Arrival of the native police - The murderer caught - Examination - Jimmy is taken to Cardwell - Flight of the prisoner - The officer of the law - Expedition to the Valley of Lagoons - A mother eats her own child - My authority receives a shock.

When I arrived at the station I talked with the natives about the event. They seemed to be surprised, but observing that I knew all about the matter, they found there was no use of assuming ignorance, and they began to converse with me about the murder as a matter well known to them. Thus I secured all the details in regard to this horrible affair. But they held it perfectly proper for Jimmy to kill the white man who was unwilling to share his food with him. I made them understand that this was not my view, and threatened to send for the police. This threat I would also have carried out, had not, three days later, a sergeant of the native police, with a few troopers, accidentally come and encamped at Herbert Vale. He had been in Cardwell to fetch provisions and liquor for his chief, who lived on the tableland.

When the blacks saw the police their memory again failed them. It was no longer Jimmy who had murdered the white man, but two other blacks, Kamera and Boko. In a certain sense this was true, for a year and a half previously they had actually murdered a white man. It was thought that he had been eaten by a crocodile, and now for the first time it was discovered that a murder had been committed, but this man was not Jimmy's victim. By confusing the two events, they tried to draw attention away from Jimmy. For Kamera and Boko they cared less, they being strangers, but Jimmy belonged to their own tribe and must be saved.

The boldest and most experienced of these "civilised" natives therefore sought to make friends with the police. They brought them their best women, carried wood and water for them, and tried to serve them in every way. I told the police sergeant what had happened, and requested him to arrest Jimmy, who could be found at a great borboby which was to be celebrated just at this time two or three miles from Herbert Vale.

The next day the sergeant went to the borboby to arrest him, taking with him three of the blacks at the station, and also the Kanaka, in order that they might identify Jimmy.

While he was absent, the postman came from Cardwell. When he learned what had happened, he remembered that he several times had felt a bad smell where the murder was supposed to have taken place - that is, near Dalrymple Creek.

We now hoped that the sergeant would bring the murderer in the evening, but he returned without the prisoner. Three persons called Jimmy had been shown to him, and they all denied having perpetrated the murder. The natives who had gone with the sergeant to the borboby had declared that the right Jimmy was not there. I knew this to be not true, and so I requested the sergeant to make another effort. The Kanaka told me that the right Jimmy really was there, and that it had vexed him to see that the sergeant would not arrest him. The sergeant had given all his attention to the fair sex, and had taken no interest in finding Jimmy.

As I insisted that the murderer should be arrested, the sergeant started off early the next morning, again in company with the Kanaka. He now took with him two of his own men and handcuffs for the culprit. In a few hours they returned with the prisoner, and I was sent for. It was Jimmy. He was handcuffed; his suspicious face was restless, the blood rose to his face, and if a black man can be said to blush, then Jimmy did so now.

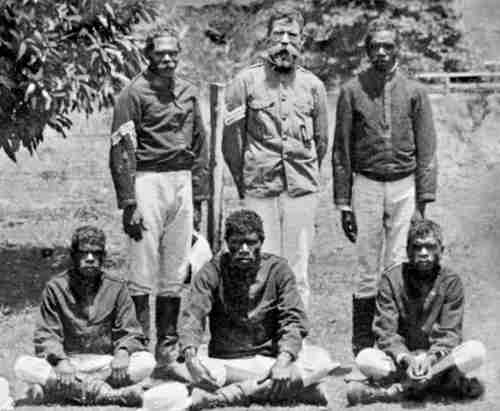

Under the storehouse, which stood on high posts, there was a large room surrounded by a lattice. Here the court was held. The prisoner was brought in by two of the troopers, and the examination began. The persons present were the sergeant, the old keeper of the station, the postman, the Kanaka, and I. The blacks stood outside the gate and watched the whole proceeding with the greatest interest.

The sergeant, a tall powerful man, who was the representative of the law there, began the trial by snatching a throwing-stick from one of those standing outside and striking Jimmy on the head with it, in order to force him in this brutal manner to tell the truth.

"You have killed the white man," he kept repeating, and added new weight to his words by inflicting fresh blows; but the criminal denied everything, while he tried to protect himself with his fettered hands.

"You have killed your wife," shrieked the sergeant; but Jimmy made no answer to this charge, he simply tried to ward off the hard blows he was getting. Suddenly the sergeant broke the stick over Jimmy's head, which fortunately ended this inquisitorial part of the trial. The sergeant, who in the meantime had become heated by his exertions, then turned and said in a faint voice: " There is no doubt that he is the culprit, but let us now hear what the blacks have to say."

