A festival dance of the blacks - Their orchestra - A plain table - Yokkai wants to become a "white man" - Yokkai's confession - A dangerous situation - A family drama.

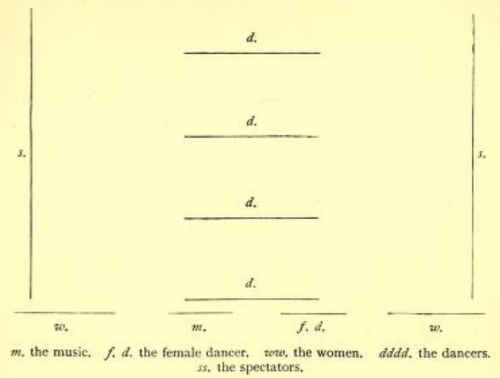

The next day, before sunset, the dance began again. At one end of the little place for dancing, where the grass had already been well trampled down, sat the orchestra, consisting, as usual, of only one, or sometimes of two men. The musician was sitting on the ground with his legs crossed, and was singing the new song, accompanying himself by beating together a boomerang and a nulla-nulla.

In front of him on the little plat of level ground fourteen to sixteen men were dancing in ranks of four or five each. Near the orchestra, on the right, a woman kept dancing up and down, keeping time with the men and with the music.

On Herbert river more than one woman never takes part in the dance. This is a great honour to her, and she is envied by all the other women, who sit in rows on both sides of her and the musician. They assume their favourite position and do not, like the men, cross their legs before them or sit on one of their hams, but they rest on their legs and heels, the legs being very close together. In this position they usually play an accompaniment to the music by beating both their open hands against their laps, thus producing a loud hollow sound.

The spectators sit on both sides of the dancers all the way up to the corners occupied by the women.

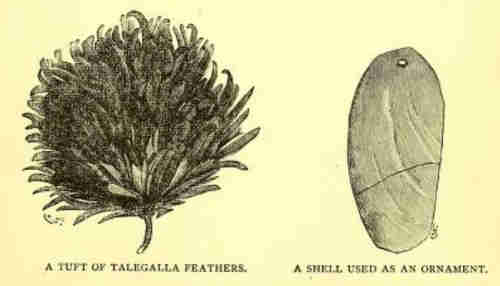

As a rule the spectators do not decorate themselves much for the occasion; one may be seen here and there who has painted himself with a little ochre borrowed from a comrade. The dancers, on the other hand, have done all in their power to beautify themselves. Their bodies shine with red, yellow, or white paint. Their hair is well filled with beeswax, and decorated with feathers, with the crests of cockatoos, and similar ornaments. For the purpose of giving themselves a savage look, some of them hold in their mouths tufts either of talegalla feathers or of yarn made from opossum hair. The latter kind of tufts or tassels the natives call itaka. Some of the natives have mussel-shells glued fast to their beards with wax. The Australian blacks and the Malayans are the only savages who employ this ornament in this manner.

Several of the women had painted themselves, some of them with alternating black and red bands across the face. Strange to say, the dombi-dombi (dancing-woman) wore no ornaments. She was middle-aged, with a pair of beautiful eyes, but her limbs were slender, and she had a large protruding stomach. The very uniform hopping movements of her lean body were not graceful. She kept her arms extended and spread the long slender fingers of her hands as far apart as possible. The sight of this woman jumping up and down in the same place, in the attitude above described, and with her large breasts dangling, was truly disgusting. But the woman seemed to enjoy herself wonderfully, and she was not relieved by any of the other women.

The chief attention centres on the male dancers, who are the heroes of the day. They start on the open side of the ground opposite the orchestra, and gradually approach the latter. Their twists and turns keep time with the music, and they continually give forth a grunting sound with accents in harmony with the music and their own movements. Near the orchestra they suddenly pause, scatter for a moment, and then begin again as before.

