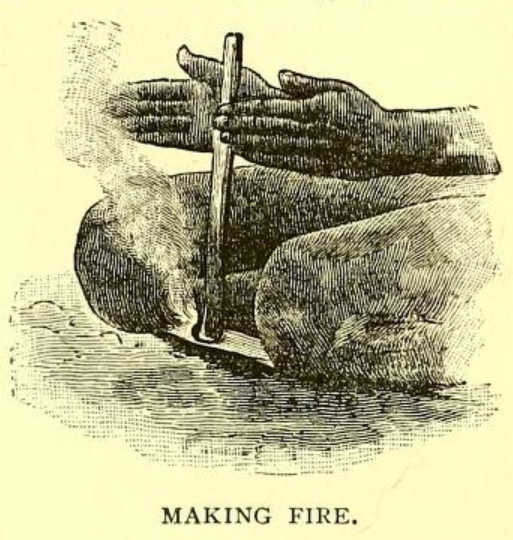

When my men had to make a fire, I usually gave them matches, which they were so delighted to use that they always asked for them to light their pipes with, even when a large fire was burning. They called them mardshe, after the English "matches," a word which I gradually taught them. As a rule, they produce fire with two pieces of light wood from eight to fifteen inches long, either cork-tree (Erythrina vespertilio) or black fig. One piece, which is half of a split branch, is laid on the ground with the flat side up, the other, a round straight stick, is placed perpendicularly on the former, and is twirled rapidly between the hands, so that it is bored into the lower piece, the wood of which is usually of a softer kind.

After a few seconds they begin to smoke, and soon there fall out of the bore-hole red-hot sparks which kindle the dry leaves laid around. The man assists by blowing at the sparks. Twigs and branches, which are now quickly collected, are not broken in the manner usual with us - across the knees - but always across their hard skull, the bone of which is so thick that they can easily break branches one and a half to two inches in diameter. The natives usually carry with them the two pieces of wood for kindling fire as long as they are serviceable. I tried to use them, but succeeded only in producing smoke.

Whenever the Australians rest they build a fire, though it be ever so warm, and at all times of the day, partly for comfort, partly in order to roast the provisions which they may have found. On short expeditions they usually make the women carry a fire-brand with them, finding this more convenient than to use the apparatus above described. They always have fire in front of their huts, but usually a small one, no doubt to avoid attracting the attention of hostile tribes.

As we were encamped round the fire I, feeling icy cold in my wet clothes, could not help envying the naked blacks who, independent of garments, became warm and good-humoured in a few minutes. But in a short time they were as cold as ever, for we had to proceed on our journey in the ceaseless rain. Now and then they exclaimed with a sigh, Takolgoro ngipa I - that is. Poor me! - and we had to halt, so that they might warm themselves again, and soon they were once more merry and happy.

The rain had ceased when, late in the evening, we returned to our camp. The natives were hungry, and were determined to hinder me from taking my usual bath, striking their stomachs impatiently, and crying, Ammeri! ammeri! - that is, Hungry ! hungry ! I threatened them with my revolver, as I did not wish to be cheated out of my only pleasure for the day, so they became quiet, and I took a refreshing bath in the clear water of a mountain brook.

I always began the day before sunrise, and after making the necessary preparations for the excursion, I rambled about with the blacks all day long, frequently without eating. Marching through the dense scrubs is very exhausting, the hot climate makes one weak, and it requires much effort to maintain one's good-humour and courage and at the same time to stimulate the indolent natives to do their work. Add to this that it is constantly necessary to be on one's guard against attacks, and it will be evident that I needed a few moments' respite; and in order to preserve my health and vigour I availed myself of the opportunity of taking a bath in the nearest pond or brook.

After refreshing myself in this manner I had to be cook both for myself and my greedy companions. Fortunately I did not that evening have to prepare the animals I had shot, for the weather was so cool after the rain that they would keep overnight.

On the way home to Herbert Vale we passed the forests of gum-trees which clothe the base of the mountain range. Here is the favourite resort of the bees, and my blacks at once began to look for their hives, for honey is a highly valued food of the natives, and is eaten in great quantities. Strange to say, they refuse the larvae, however hungry they may be. The wax is used as a glue in the making of various implements, and also serves as a pomade for dressing the hair for their dances and festivals. The Australian bee is not so large as our house-fly, and deposits its honey in hollow trees, the hives sometimes being high up. While passing through the woods the blacks, whose eyes are very keen, can discover the little bees in the clear air as the latter are flying thirty yards high to and from the little hole which leads into their storehouse. When the natives ramble about in the woods they continually pay attention to the bees, and when I met blacks in the forests they were as a rule :gazing up in the trees. Although my eyesight, according to the statement of an oculist, is twice as keen as that of a normal eye, it was usually impossible for me to discover the bees, even after the blacks had indicated to me where they were. The blacks also have a great advantage over the white man, owing to the fact that the sun does not dazzle their eyes to so great an extent. One day I discovered a small swarm about four yards up from the ground, and thereby greatly astonished my men. One expressed his joy by rolling in the grass, the others shouted aloud their surprise that a white man could find honey.

