Kamin (implement for climbing) - On top of the gum-trees - Hunting the wallaby - The spear of the natives - Bird life in the open country - Jungle-hens - Cassowary.

A few days after my arrival at Herbert Vale, the natives were to undertake a hunt of the wallaby, and with two black companions I presented myself at the place where the hunt was to begin. We left home in the morning. The forenoon was devoted to hunting for small mammals, which during the daytime keep themselves concealed in the high trees. With kind words and tobacco I induced my blacks to climb up one immense gum-tree after the other.

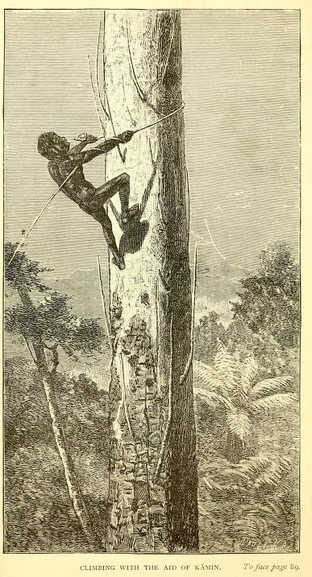

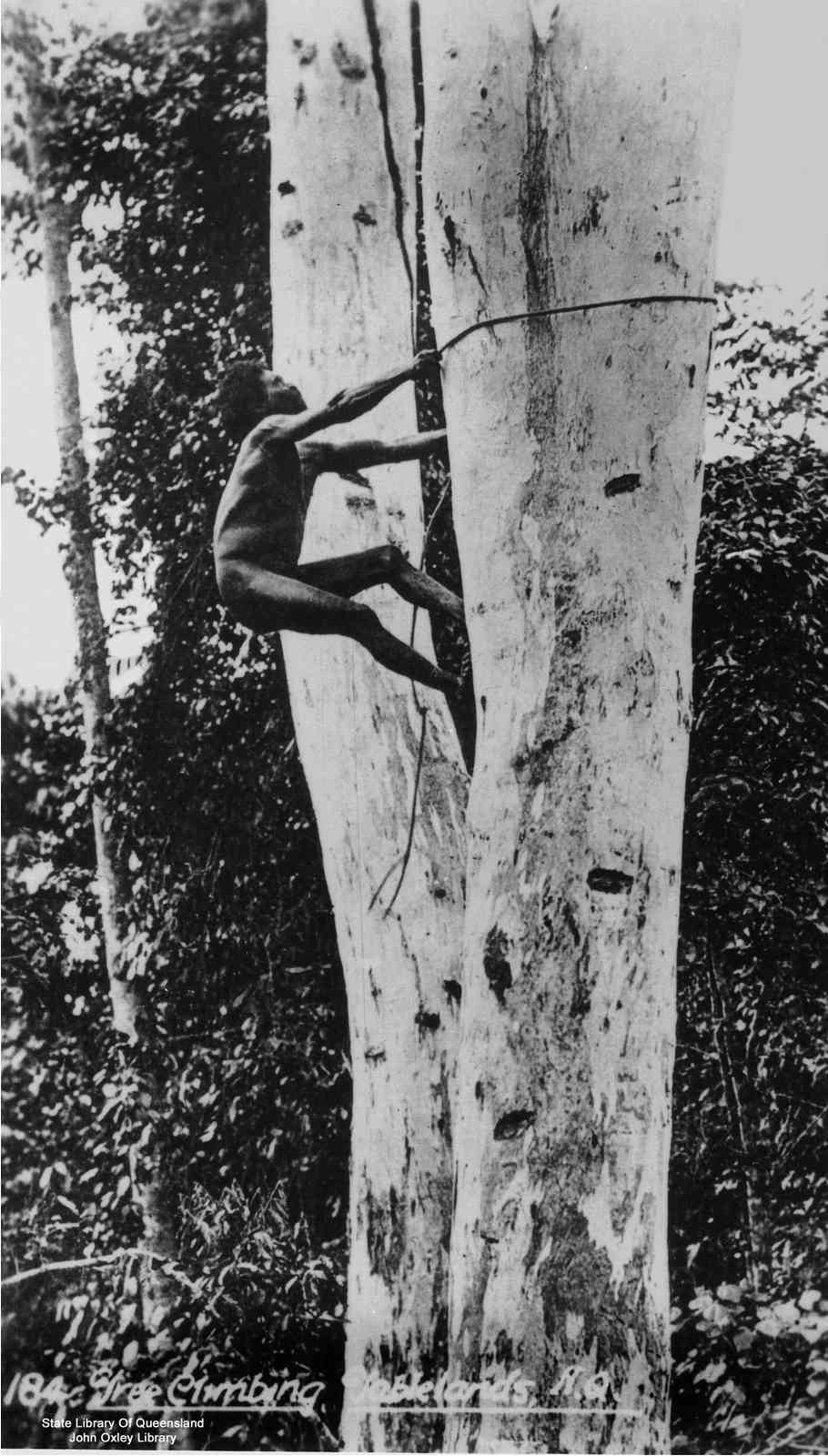

The Australian black on the Herbert River was more skilful in climbing than any of the other natives I had seen up to this time. If he has to climb a high tree, he first goes into the scrub to fetch a piece of the Australian calamus (Calamus australis), which he partly bites, partly breaks off; he first bites on one side and breaks it down, then on the other side and breaks it upwards - one, two, three, and this tough whip is severed. At one end of it he makes a knot, the other he leaves as it is. This implement, which is usually sixteen to eighteen feet long, is called a kamin.

After wiping his hands in the grass so as to remove all moisture from perspiration, he takes the knot in his left hand, throws the kamin around the big tree-trunk, and tries to catch the other end with his right hand. When, after a couple of abortive efforts, he has succeeded in this, he winds this end a few times around the right arm and thus gets a secure hold. The right foot is planted against the tree, the arms are extended directly in front of him, the body is bent back, so that it is kept as far as possible away from the tree, and then the ascent begins. He keeps throwing the kamin up the tree, and at the same time he himself ascends about as easily as a sailor uses an accommodation ladder, but as climbing by means of the kamin is of course much harder work, he is compelled to stop every few moments to take breath. When he has reached the branches of the tree he hangs the kamin on one of them, while he examines the holes in the trunk.

It seemed to me that he laced his kamin so carelessly that it might easily fall down while he was engaged in the hunt for animals in the tree. If this should happen, I hardly know how he could get down those high and smooth trees. But with the aid of the kamin it is easy enough. He walks down backwards very rapidly. If it is a very large tree, and the bark very smooth, he chops niches in it for his big toe. He takes his tomahawk in his mouth, and when he wants to use it removes the kamin from his right arm and winds it around his right thigh, whereupon with his free hand he cuts the next niche or two in the bark of the tree.

