Native politeness - How a native uses a newspaper - "Fat" living - Painful joy - boongary, boongary - Veracity of the natives - A short joy - A perfect cure - An offer of marriage - Refusal.

The blacks had for several days been talking about a dance to be held in a remote valley.

A tribe had learned a new song and new dances, and was going to make an exhibition of what it had learned to a number of people. The Herbert Vale tribe had received a special invitation to be present, and the natives assured me that there would be great fun. My action was determined by the fact that Nilgora, who owned the splendid dog "Balnglan," already mentioned, would be there. But I had my misgivings on account of the horses, for as we were in the midst of the rainy season, I ran some risk of not being able to bring them back again.

Early one morning we set out, a large party of men, women, and children. A short time before reaching our destination we were met by a number of natives, for they expected us that night. Some of the strangers were old acquaintances of my people, but this fact was not noticeable, for they exchanged no greetings. In fact an Australian native does not know what it is to extend a greeting. When two acquaintances meet, they act like total strangers, and do not even say "good-day" to each other. Nor do they shake hands. After they have been together for some time they show the first signs of joy over their meeting.

If a black man desires to show how glad he is to meet his old friend, he sits down, takes his friend's head into his lap, and begins to look for the countless little animals that annoy the natives, and which they are fond of eating. When the one has had his head cleaned in this manner, the two change places, and the other is treated with the same politeness. I accustomed myself to many of the habits of the natives during my sojourn among these children of nature, but this revolting operation, I confess, was a great annoyance to me. A more emphatic sign of joy at meeting again is given by uttering shrieks of lamentation on account of the arrival of strangers to the camp. I was frequently surprised at hearing shrieks of this sort in the evenings, and found upon examination that they were uttered in honour of some stranger who had arrived in the course of the day. This peculiar salutation did not last more than a few moments, but was repeated several evenings in succession during the visit of the stranger. The highest token of joy on such occasions is shown by cutting their bodies in some way or other.

Later in the afternoon we arrived in the valley where the dance was to be. Those who were to take part in the dance had already been encamped there for several days. We had also taken time by the forelock, for the festivities were not to begin before the next evening. Several new arrivals were expected in the course of the next day, among them Nilgora. A proposition was made that two men should be sent to meet him on the mountain and request him to look for boongary on the way down, and early the next morning before sunrise they actually started after being supplied with a little tobacco.

My men and I had encamped about 200 paces from the others. I made a larger and more substantial hut than was my usual custom. It did not reach higher than my chest, but the roof was made very thick and tight on account of the rain. At first the blacks were very timid, but gradually the bravest ones among them began to approach my hut. As was their wont, they examined everything with the greatest curiosity. Yokkai walked about in the most conscious manner possible, and assumed an air of knowing everything. He brought water from the brook, put the tin pail over the fire, and accompanied by one or two admirers, went down to the brook to wash the salt out of some salt beef which was to be boiled. The matches, the great amount of tobacco, my pocket handkerchief, my clothes, and my boots, - all made the deepest impression upon the savages. After unpacking, a newspaper was left on the ground. One of the natives sat down and put it over his shoulders like a shawl, examining himself to see how he looked in it; but when he noticed the flimsy nature of the material, he carelessly let it slip down upon the ground again.

My white woollen blanket provoked their greatest admiration, which they expressed by smacking with their tongues, and exclaiming in ecstasy: Tamin, tamin! - that is: Fat, fat! The idea of "excellent" is expressed by the natives, as in certain European languages, by the word "fat."

It is an interesting fact that, much as the civilised Australian blacks like fat, they can never be persuaded to eat pork. "There is too much devil in it," they say.

At noon I heard continuous lamentations, but as I supposed they were for some one deceased, I paid but little attention to them at first. Lamentations for the dead, however, usually take place in the evening, and so I decided to go and find out what was going on. Outside of a hut I found an old woman in the most miserable plight. She had torn and scratched her body with a sharp stone, so that the blood was running and became blended with the tears, which were flowing down her cheeks as she sobbed aloud.