It is an amusing sight to observe the natives gathering honey. One of them will climb the tree and cut a hole large enough to put his arm through, whereupon he takes out one piece after another of the honeycombs, and as a rule does not neglect to put a morsel or two of the sweet food into his mouth. He drops the pieces down to his comrades, who stand below and catch them in their hands. At the same time the bees swarm round him like a black cloud, but without annoying him to any great extent, for these bees do not sting, they only bite a little.

Most of the honey is consumed on the spot, but part of it is taken to the camp, being transported in baskets specially made for this purpose. These baskets are of the same form as the other baskets made by the natives, but more solid and smaller in size ; they are made of bark, so closely joined with wax that they will hold water. Sometimes the honey is carried a short distance on a piece of bark, a border of fine chewed grass being laid round the edges in order to keep it from running off. Sometimes also a palm leaf is used, which is folded and tied at both ends, so that it looks like a trough. It is the same kind of trough as the natives use for carrying water, and can be made in a few minutes.

In almost every hive some old honey is to be found which has fermented and become sour, because these bees, which have only rudimentary stings, are not in possession of any poison to preserve it with. It must also be noted as a remarkable fact that this honey yielded by the poison-less bees never quite agreed with me; it used to give me, nay even the natives, diarrhoea, while on the other hand I can enjoy any quantity of European honey with perfect comfort. The old honey, which the bees do not eat themselves, looks like soft yellow cheese, and the civilised blacks call it old-man-sugar-bag. The blacks do not reject it, but mix it with fresh honey and water in the troughs just described. Fresh honey is also sometimes mixed with water.

This mixture of honey and water is not drunk, as one would suppose, but is consumed in a peculiar manner. The blacks take a little fine grass and chew it, thus making a tuft which they dip in the trough and from which they suck the honey as from a sponge. While they eat they sit crouching round the trough, and as each one tries to get as much as possible, the contents quickly disappear. Where spoons are wanting this would seem a natural and practical invention, and is surely calculated to secure an equitable division of the honey, as in this way it is difficult for any one person to get more than his share. After the meal the tufts are placed in the basket, where they are carried as long as they are fit for use.

The Australian wild honey, which is of a dark brown colour, is hardly equal to the best European. Its aroma is too pungent, and its flavour is not so delicate. In the trunks of the trees it keeps cool even when the weather is very hot, and supplies a healthy, pleasant food; but I could not, like the natives, make a meal of it. I soon grew tired of it, although it now and then formed an agreeable change in my simple bill of fare, and was to some extent a substitute for sugar. In the large scrubs we never found honey.

When I reached Herbert Vale the mail had just arrived. It was a real festival when the postman, twice a month, passed the station and brought us news from the outside world. He was in the habit of spending the night here on his way up to the tableland, where there were some stations. Armed with a revolver or a rifle, a postman must often ride 300 miles to deliver the mail.

Sometimes in an evening the Kanaka and I would sit together at the hearth and listen to the postman's stories and news from the civilised world. He was a man of varied experience, and a fine specimen of the so-called rough men, who are not, however, always so repulsive as the name would imply. The horse was not to be found that he could not ride; or, as he expressed himself, "I can ride any beast that has got hair on." He was a reckless fellow, utterly indifferent, always cool and self-possessed, and he shrank from nothing. He cared not what he ate so that he got food, and whether it rained or shone was a matter of supreme indifference to him.

Born in Victoria, he had been obliged to leave that colony on account of some of his youthful exploits, and had come to these uncivilised regions of the north, but ere long his admiration for the fair sex was transferred to the sable beauties of the forest, and for this very reason he had accepted employment in these wilds of the blacks. Upon the whole he was a good-natured fellow, and a type of the working class among the white men of Australia. They are reliable, correct in their habits, and attentive to their duties, open-handed, but reckless and unrestrained in their associations. "I care for nobody, and nobody cares for me" is their motto.

At the station I met another "rough man," less chivalrous than the postman, and his revolver rested less firmly in his belt. He had encamped close by, and expected to make money by catching living cassowary young for the zoological gardens. He also looked for a kind of palm, which he claimed would make splendid billiard cues. Supplied with tobacco and coloured handkerchiefs as a means of paying the blacks, he made a number of fruitless excursions.

I happened to tell him that I had been present at a borboby, and this aroused his desire to witness the next one, which was to take place in a few days. He did not want me to be the only white man who had seen such a contest, and got the Kanaka to show him the way up there. But both were obliged to save their lives by flight, the blacks having surrounded them, shouting, Talgoro, talgoro! - that is, Human flesh, human flesh!

Willy, one of the blacks who sometimes came to the station, had noticed that I had both meat and tobacco, and one day expressed a desire to accompany me. He said, "Go with me to my land, and you shall get both yarri and boongary," Willy's land is not far from Herbert Vale, and his mountain tribe was on friendly terms with many of the blacks of Herbert River; but still, being a border tribe, it was on an unfriendly footing with others. As I was fairly well acquainted with Willy, and had some confidence in him, I resolved to visit this region which he praised in such high terms.