Thus we see the importance of having a knot in one end of the kamin and none in the other. This arrangement has also another advantage, that the kamin can be used in a tree of unequal thickness, and in different trees; for the native usually carries this implement with him and uses it in a number of trees. Instead of rolling it together, or winding it into a coil, he draws it behind him, simply holding on to the knotted end. Strange to say, this is the most practical way of carrying it, for the kamin is hard and smooth, so that it never sticks fast in the brushwood. Rolled into a ring it would doubtless be a great source of trouble in the dense scrub. No tree is too high or too smooth for the Australian native to climb, provided its circumference is not too great.

But my blacks climbed the high gum-trees in vain. They did not succeed in discovering a single opossum, flying-squirrel, or any other nocturnal animal that hides in tree-trunks. The reason for this, in the opinion of the blacks, was a circumstance unknown to me, viz. that both the opossum and the flying-squirrel disappear in the summer time and do not return before the rainy season, at which time they are abundant. At first I had grave doubts in regard to this explanation, and made my natives climb a number of trees, but as I did not find a single specimen, I came to the conclusion that they were right. The opossum (Irichosurus vulpecula) and the flying-squirrel leave the bottom of the valley in the summer. I do not know what becomes of the former, but I found Petauroides volans and several species of Petaurus in the middle of the summer on the open grass plains in the mountain regions near Herbert Vale. In the rainy season the opossum and the flying-squirrels were very numerous about the station.

Late in the afternoon I arrived with my companions at the spot where the wallaby hunt was to take place. It was a large plain, surrounded on all sides by scrub and overgrown with high dense grass. The wallabies (Macropus agilis) are very numerous in the Herbert river bottoms, but keep themselves concealed during the day. The usual way of hunting these animals is by setting fire to the grass; this starts them up and they try to escape. The natives stand on guard ready to attack the flying animals, and try to kill them with spears while they, fleet as the wind, run by. As a rule the hunt is postponed until the afternoon, for there is so much dew in the morning that the grass looks as if there had been a shower of rain; but after noon it is quite dry again.

