The rainy season - How the evenings are spent - Hardy children - Mangola-Maggi's revenge - The crania of the Australians - The expedition to Cardwell - Dalrymple Gap - A scandalous murder - Entry into Cardwell - Yokkai as cook - "Balnglan's" death - Tobacco cures sorrow.

It grew more and more difficult to secure serviceable men. Yokkai I could usually depend on, but all the others I suspected more or less. Several times I was nearly ready for an expedition, when it began to rain. The weather was, of course, very unreliable during the rainy season. Old Walters had gone down to Cardwell for provisions, and I was left alone at the station with the Kanaka, where time hung heavily on my hands, for I had but few books. I kept writing as long as I was able, and the rest of the day I sat in the kitchen chatting with the Kanaka and the blacks, who usually came in late in the afternoon to warm their naked bodies by the fire. Their bodies were washed clean by the rain, and the wet steamed off them in the warm kitchen. They had a hard time of it during this season. The weather was cold and wet, and the women did not find much food in the woods, so that they suffered from hunger.

We generally sat round the fire, and the blacks told stories from their everyday life. One of them, who was the most frequent visitor, was Jacky, whom I mentioned before, a cunning black man, but upon the whole a good-natured, sociable fellow, who was highly respected by his companions. We therefore looked upon him as a sort of chief. One evening he remained long, and entertained us with his stories. The conversation turned upon our flour which was nearly finished, and it was stated that we soon would have to live on the potatoes in the garden until the overseer returned. It might take weeks before he came back, as the rivers had overflowed their banks and the rain still continued. Jacky, the rogue! pitied us. The next morning the Kanaka told me that most of the potatoes were gone. Either Jacky's women had stolen them, while he kept us talking to prevent any suspicion on our part, or he must have taken them immediately after he left us.

After a week's continuous rain we again got clear weather. The only pleasure I had had during this time was bathing. Whenever the weather permitted, I would go down to the river in the misty cold air, but it was necessary to keep a sharp look-out for crocodiles and not venture too far out in the stream. In the same stream where I was in the habit of bathing, a dog had recently been caught by a crocodile, while swimming by the side of his master. Thus the dog saved the man's life, for the crocodile is particularly fond of dog's flesh. Strange to say, the natives are not afraid of swimming across a river, but I would not advise a white man to attempt it.

Whenever it was possible I made excursions with the blacks, even during this time. One day while we were out I met a black woman, who I knew had a child two weeks old. She carried a basket on her back, and I, assuming that the child was in the basket, asked her to show it to me. She at once placed the basket on the ground, thrust her hand into it, seized the child by the feet, and held it with the head down for me to look at. The child awoke and began to cry a little, but did not seem to suffer much by this treatment. The children are, upon the whole, hardy. At a station near the tropics the white people several times saw a child only a few days old lying out in the cold on a piece of bark with hoar-frost round about it; and apparently it was not injured thereby.

At another time the conversation turned on a child that had died about a month ago. One of the natives, who was aware that I collected various things, asked me whether I would like to get this child, and added: "Why have they been so stupid as to lay it in the ground? You and I will dig it up and hang it in a tree to dry. "He was very eager to undertake this work for me, hoping thereby to earn some tobacco. The child's mother, who had not thought of the possibility of getting any profit out of her dead child, became from this moment very eager to sell it.

It is not often that it is so easy to get the natives to part with their dead. They dislike to disturb their own, and are afraid to meddle with those of other tribes. At this very time I was trying to secure a cranium of a full-grown individual, and in connection with this I had some very interesting experiences. I offered a reward of tobacco for the head of a man of a distant tribe, who some time ago had been killed at a borboby. From fear of the strange tribe they could not be persuaded to procure it, so I made up my mind to try to get it myself I took Yokkai with me to show me the grave, but I did not find it.