One or two of them were called in, and made the same statements as Jimmy, insisting that he had not killed the white man, but they all testified unanimously that he had murdered his wife, Molle-Molle. As she was a woman, they saw no peril in making this admission. Jimmy, too, confessed this crime.

"That is quite sufficient," muttered old Walters.

"Take him down to the river and wipe him out," said the sergeant to his men.

"And throw him into the water, then there will be no smell," added the postman.

In a hesitating manner the troopers began to execute the order of their stern master. One of them, David, suggested that the prisoner ought first to show the body of the dead man, a pretext for getting the matter postponed and thus saving Jimmy's life, for the police were anxious to do him and his friends a service in return for the women they had sent as a bribe.

Meanwhile the sergeant gave orders that they should bring the culprit to the camp and make short work of it.

When Jimmy discovered that the sergeant was in earnest he became literally pale, and went with them as one having no will of his own. The natives, who at first were utterly perplexed, followed slowly and silently.

The keeper of the station had during the trial suggested that the matter ought not to be reported to any white man. The fact is, the police had no authority to carry out the sergeant's severe orders. I found upon investigation that, no matter how clearly the murder is established, the English law does not permit the shooting of a criminal in this manner without a regular procedure. The prisoner had not confessed the murder, nor, as was remarked by David, had the corpse been produced. I was anxious that the proceedings should be in all respects regular and legal I therefore at once went down to the camp and explained my doubts in the matter to the sergeant.

Here all was quiet. The police were taking things easy, and the prisoner, who had received something to eat, seemed very comfortable.

The sergeant informed me that the prisoner had now made a full confession. When he got sight of the guns he became very communicative, and had given a number of details. He had attacked the white man at Dalrymple Creek, had given him a blow with his axe on the back of the head, and had thrown his body into the water. He was also willing to show the place where he had committed the murder.

I suggested to the sergeant that Jimmy should be taken to the Cardwell police court, which was the proper court to decide this matter. On the way thither the prisoner might show the body of the dead man. The sergeant considered my suggestion to be very proper, and not thinking himself particularly qualified to make a written statement to the authorities, he left it to me to prepare the written report.

Jimmy rode a horse between David and another policeman. The handcuffs were taken off, put on his ankles, and fastened to the stirrups. All this surprised me, but I said nothing, as I supposed they knew best what was necessary. In my letter to the police magistrate in Cardwell I informed him that the prisoner had confessed the murder and was willing to go and point out the body of his victim. The police were to travel the whole night, and might be expected back in the evening of the next day.

The sergeant now relapsed into a most astonishing dolce far niente. He went into his tent and began to drink the rum that belonged to his chief, and for the sake of convenience he had set the jug by the side of his bed.

Early the next morning I was greatly surprised at meeting David, who handed me back the letter I had written, and told me they had had the misfortune to lose the prisoner. On their arrival at Dalrymple Creek, Jimmy had shown them the dead body in the creek, then he suddenly severed the stirrup straps and fled with the irons on his feet. The night was dark, and it was raining, so that it was easy for him to escape, although the police fired some shots after him.

This information was a great disappointment to me, but it had an opposite effect on the natives, who assured me that Jimmy would break the irons with stones and thus free himself from them. I could not help suspecting that David had been in collusion with the natives and given aid to the prisoner, and I did not conceal the fact that I was greatly displeased. Meanwhile it was impossible to discuss the matter with the sergeant. He was dead drunk in his tent, and continued in this condition for four days and nights. Now and then he became conscious, but then he would take another drink, and perhaps request some one to fan him with the tent door. Once or twice a day he would take a little walk round the tent, supporting himself on two of the troopers, who almost had to carry him. The condition of affairs kept growing worse. The troopers availed themselves of this opportunity to help themselves from the jug, and they even gave the natives grog, or "gorrogo" as they called it.

In this manner the sergeant maintained the law in the eyes of the natives, and in this manner he preserved discipline among his subordinates. What an impression this would leave among the blacks in regard to right and wrong! When sober, he was in the habit of saying that "the only way of civilising a black-fellow is to give him a bullet."

I sent a letter to Mr. Stafford, the sergeant's superior officer, who lived in the police barracks on the tableland. I gave him an account of what had happened, and demanded the punishment of Jimmy for the two murders he had committed. I added that, if nothing was done in the matter, I would make a full report to the Government.

After putting my collections away in good order at my headquarters, I got myself ready to depart for the Valley of Lagoons, where I intended to pass the worst part of the rainy season. During the last days my collection was augmented by the addition of two most interesting specimens of the Australian fauna. The one was a pouched mouse (Sminthopsis virginiae), which is tolerably abundant in the Herbert River valley. It burrows in the earth and is dug up by the natives, who are fond of its flesh. The specimen I secured is the only one to be found in museums. From a complete description by De Tarragon in 1847 it is evident that he found the same animal, but his specimen has been lost.