I looked in vain for my black hunting companions, but soon discovered that they were just crossing the river, which flowed among the scrubs below the plain. I rode to the bank and discovered one group after the other coming into view behind the trees on the other side, the women peeping curiously from behind the bushes to catch a glimpse of the white man. They looked timid, and deemed it safest to cross the river higher up, where they came over each with her children on her shoulders and a basket on her back. Some of them had fire with them, carrying burning sticks in their hands. The men waded across at the place where I stood. It interested me to watch them in their natural nakedness as they gradually gathered around me on the bank of the river, but as usual it was necessary to be watchful of the long spears which they bore.

They soon separated, some of them stationing themselves on the outside of the field, while the rest remained to set fire to the grass. Jacky, one of my blacks, indicated to me that for the sake of the horse I had better remain where I was. He himself went with the other men, and took his station on the side of the field. Soon those who had remained behind spread themselves out, set fire to the grass simultaneously at different points, and then quickly joined the rest. The dry grass rapidly blazed up, tongues of fire licked the air, dense clouds of smoke rose, and the whole landscape was soon enveloped as in a fog.

I fastened up my horse and went into this semi-darkness, watching the blacks, who ran about like shadows, casting their spears after the animals that fled from the flames. But though many spears whizzed through the air, and though a large field was burned, not a single wallaby was slain.

The Australians have the reputation of being able to hurl the spear skilfully ; they do much damage to the white man's cattle, and many a white man is killed by this weapon; but, strange to say, I have never observed any remarkable skill in its use among the blacks of Herbert river.

This may be explained by the fact that in a great measure they find their food in the scrubs, where spears cannot be used. Of course it is difficult to hit an animal running at full speed, but I have often seen them miss sitting shots. On the other hand, it sometimes happens that they kill three or four during a hunt.

This time all the booty consisted of a few bandicoots (Peramelidae), which were dug out of the ground between the roots of a large gum tree. While the men were busy doing this the women stood ready to receive the game and take it home. The bandicoots are good eating even for Europeans, and in my opinion are the only Australian mammals fit to eat. They resemble pigs, and the flesh tastes somewhat like pork.

During the whole chase the women took the greatest delight in watching the sport of the men. At the same time they were busily occupied in pulling up the roots of acacias, inside which a larva (Eurynassa australis) is concealed, which is eagerly sought after, and is regarded by the natives as a most delicate morsel. The larva when found was immediately roasted in the red-hot ashes lying everywhere on the ground, and was at once devoured.

On grassy plains the hunt of the wallaby, which is the sport most dear to the men, is always carried on in the manner above described, that is, by burning the grass or simply by wandering about hunting for the sleeping animals. The wallabies have excellent ears, and start at the least noise. They may sit for a few moments moving their large ears to catch any suspicious sound; but, as a rule, even the catlike steps of the blacks are too noisy to enable them to approach sufficiently near the wallaby. When it rains they do not hear so well, and it is then easier to kill them.

These wallabies, the large kangaroos, and the white man's cattle are the only animals which the blacks near Herbert Vale kill with their spears, though the latter are their most important weapons. The spear, usually eight to ten feet long, consists of two parts - the front, which is sharp-pointed, made of a heavy hard kind of wood, and the butt end, which is usually the longer of the two, of Xanthorrhaea or a similar light material. These two parts are joined and bound together with wood fibres, or with sinews of the kangaroo's tail, and beeswax heated over the fire. The point is never envenomed, as they know little or nothing about poison. Nor is there any flint point attached, as is often the case in Australia. In Northern Queensland I have occasionally seen the point of the spear furnished with a barb of fish bones for a length of one or two feet up the spear. Such javelins were thicker and shorter than the common ones and were used only for fishing.

The spear is thrown with the help of a throwing stick, which is equal to a quarter or a fifth part of the whole length of the weapon, and has a hook at one end made of wood, likewise fastened with beeswax and fibres of wood or the sinews of the kangaroo's tail. This hook is attached to the butt end of the spear, which has a socket fitting the hook. Thus the stick lies along the under side of the spear. When the latter is to be thrown, the stick and the weapon itself are seized with the first three fingers. Both are carried back as far as possible, and the spear is thrown with the force of a sling.

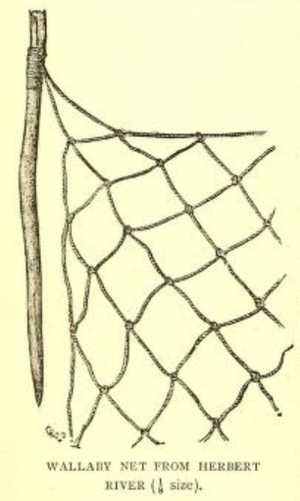

In the wallaby chase the blacks on Herbert river also use nets with large meshes, placing them in a line between posts to which they are fastened. Such a net is fifteen to twenty feet long, and the meshes are about four inches each way.