Finally I succeeded in inducing Mangola-Maggi to fetch the head; but the skull he brought me belonged to a young person and not to a full-grown man. Besides, there was a large hole in the top of it, which made it much less desirable as a cranium. I asked him what had produced the hole. "Dingo has eaten it," he said. Though I insisted that this could not be true, he kept asserting that it was the right head. As, however, he got no tobacco and as I promised him a large amount if he would bring the right one, he set out again in company with another native. After he had gone, the blacks explained to me the facts concerning this skull. Mangola-Maggi as a young man had experienced great difficulty in getting a wife, and had therefore requested an old man to give him one of his. But, as was natural, the old man refused to do this. Mangola-Maggi, who was a person of high authority on account of his ability to secure human flesh, became angry, and decided to take revenge. On meeting the young son of the man, he struck him on the head with a stone and killed him, and it was the skull of this young man that they had now brought to me and were trying to get a reward for. The body he had eaten immediately after the murder.

The next day Mangola-Maggi and his companion brought the right cranium and got their reward. When I reproached Mangola-Maggi for his conduct toward the old man's son, he simply shrugged his shoulders and smiled. I afterwards learned that he was challenged by the father to a duel with wooden swords and shields, and that in this manner the whole affair was settled.

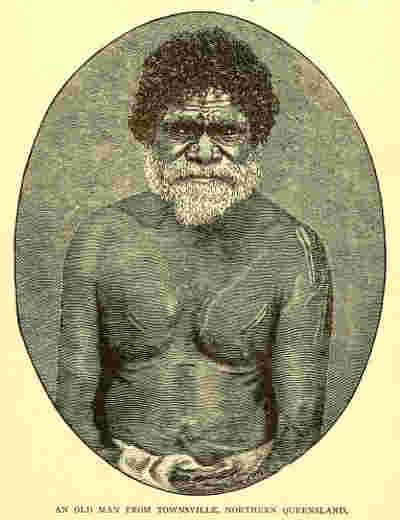

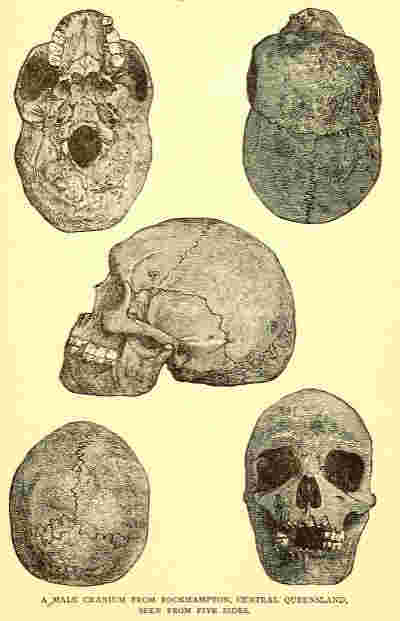

It is a well-known fact that the Australian natives, according to Gustaf Retzius, belong to the prognathous dolichocephalous class. Their projecting jaws make them resemble the apes more than any other race, and their foreheads are as a rule very low and receding. The bone is thick and strong. Few crania are to be found without marks of injuries, whether they be male or female. The muscles of the face, particularly the masticatory muscles, are very fully developed; the superciliary arches are very prominent; the cheek-bones are high, and the temporal fossae very deep. The skull-bones form a high arch. The orbital margin is very thick, the nasal bones are flat and broad, and the teeth large and strong, the inner molars having as many as six cusps. The hollow of the neck takes an upward and receding direction.

In the eight crania brought by me from Central and Northern Queensland the length-breadth index is 71, the length averages 180.5, and the breadth 128. The dolichocephalous character of the skull is mainly owing to the great narrowness of the cranium.

The facial angle averages 68°. Index orbitalis is microseme (81.5), index nasalis is platyrhine (53), and Daubenton's angle averages 5°.

The male crania have the savage type even to a greater degree than the female.

The above measurements, particularly the small capacity of the cranium, and the low receding forehead, which is unfavourable to a development of the frontal lobes, indicate the low plane of intellectual development of the Australian natives. The smaller the skull is the lower the race ranks in culture, but the organs of the face are all the more developed in comparison with the rest of the head.

The features distinguishing the cranium of the Australian from that of the European are, in the first place, the projecting jaws (the prognathous character), which are very rare and never marked among Europeans; in the second place, the low forehead and the small capacity, which among Europeans would be called microcephalous, and would indicate a weak mind; in the third place, the flat nose, which is also very rare in Europe; and finally, the large Daubenton angle.