The music was quick and not very melancholy; the monotonous clattering, the hollow accompaniment of the women, the grunting and the heavy footfall of the men, reminded me, especially when I was some distance away from the scene, of a steam-engine at work.

While both the music and the song are an endless repetition of the same strophes, the dance has a few variations. Now and then a different figure is presented. One of those figures looked very well. Six men marched to the music in closed ranks, accompanying the rhythmical tramping of their feet with blows to the right and left with tomahawks and boomerangs. In other figures they presented a variety of comical movements, With arms akimbo, they spread their knees as far apart as possible, and jumped and grunted in time with the music.

The dance was utterly childish, but it interested me to observe that they had a somewhat different programme for each evening. They several times produced what might be called a pantomime, but, as I did not quite comprehend it, I cannot fully describe it. On the open side of the square, opposite the music, a sort of chamber was constructed, where the chief performers made their toilets and kept themselves concealed until the performance commenced. When it was time to begin the pantomime, they rushed forth, all more ornamented than usual with ochre spots of different colours over their whole bodies, and with false beards and hair made of fibres of wood. They took their places in line with the other dancers, and with the usual twists and turns and keeping time with the music, marched up to the orchestra, where they paused for a moment. Then they formed in two long lines, opposite each other, and two of the most gaudily decorated men stepped forth from the ranks. While the others remained standing in their places, these two kept running up and down along the ranks, acting like clowns, and making all sorts of ridiculous gestures. The most important part of their acting consisted in kneeling down opposite one another and putting a stick into the ground with the right hand, at the same time bending to one another with various kinds of gestures and grimaces. Thus they kept entertaining the spectators for a long time, and it must be admitted that these two natives gave evidence by their performances of no small amount of comic talent. The closing scene was vociferously applauded, and the charmed natives asked me if I, too, did not think the acting splendid. I could not induce them to explain to me the significance of the performance, but still I managed to find out that it had some connection with the devil.

The spectators now and then indicate their approbation by laughing aloud. The women sit with smiles on their lips, and take great pleasure in witnessing the performance. The female dancer also keeps her eyes constantly on the male dancers, but the musician at her side apparently takes no interest in what is going on. He sits there beating his wooden weapons together and singing with his hoarse but powerful tenor voice. He rarely looks up, as he has already been watching the exercises for weeks, and knows them all by heart; but even he sometimes seems to be amused. Now and then he raises his eyes and looks happy as a lark at the naked figures moving backwards and forwards in the strangest contortions. He never tires of singing, and whenever he begins the strophe anew he raises his voice with a sort of enthusiasm.

These festivals, called by the civilised blacks korroboree are of course evidence of friendly relations between the tribes. On this occasion the dance was given by several neighbouring tribes that were on friendly terms with each other. As a rule, however, the korroborees in Australia are given upon the settlement of wars and feuds among the tribes, and are a sort of ratification of the treaty of peace. Doubtless these festivals have, in the history of Australia, been of considerable importance in regard to the social development of the natives. The korroborees have facilitated bartering among them, and have also contributed toward promoting social intercourse among the tribes. It is a curious fact that these "ratifications of treaties of peace" frequently give rise to new feuds, on account of insults to women that are apt to occur at such festivals.