Uncertain as to the cause of all this lamentation, I entered the hut, and there I found a strong young woman, lying half on her back and half on her side, playing with a child. I approached her. She turned her handsome face toward me, and showed me a pair of roguish eyes and teeth as white as snow, a very pleasing but utterly incomprehensible contrast to the pitiful scene outside. I learned that the young woman inside was a daughter of the old woman, who had not seen her child for a long time, and now gave expression to her joy in this singular manner. I expressed my surprise that the old woman's face did not beam with joy, but this seemed to be strange language to them. These children of nature must howl when they desire to express deep feeling.

Night was approaching, the sun was already setting behind the horizon, the air was very hot and oppressive, and it was evident that there would soon be a thunderstorm. The blacks sat at home in their huts or sauntered lazily from place to place, waiting until it became cool enough for the dance to begin. I had just eaten my dinner, and was enjoying the shade in my hut, while my men were lying round about smoking their pipes, when there was suddenly heard a shout from the camp of the natives. My companions rose, turned their faces toward the mountain, and shouted, boongary, boongary! A few black men were seen coming out of the woods and down the green slope as fast as their legs could carry them. One of them had a large dark animal on his back.

Was it truly a boongary? I soon caught sight of the dog "Balnglan" running in advance and followed by Nilgora, a tall powerful man.

The dark animal was thrown on the ground at my feet, but none of the blacks spoke a word. They simply stood waiting for presents from me.

At last, then, I had a boongary, which I had been seeking so long. It is not necessary to describe my joy at having this animal, hitherto a stranger to science, at my feet. Of course I did not forget the natives who had brought me so great a prize. To Nilgora I gave a shirt, to the man who had carried the boongary, a handkerchief, and to all, food. Nor did I omit to distribute tobacco.

I at once began to skin the animal, but first I had to loosen the withies with which its legs had been tied for the men to carry it. The ends of these withies or bands rested against the man's forehead, while the animal hung down his back, so that, as is customary among the Australians, the whole weight rested on his head.

I at once saw that it was a tree-kangaroo (Dendrolagus). It was very large, but still I had expected to find a larger animal, for according to the statements of the natives, a full-grown specimen was larger than a wallaby - that is to say, about the size of a sheep. This one proved to be a young male.

The tree-kangaroo is without comparison a better proportioned animal than the common kangaroo. The fore-feet, which are nearly as perfectly developed as the hind-feet. have large crooked claws, while the hind-feet are somewhat like those of a kangaroo, though not so powerful. The sole of the foot is somewhat broader and more elastic, on account of a thick layer of fat under the skin. In soft ground its footprints are very similar to those of a child. The ears are small and erect, and the tail is as long as the body of the animal. The skin is tough, and the fur is very strong and beautiful. The colour of the male is a yellowish-brown, that of the female and of the young is grayish, but the head, the feet, and the under side of the tail are black. Thus it will be seen that this tree-kangaroo is more variegated in colour than those species which are found in New Guinea.

Upon the whole, the boongary is the most beautiful mammal I have seen in Australia. It is a marsupial, and goes out only in the night. During the day it sleeps in the trees, and feeds on the leaves. It is able to jump down from a great height and can run fast on the ground. So far as my observation goes, it seems to live exclusively in one very lofty kind of tree, which is very common on the Coast Mountains, but of which I do not know the name. During rainy weather the boongary prefers the young low trees, and always frequents the most rocky and inaccessible localities. It always stays near the summit of the mountains, and frequently far from water, and hence the natives assured me that it never went down to drink.

During the hot season it is much bothered with flies, and then, in accordance with statements made to me by the savages, it is discovered by the sound of the blow by which it kills the fly. In the night, they say, the boongary can be heard walking in the trees.