Under very peculiar circumstances I also secured a young talegalla, which the Kanaka had obtained from the blacks. It was in fact intended for the sergeant, but he had requested the Kanaka to keep it for him. The animal was placed under a kettle on the bare ground in the kitchen, where it spent six days without food. The Kanaka informed me that the talegalla was in his keeping, and offered it to me, since its rightful owner was in no condition to take care of it. The poor creature had tried to maintain life by scratching the hard ground, where no food was to be found, and still it was in erfectly good condition. The blacks had taken it out of the nest while they were digging for eggs, and when found it was not more than one or two days old.

Near the end of February I said good-bye to Herbert Vale for a time, and was glad to get away from the annoyances I had had during the latter part of my sojourn there. My relations with the blacks had become more complicated, for they had noticed that I was the only one who insisted on the punishment of Jimmy, and they saw that my efforts were frustrated. They had for the time being lost their respect for me, but I had hopes of re-establishing my authority when Mr. Stafford came down and made them fear the agents of the law. My safety demanded that severe measures should be taken, and I therefore made up my mind to try to meet him personally. He lived not far from Mr. Scott's station, the Valley of Lagoons.

The scenery is quite different on the table-land from that in the Herbert River valley, and consists of large green grassy fields extending far and wide, sometimes covered with tall forests of gum-trees. The heat and rainfall are considerably less, but still water is abundant, especially around the Valley of Lagoons, which has its beautiful name from the numerous fresh-water lakes found in that locality. At the station, situated on a high hill, there was always a cool refreshing breeze.

There are several indications that this region is gold-bearing, and some day we may hear of the discovery of large quantities of the precious metal. Near the station is a large district covered with lava, in which are many caverns serving as hiding-places for the savages, who are constantly at war with the white population. Rock-wallabies are fond of this lava district. I there shot the beautiful little bird Dicoeum hirundinaceum.

In Burdekin river, which is full of fish, I one day discovered an Ornithorhynchus anatinus swimming in the clear water.

A few days after my arrival I received a visit from Mr. Stafford, who expressed his regret that his men had acted so foolishly. As soon as he could get his horses shod, he would himself go down to Herbert Vale and "investigate the matter." He said nothing about calling the sergeant to account for his conduct, but seemed to be chiefly interested in a journey which he was about to make to Townsville.

The blacks in this vicinity were not to be trifled with. They had repeatedly surrounded the police barracks in the night, and there was constant danger of an attack. They were also dangerous enemies to Mr. Scott's cattle, and according to the statement of the overseer, they had killed thousands of them. Three blacks were servants at the station, and were therefore "civilised," but their life here had not had any visible influence on their morals. One of them, a woman, told me that her fellow-servant had given birth to three children, all of which had been killed. The mother had put an end to two of them herself, while the third had been permitted to live until it was big enough to be eaten. The one who told me the story had herself put her foot on the child's breast and crushed it to death; then both had eaten the child. This was told me as an everyday occurrence, and not at all as anything remarkable.

I remained only fourteen days at this station, and in the middle of March I was back at Herbert Vale. The keeper told me that Mr. Stafford had spent a night at the station and had proceeded to Cardwell without taking any step in regard to Jimmy. He might possibly give his attention to the matter on his return. Meanwhile the postman and a sergeant sent by the police court at Cardwell had found the body of the white man and buried it. Jimmy had grown very bold, and had made his camp only a mile and a half from Herbert Vale. Still, it would be difficult to capture him. I tried to induce the blacks to kill him, representing to them that in that event no one else would be shot, while, if they did not kill him, they might all have to suffer.

They did, in fact, seem to get frightened, and told me they would have him shot. Under all circumstances, they promised to deliver him up as soon as Mr. Stafford returned. Had the latter taken up the matter on his return, Jimmy would not have escaped his deserts. But Mr. Stafford was wholly indifferent. He spent the night at the station, and in the morning, as he was mounting his horse, he addressed a few words to one or two natives who happened to be present, and said, "You had better kill Jimmy yourselves." That was all he did in the matter.

My position was a perilous one, and my authority among the blacks had now received a new shock. The natives saw that they could take the life of a white man with impunity, and that Mr. Stafford was unwilling to pay any attention to my representations. From this they concluded that he was on their side, and that it would be safe to kill me. Even Jimmy felt secure. The next day he moved his camp nearer to Herbert Vale, and before long he visited the station itself. Still I never saw him. A few weeks later he broke into Mr. Gardiner's farm on the Lower Herbert and killed his dog.