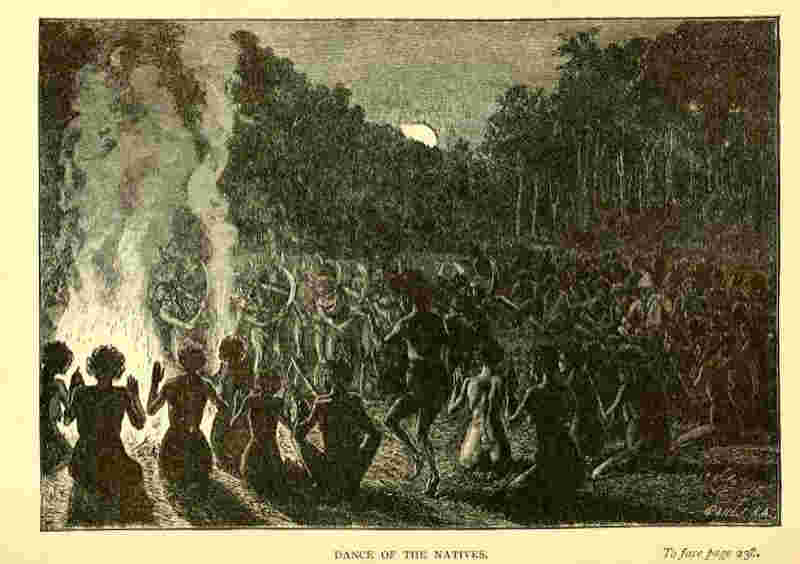

The dance always begins with the full moon and about half an hour before sunset. When the sun's last rays disappear from the horizon there is a pause until the moon rises, when the dancing begins in earnest and may last all night; but, not satisfied with the pale light of the moon, they kindle a large camp fire, the red flames of which, mingling with the white light of the moon, produce a strange fantastic effect. Toward morning they took a little rest, but before dawn I was again awakened by their monotonous song and clattering. When the sun rises it becomes too hot to dance.

The natives are wonderfully frugal in their eating at their festivals. I have never seen them eat together for pleasure or to celebrate any event. Anything like a banquet is entirely out of the question, nay, on the occasion I have described they might be said to be fasting. Those invited had taken no provisions with them, as they expected to be fed by their hosts. The latter supposed that the guests would bring food with them, and the result was that they had to subsist on almost nothing during the three days devoted to the dance. Some of them got a little tobacco. There were no other stimulants, for the blacks of Herbert river produce no intoxicating drink. They contented themselves with pleasure and water, but when the three days were gone they had to take to the scrubs and look for tobola. After gathering tobola for a few days, they renewed the dance in another place, where the same songs and the same performances were repeated, after which they again took to the woods to find means of subsistence.

In this manner the scene of the dance gradually approached Herbert Vale, and as the dancers were on a friendly footing with the blacks of that district, they gave entertainments on two evenings for their benefit. These festivities continued for nearly six weeks. On the other hand, it may take years before the blacks give another dance, for they must have new dances and new songs every time they dance, and their song-makers and dancing-masters, do not care to bother their brains with too much exertion.

While the blacks went up into the mountains to gather tobola, I persuaded Nilgora and one or two others to remain with Yokkai and me. I did not like to leave a place where boongary were to be found without securing a full-grown specimen, but they preferred to go up the mountains with the others, and were tired of hunting for me day after day. The natives are fond of change, and cannot endure monotony. They repeatedly tried to convince me that there were no more boongary, but I knew this to be mere pretext. I explained to them what I would pay them, and though I offered them all I had, even the shirt I wore, if they could procure me a boongary, they still answered Wainta boongary wainta? maja, maja ! nongashly yongul! (Where is boongary, where? no, no! there is but one in the woods).

Finally Nilgora and his men started early one morning "to go hunting with Balnglan." As he returned in the evening without any game, I had the next morning to renew my persuasions, and I showed him my tobacco. My provisions were no temptation to Nilgora, for I had none, and as I had already given him a shirt, the one I wore was no inducement to him. My last hope was my hat, an ornament highly prized by the blacks. He finally yielded, but to no purpose, as he returned in the evening as empty-handed as the day before.

Nilgora started for the mountains to attend the dance, while Yokkai and I betook ourselves back to Herbert Vale.

Nilgora was a typical savage, and as he had never before been in contact with white men, he was more easy to manage than the others, but was reticent and reserved. I was surprised to find him always armed with a sword-bayonet, the history of which it was impossible for me to get at. He was very much afraid of the white men, and for this reason he never came down from the mountains, and hence I infer that this weapon must long have travelled from tribe to tribe before it came into his possession. The native police do not use bayonets.