The chase took place in the so-called open country on Herbert river, which, to the superficial observer, does not differ in any striking manner from that of Southern Queensland. The high gum trees are found here, but the country is more fertile, and the grass is so high that it is difficult to get through it. On this moist soil grow whole forests of the screw palm (Pandanus). The country altogether does not look so dry as farther south; small swamps exist here and there, and brooks often cross one's path.

I found fewer birds in this open country than I used to see elsewhere in Australia. Nor did I ever meet in the bottoms of Herbert river valley with those birds which seem to belong inseparably to an Australian forest landscape, such as the piping crow (Gymnorhina tibicen), the butcher-bird (Cracticus nigrogularis), or the Australian wagtail (Grallina picata). Parrots were also scarce, but in the scrubs up the mountains I saw plenty of them. The bird Centropus which is common in all Queensland, is found here in great numbers. Although it really is a cuckoo, the colonists call it the "swamp pheasant," because it has a tail like a pheasant. It is a very remarkable bird, with stiff feathers, and flies with difficulty on account of its small wings. The "swamp pheasant" has not the family weakness of the cuckoo, for it does not lay its eggs in the nests of other birds. It has a peculiar clucking voice, which reminds one of the sound produced when water is poured from a bottle - a sound familiar to all who have camped beneath the gum-trees of Australia.

The open country was therefore not the best territory for me, for there was but little game. On the other hand I reaped a more abundant harvest in the scrubs, where there is a greater variety of animal life; and to wander with the blacks in these almost impenetrable jungles in the wide river valley was very interesting. Nothing escapes their notice. On one occasion, in the middle of September, when I made an excursion with one of them, he made me understand that he wished to go away for a moment to look for something. Time passed, and I became impatient, but when I began to shout for him I was not a little surprised to hear his response coming from the far distance above. Approaching, I discovered him in the top of an immensely high tree. He threw down to me two large young of the gigantic wader Jabiru (Mycteria australis). Quickly, and with the dexterity of an acrobat, he descended, laying hold with his hands of the twining plants which hung like natural ropes down the trunk of the tree.

It is not easy to penetrate this scrub, which is so dense that one has scarcely elbow-room; but along the rivers there is more breathing space. Here beautiful landscapes are often disclosed to view; the most varied trees vie with each other for a place along the quiet stream; while creeping and twining plants hang in beautiful festoons over the water.

On first entering the scrub, the solemn quiet and solitude which reign there are striking. You work your way through it by the sweat of your brow; you startle a bird, which at once disappears, and your prevailing impression is that there is no life. But if you come there in the early morning or towards evening, and sit down quietly, it is surprising to see the birds approaching gently, as if they had been called, and disappearing as noiselessly as they came. Silence as a rule reigns in the scrubs, and the song of birds is rarely heard; though the doves coo in the evening, and sometimes the melancholy note of the jungle-hen is to be heard, or even, if you are lucky, the thundering voice of the cassowary.

One of the first birds you notice is the cat bird (Aeluroedus maculosus), which makes its appearance towards evening, and has a voice strikingly like the mewing of a cat. The elegant metallic-looking "glossy starlings" (Callornis metallica) greedily swoop with a horrible shriek upon the fruit of the Australian cardamom1 tree. The ingenious nests of this bird were found in the scrubs near Herbert Vale - a great many in the same tree. Although this bird is a starling, the colonists call it "weaver-bird."

1This is a fictitious name, as are the names of many Australian plants and animals. The tree belongs to the nutmeg family, and its real name is Myristica insipida. The name owes its existence to the similarity of the fruit to the real cardamom. But the fruit of the myristica has not so strong and pleasant an odour as the real cardamom, and hence the tree is called insipida.

There are few birds that look better in the green tree-tops than the Torres Strait pigeons (Carpophaga spilorrhoa) which is white, like a ptarmigan in winter dress, with the exception of its wings and tail, which are black. In November a pair of them built their nest in a high tree near the scrub, and like several other varieties of birds, had just arrived from the northernmost part of Queensland and New Guinea; for it was now spring, and all the birds that migrate northward in the winter had returned, such as the celebrated Australian giant cuckoos (Scythrops novae-hollandiae), whose terrible shrieks are heard at a great distance when in scores they gorge themselves in the large fig-trees. On the banks of a stream I shot a specimen of the very small kingfisher (Ceyx pusilla), which belongs to New Guinea and Northern Australia. It was the only specimen I saw on Herbert river. The racket-tail kingfisher (Tanysiptera)- has also been shot in the scrubs here.