In course of time we got better weather, so that I was able to start on a long expedition to Cardwell to buy provisions, and thereupon to examine the country north-west of this village. Yokkai and I succeeded after much trouble in gathering a few people for this journey. We also had the dog "Balnglan." All looked fresh and green after the rain; but it is wonderful how quickly everything dries up again, and how soon the rivers fall to their usual level. After all the rainfall the air was cool and very pleasant.

One evening I got a tangible proof, showing how important it is to clear with fire the ground on which one is going to camp for the night. Yokkai called my attention to the remains of a venomous serpent that had been in the grass. The above precaution is also important in sanitary respects, for the old grass is full of miasma, which makes the ground unhealthy.

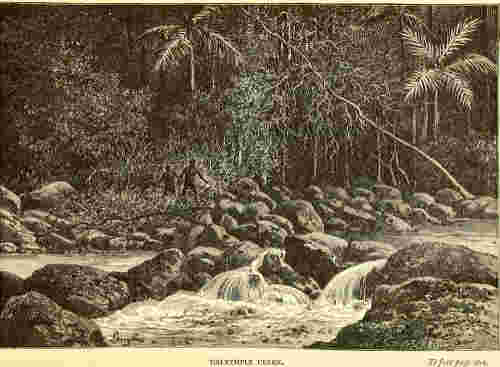

On our way we passed the place on Dalrymple Creek where Jimmy had murdered the white man. A heap of stones marked the spot where the postman had buried him. In the pool of water hard by I found a few bones. Soon after this we crossed the ridge at a place called Dalrymple Gap. To a person looking down from the summit there is a most beautiful view on either side. The spectator is greeted by a luxuriant tropical vegetation; palms and bananas, and a multitude of other trees of greater or lesser size, cover the ground, while across the gap hangs the telegraph wire which connects civilised Australia with Europe. It made a strange impression on me to find this emblem of civilisation after spending so long a time among the savages. A wide swath for the telegraph wire is cut through the dense forest, and continues its way northward all the way to Cape York. This opening must constantly be cleared, otherwise the rank vegetation would soon disturb the telegraph.

In these very regions a horrible murder was committed a few years ago by the blacks. The fact is well known in Northern Queensland, but except the natives, very few people are familiar with the details of the murder. The natives often talked with me concerning this event, which has not been forgotten by the white population either. The blacks did not hesitate to talk about it now, as so long a time has elapsed since it happened.

A settler named Mr. O'Connor, who had come to reside on the Lower Herbert, cultivated a farm, and employed a great many blacks to help him to clear the scrubs and to work in the fields. He paid them well, was very kind to them, and did not shoot them, as so many of the other colonists did, but was what is called "a blacks' protector." He paid them in meat, flour, and tobacco, but was too kind to them, and so the natives felt perfectly safe and had an irresistible desire to possess all his property.

They resolved to make an attack on his farm, and marched against the house armed with wooden swords and shields. O'Connor became alarmed, took his revolver, and finally had to shoot at them. But at every shot the natives ran behind the trees and shouted: " Shoot away, it will soon be our turn!" At last he had fired his six shots without hitting one of them. They had ceased to fear him to such a degree that they did not even respect his revolver, and rushing upon him, they slew him with their heavy swords, mangled his body, and plundered his house. They took the bananas in his garden and stole his chickens. His wife was dragged in an unconscious condition into the woods, where she was killed.

A police officer happened at the time to be on a tour of inspection in the neighbourhood. As O'Connor was the only settler in this district, the inspector wanted to visit him, and thus he discovered the crime that had been committed. He ordered a battle of the blacks in all directions. The troopers, who had on several occasions enjoyed the hospitality of the settler, were furiously enraged, and pursued the criminals like bloodhounds. The blacks report, however, that they did not succeed in shooting more than two of the men - an old man and a youth - but nearly all the women fell into their hands. The women, who generally are spared by the native police, were on this occasion obliged to suffer for the crimes of the men, and even the children were murdered and thrown into the flames.