What particularly attracted my attention in Nilgora's looks were his tall powerful figure and his almost Roman nose, another proof to me that the natives here are mixed with the Papuans.

On the descent to Herbert Vale, Yokkai had the important task of carrying the skins in a bag. They had to be handled with great care, a fact that my black friend did not understand. Fortunately, he was afraid of the poison with which the skins were prepared, and this made him very circumspect.

In a cheerful frame of mind I proceeded down to the grassy plain. The dark claws of the boongary protruding out of the bag reminded me of what had been accomplished during the past few days, and besides it was a source of gratification to me that Yokkai did not, on a nearer acquaintance, disappoint the good hopes I had formed in regard to him on our first meeting. I felt that I could look the future cheerfully in the face, and I had reason to hope for good results so long as he was my companion. Yokkai was well acquainted with several of the most savage tribes in the neighbourhood, and with his help it would be more easy for me to secure companions on my expeditions. By reason of his naivete and good humour, I might count on having in him a lively and entertaining companion. Nor was he so savage and greedy as the other blacks. A circumstance which made him particularly devoted to me was his decided eagerness to become a "white man." His ambition was to eat the food of a white man, to smoke tobacco, to make damper, to shoot, to take care of horses, to wear clothes, and to talk English.

He told me a number of stories in regard to himself, and gave me much interesting information about the life and customs of the natives. Among other things, he said that he once had stolen from a white man, but it seems that in connection with that he acquired a great dread of the white men and their dangerous weapons. The whites were too angry, he said, and he assured me that he never more would gramma - that is, steal. Together with his comrades, he had ventured to go down to a farm near the coast, where he had been tempted by the sight of a wash-tub containing some clothes. On one of his shoulders he still bore the mark of a rifle ball, by which he had been greeted on his visit to the white man.

My plan now was to go to the tableland seventy miles to the west, where Mr. Scott, the owner of Herbert Vale, had his head station, the Valley of Lagoons. Up there it rains less in the rainy season than it does at Herbert Vale, and for this reason I decided to change my headquarters. When I came to the station, I met a white man who was going the same way as I, and we decided to travel together. Yokkai remained at Herbert Vale. The next day, January 30, we proceeded toward Sea-View Range, where we arrived the first afternoon. Here my companion wanted to encamp for the night.

I looked back upon the scrub-clad mountains on the other side of the valley. The air was clear, and the setting sun caused long shadows to fall in the mountain declivities. Far away, on the summit of a mountain, smoke was ascending. The blacks were burning the grass and were hunting the wallaby, free from every care and anxiety. The palms, the ferns, the rays of the sun glistening in the waterfalls, all this charming scenery I was now to abandon, and I was to live at a station with the white men on the prosy plains. No, this was not possible; I longed to get back to my black friends! When I saw the sun setting amid an effulgence of crimson, and thus indicating fine weather for the morrow, my mind was made up. I decided to wait for the rain as long as possible, and this year the rainy season set in unusually late.

I bade farewell to my travelling companion, and started back for Herbert Vale.

Early the next morning I went in search of Yokkai, whom I soon found. He and I started up the mountains to procure, if possible, more people to assist us.

In a small tribe which we came to, some of the natives were found willing to go with us, and soon afterwards we had the good fortune to meet Nilgora and "Balnglan." We made our camp in the same place as before - on the old dancing-ground. Nilgora was now very accommodating. He had employed his time since we parted in eating tobola, and was now longing for the white man's food, which he had learned to like when he was with me before. During the four days we spent here we succeeded in securing a small female boongary and a young one. Thus I now had in all five males and one female, though none of them were full grown. The female (represented on the coloured plate) had a little young one in her pouch, but the black had already given it to "Balnglan," thinking it was worthless.