But what especially gives life and character to these woods are the jungle-hens (mound-builders), which I have already mentioned. The weird, melancholy cry of these birds once heard is not easily forgotten; at sunset and in the twilight of the evening it is in perfect harmony with the stillness and repose of nature. The bird is of a brownish hue, with yellow legs and immensely large feet; hence its name Megapodius. It is very shy, and therefore it is not easy to get a glimpse of it, but its remarkable nests, which are formed of large heaps of earth and decayed leaves, like those of the talegalla, are frequently to be found in the scrubs. From my own experience I venture to assert that the mounds of the jungle-hen are larger than those of the talegalla. For many years they were thought to be the burying-grounds of the natives, says Mr. Eden, who mentions one which was sixteen feet high and sixty-two feet in circumference at the base. One would hardly think that birds could build so large a mound.

In these scrubs the proud cassowary, the stateliest bird of Australia, is also to be found. I had already made several vain attempts to secure a specimen of this beautiful and comparatively rare creature. We had frequently seen traces of it under the large fig-trees, the fruit of which it eats. The excrement of the cassowary looks more like that of a horse than of a bird, and I saw large heaps under the fig-trees. We often approached without seeing it, for it is exceedingly shy and departs on the slightest noise, consequently it is very difficult to get a shot.

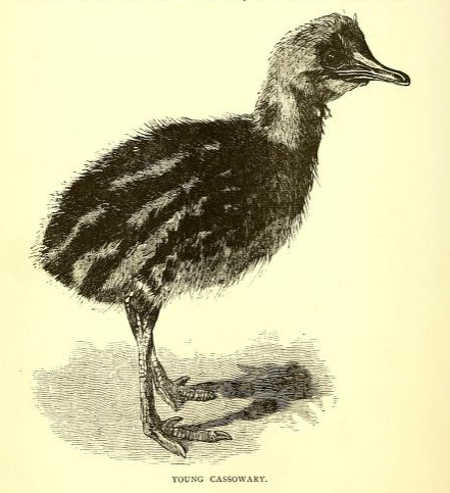

On October 6 the natives brought me two eggs and a young bird just hatched. I at once requested one of them to guide me to the nest, whither I took it, hoping thereby to attract the old bird. Near the nest, which was formed of a not very soft bed of loose leaves massed together, we placed the young one and then stepped aside to see what would happen. It first began to run after us, but as it soon lost sight of us, commenced to cry violently. After a lapse of about ten minutes we suddenly heard the voice of the cassowary, which usually sounds like thunder in the distance, but now, when calling its young, it reminded us of the lowing of a cow to its calf The sound came nearer and nearer, and soon the beautiful blue and red neck of the bird appeared among the trees, and its black body became visible. It stopped and scanned its surroundings carefully in the dense scrub, but a charge of No. 3 shot, fired from a distance of fifteen paces, laid it low.

My black companion gave a shout of victory, and ran back to the camp to get some men to carry the precious burden home. Six natives took turns in carrying it to the station, where I at once set to work skinning it. The blacks made a feast of its flesh, and the skin formed a valuable addition to my collection. It was an unusually fine specimen of a male, who thus appears to care for the young, at least in the early stage. The eggs, three1 in number, are frequently laid at long intervals. In this instance there was a bird just hatched, an egg almost hatched, and another egg the contents of which could easily be blown out. Thus we see that the young are not hatched at the same time, and that the male must therefore care for them while the female is busy brooding. After the third egg is hatched, the male and female probably share the burden of supporting the family.

1 The colour, which is a light green, varies in shade in the three eggs.

The first specimen of this variety of cassowary (Casuarius australis) was shot in these same scrubs near the close of the sixties.

Its eyes, which cannot fail to be admired, form the most beautiful feature of the cassowary. Their expression is defiant and proud, as that of the eagle's eyes. The natives hunt the bird with the aid of their dingoes, which are able to kill the half- grown and sometimes even the old birds. The flesh tastes very much like beef, and is very fat. In the rainy season the cassowary is sometimes compelled to take to the water, and proves itself to be a good swimmer.

The blacks claim that their hands become white if washed in the contents of its stomach at the season of the year when it mainly feeds on a fruit which they call tobola. I give this for what it is worth; but I have seen natives having on their hands white spots which they insisted were produced in this manner; no doubt these spots were nothing more than vitiligo or leucopathia acguisita, found among all races of men.