This account, given me by several natives whose statements agreed, I consider perfectly reliable.

We encamped near Cardwell, a little settlement of about a hundred inhabitants on the seashore. I had great trouble in getting any of my men to go with me into the village, but finally succeeded in persuading one man to accompany me, while the others remained in the camp awaiting our return.

Our entrance into the village attracted considerable attention. I was on horseback, and my attendant, Morbora, marched at my side in his "garments of paradise." With one hand he shouldered my gun, and with the other hand he led the packhorse. We must have looked like travelling gypsies.

The people of the village gathered round us, and asked with the greatest curiosity how I could live among the natives without being killed. They all knew me from the postman, whose route began at Cardwell. I at once went to the "hotel" - for there is no town with twenty inhabitants without its hotel - to get my dinner, and procured for Morbora, who was sitting on the verandah and taking care of the horse, a large amount of leavings - "a black-fellow's meal," as it is called. He seemed to enjoy the food immensely, as he had never before had such a feast. He was in perfect ecstasy over all that he saw, and every trace of fear had left him. The white men entered into conversation with him, and it surprised me to see how well he used the few English words I had taught him. He felt like a lord as he sat there eating the food of the white man.

I paid a visit to the police magistrate, and talked with him about Jimmy. Then I bought provisions and returned to the camp, bringing with me woollen blankets for all my men. The Government of Queensland annually distributes blankets to the natives on the Queen's birthday, if they will but come and get them. This is the only thing the Government does for the black inhabitants. The day for distribution had not yet arrived, but I succeeded in getting blankets for my men in advance. Here, on the borders of civilisation, there are but few natives who avail themselves of this privilege, as they are too timid to approach the whites.

On our return to the camp these blankets were a source of joy and admiration. My blacks now made their first acquaintance with this sort of luxury, and they seemed to be perfectly delighted The flour and sugar I had brought made, however, the deepest impression on them. The amount was not large, but my blacks had never before seen such a lot of dainties. In their simplicity they thought all was to be eaten at once, though I tried to make them understand that it was to last a long time. I did not give them much of the sugar, as they were able to procure honey for themselves. Sugar had become an absolute necessity to me, and I was unable to swallow my food without sweetening the water. It frequently happened that I lay down in the evening munching dry food without being able to swallow it. This made the natives envious, for, having devoured their own share at once, they wanted to get what I was trying to eat.

We proceeded up the Coast Mountains north-west from Cardwell, and encamped near the summit on a grassy lawn in the scrub, constructing our huts with more care than usual, and digging ditches round them so that we could keep dry. The vegetation here was remarkably luxuriant. We had a fine view of the ocean and of the coast below us, including a long series of scrub-clad hills toward the north.

Yokkai, whom I had educated as well as I could to prepare the food, was very proud of being permitted to handle the white man's things. I had taught him to wash himself and to keep himself clean, but only insisted on his doing this when he acted as cook, and at such times I was always present, as he was especially fond of baking damper. It was never necessary to ask him twice to do this. He made no delay in procuring the bark, on which he carefully laid the necessary amount of flour, adding the proper amount of water, and kneaded the dough with a skill that a baker might envy. When the dough was kneaded, and he had shaped it, he threw it a few times into the air, and caught it like a ball, to show us that he understood the art perfectly. After placing the cake in the ashes, he carefully collected all the small pieces of dough remaining and made a little cake of them, which he baked for his own special benefit. Besides, I gave him, as his perquisite, a small piece of the damper when it was done.

As he gradually grew more accustomed to the baking, I noticed that the remnants of dough on the bark kept increasing in quantity, but as he was, upon the whole, a rather scrupulous man, I said nothing about it. I also gave him permission to prepare the meat. I had abandoned the tin pail and now prepared my meat in the same manner as the natives.