One day, when Yokkai and I were left alone in the camp, he suddenly broke out, "Poor fellow, - white-fellow!" Thinking that he referred to me, I, half angry, asked him what was the matter. "Poor fellow, white-fellow - Jimmy," said he, beating the back of his head, "Jimmy, white-fellow ngallogo" - that is, "in the water." I now understood that something was the matter, and on inquiry at last found out that the same Jimmy who had been with me before had killed a white man and thrown him into the water. The white man had been camping near a river in the middle of the day, "while the sun was big, "not far from Herbert Vale. Jimmy had gone to him and offered to find fuel and build a fire, services which were accepted. The white man made his tea and sat down to eat, but Jimmy did not get any of the food, and at once became angry, and struck the white man on the back of the head with his tomahawk as he brought his tin cup to his lips to drink, so that he fell down dead. Then Jimmy robbed all that the white man had and threw his body into the water.

The report of the murder made a deep impression on me. Perhaps I ought to be satisfied with the results I had already gained. If I remained longer I might meet with a similar fate. I did not dare show Yokkai that the information affected me, though the words did escape my lips, that the black police would be angry with Jimmy and kill him.

When Nilgora came home in the evening, I heard Yokkai at once informing him "that the police would kill Jimmy." That whole evening the blacks were very reticent and unapproachable. Doubtless my ill-advised statement had frightened them, for they were aware that the police paid no respect to persons, but would shoot the first native they found, and they were also afraid that Yokkai would have to suffer for his thoughtlessness in telling tales out of school.

It was necessary to be equal to every emergency, for it was in their power to hinder the news of the murder from spreading. To avoid every danger, I resolved to be on the alert that night - the only night I ever kept awake during my life with the blacks. As was my custom, I fired a shot to remind my companions that my weapon was still in existence.

The natives were lying down round the fire in front of the opening of my hut, and from time to time they cast sly glances at me lying with half- closed eyes in my hut. The camp fire made it easy for us to watch each other. To convince them that I was wide awake, I now and then ordered them to fetch wood for the fire. I did not feel at all safe, and not until morning did I fall asleep, exhausted with fatigue.

When I opened my eyes the first rays of the morning sun were shining into my hut, and it was a source of the keenest gratification to know that I was unscathed. Never before had the dewy tropical morning seemed so beautiful as it did after this night.

I decided to go back to Herbert Vale for the present, and the same day Yokkai and I started on our return. I was determined to do all in my power to secure the punishment of Jimmy. Something ought to be done to show the blacks that they could not with impunity take the life of a white man.

Jimmy had accompanied me on several expeditions, so that I knew him well. He was a brutal, despotic fellow, and very reserved. Not long before this he had also killed one of his wives. He had robbed a man of his pretty young wife, Molle-Molle. But she loved her first husband and could not get on well with Jimmy, the less so as he had another wife, who was very jealous and always inflamed him against Molle-Molle. She tried to escape to her former husband, but was recaptured by Jimmy, who cut her on the shoulder with his axe to "mark" her. Still, she soon again found an opportunity to escape, and came to Herbert Vale, where I then happened to be staying. On her shoulder was a large open wound, which did not, however, appear to give her much pain. She requested me to shoot Jimmy, for he was "not good." In spite of her beautiful, beseeching eyes and her coquettish smiles, I could make her no promise, but I urged her to make haste and go to her former husband, whom she was seeking. The same night she disappeared.

I afterwards learned that she had found the man she loved, but her joy was of short duration. Jimmy was the stronger of the two men; he recaptured her, and punishment was again inflicted. According to the statements of the natives, he had almost killed her. He had struck her with a stone on the head, so that she fell as if dead on the hot sand. There he left her, in the middle of the day, after covering her with stones. The next time I saw Molle-Molle she had grown very thin and pale, and had great scars on her head. She was on the point of going with Jimmy down the river to another "land." On this journey he killed her with his tomahawk, and an old man buried her. This happened only three weeks after Jimmy had slain the white man.

Yokkai was afraid that he would be killed by the blacks at Herbert Vale, because he had revealed the murder of the white man, but I quieted him with the assurance that his name should not be mentioned.