We made daily excursions into the woods, which were unusually dense and abounded with lawyer-palms. As usual, the leeches were very numerous in 'these mountains, and were very annoying. As you walk through the woods, exhausted and dripping with perspiration, you scarcely notice their bites before they have satisfied their thirst for blood, but then the blood flows freely from the wound. The ticks, however, are a far greater annoyance. All the scrubs up here are so full of these insects that a white man dreads to enter them, though the natives are not at all annoyed by them. A splendid remedy for the itching caused by these insects is lemon juice, and hence I always took lemons with me on my expeditions from Herbert Vale. I put this juice over my whole body, and thus the insects were doubtless killed, for I immediately felt relief. A larger species of tick is also found here which kills the dogs of Europeans, but, strange to say, has no effect on the dingo. They are, however, a great inconvenience to the white man, and should at once be killed by applying petroleum to them. It is useless to try to jerk them out, for a part of them will remain in the flesh and may cause bad sores. I know a man who became blind for a few minutes on account of a tick which he could not get entirely rid of, a part of it remaining in the flesh of his back.

On my wanderings here, my blacks found in a pool formed by a mountain brook a toollah (Pseudochirus archeri). The natives all shouted at once, yarri. They told me that the large yarri, which I never succeeded in securing, but of whose existence I have no doubt, subsists for a great part on this animal, which, in this instance, it had left in the cool water for future consumption. One is tempted to believe that the yarri understands the preserving quality of the water. The natives, too, preserve their meat in the water during the hot summer months, as the temperature of the water is, of course, lower than that of the air. The fact probably is, that the yarri has found the water to be a safer place for storing the meat. The toollah was put between some stones near the edge of the river. I was much pleased with what the natives told me, for it awakened in me hopes of securing a specimen of this large marsupial. Fortunately, I had strychnine with me. I poisoned the toollah and laid it on the bank. Farther up the stream I left several pieces of meat, likewise prepared with poison, a source of great aggravation to the blacks, who would have liked to eat the meat. As we went to examine the snares every day, I was very much afraid that our dog might eat the poison, and I kept constantly warning the blacks.

One day, as we were returning to the camp, the natives were to take a beat by themselves through the scrub. I urged them particularly not to return along the river, but to come through the woods, so as to avoid the poisoned meat. Later in the day, as they were coming home, I heard them talking about poison and about "Balnglan." I at once became suspicious, and asked if the dog had eaten any of the poison. They denied it, but when I pressed them with questions they admitted that they had returned by the way of the river, probably because they were too lazy to go the other way, and they also confessed that "Balnglan" had taken the poisoned toollah in his mouth. Yokkai had at once taken the toollah out of "Balnglan's" mouth, so that he had not eaten any of it. No sooner had they made this statement than the dog fell into spasms. I rushed into my hut, mixed as quickly as I could some tobacco and water to pour down the dog's throat, while Yokkai and another man held it, but it died at once.

Yokkai gazed at it for a moment, then turned away and wept bitterly. He sat down and wrung his hands in despair, while large tears rolled down his cheeks. The other man also began to sob and cry aloud.

Though I felt the deepest sympathy for them, I could not endure these endless lamentations. I got two large pieces of tobacco, and offered it as a reward to them if they would cease their sobbing. Yokkai became silent at once and straightened himself up, while he looked at the tobacco with his eyes full of tears. He accepted it with contentment, but there was not a smile on his face. The other continued sobbing until it came to be his turn to get tobacco, then his sorrow was cured instantly.

I myself was touched by this event, for the good beast, which lay there dead and rigid, had been of great service to me. It was the best dog for miles round, and was the most intelligent dingo I have ever seen. I not only placed a high value on it, but I was also very fond of it, though it had several times attacked my leather traps, such as strings, shoes, and even my revolver case. I was anxious to preserve at least its fine black skin with white breast and yellow legs, and I suggested to Yokkai that he should let me have it. Knowing that such a request would be opposed, I at the same time offered tobacco as a compensation. He at first objected, but when he saw two whole sticks of tobacco, every scruple vanished and his eyes beamed with satisfaction. He even assisted me in skinning the dingo, and from this time he regained his usual good humour. He had some suspicions that Nilgora, the owner of the dog, would become angry when he learned of this sad event, but he felt certain that he could satisfy him by giving him his woollen blanket and some tobacco.