I had finished skinning the animal, and so I put a lot of arsenic on the skin and laid it away to dry in the roof of my hut, where I thought it would be safe, and placed the skin there in such a way that it was protected on all sides.

Meanwhile my men had gone down to witness the dance. Happy over my day's success I too decided to go thither and amuse myself, but before I had prepared the skin with arsenic and could get away, darkness had already set in, and the dancing was postponed until the moon was up. The natives had in the meantime retired to their camps until the dance was to begin again.

The tribe that was to give the dance had its camp farthest away, while the other tribes, who were simply spectators, had made their camps near mine. There was lively conversation among the huts. All were seated round the camp fires and had nothing to do, the women with their children in their laps, and those who had pipes smoking tobacco. I went from one group to the other and chatted with them; they liked to talk with me, for they invariably expected me to give them tobacco. Occasions like this are valuable for obtaining information from the natives. Still, it is difficult to get any trustworthy facts, for they are great liars, not to mention their tendency to exaggerate greatly when they attempt to describe anything. Besides, they have no patience to be examined, and they do not like to be asked the same thing twice. It takes time to learn to understand whether they are telling the truth or not, and how to coax information out of them. The best way is to mention the thing you want to know in the most indifferent manner possible. The best information is secured by paying attention to their own conversations. If you ask them questions, they simply try to guess what answers you would like, and then they give such responses as they think will please you. This is the reason why so many have been deceived by the savages, and this is the source of all the absurd stories about the Australian blacks.

Among the huts the camp fires were burning, and outside of the camp it was dark as pitch, so that the figures of the natives were drawn like silhouette pictures in fantastic groups against the dark background.

It amused me to make these visits, but my thoughts were chiefly occupied with the great event of the day. In the camp there were several dingoes, and although the boongary skin was carefully put away, I did not feel perfectly safe in regard to it. I therefore returned at once to look after my treasure; I stepped quickly into my hut, and thrust my hand in among the leaves to see whether the skin was safe; but imagine my dismay when I found that it was gone.

I was perfectly shocked. Who could have taken the skin? I at once called the blacks, among whom the news spread like wild-fire, and after looking for a short time one of them came running with a torn skin, which he had found outside the camp. The whole head, a part of the tail and legs, were eaten. It was my poor boongary skin that one of the dingoes had stolen and abused in this manner. I had no better place to put it, so I laid it back again in the same part of the roof, and then, sad and dejected in spirits, I sauntered down to the natives again.

Here every one tried to convince me that it was not his dog that was the culprit. All the dogs were produced, and each owner kept striking his dog's belly to show that it was empty, in his eagerness to prove its innocence. Finally a half-grown cur was produced. The owner laid it on its back, seized it by the belly once or twice, and exclaimed, Ammery, amme ry! - that is, Hungry, hungry! But his abuse of the dog soon acted as an emetic, and presently a mass of skin-rag was strewed on the ground in front of it.

My first impulse was to gather them up, but they were chewed so fine that they were useless. As the skin had been thoroughly prepared with arsenic, it was of importance to me to save the life of the dog, otherwise I would never again be able to borrow another.

Besides, I had a rare opportunity of increasing the respect of the natives for me. I told them that the dog had eaten kola - that is, wrath - as they called poison, and as my men had gradually learned to look at it with great awe, it would elevate me in their eyes if I could save the life of the dog. I made haste to mix tobacco and water. This I poured into the dog, and thus caused it to vomit up the remainder of the poisoned skin. The life of the dog was saved, and all joined in the loudest praises of what I had done. They promised me the loan of "Balnglan" again, and thus I had hopes of securing another boongary; of course they added as a condition that I must give them a lot of tobacco.

The next morning early I persuaded them to get ready for the chase, but they did not want me to go with them, as the dog was afraid of the white man.

Most of the blacks remained to witness the dance, for the camp was in a festive mood, and in the morning before daylight I was awakened by the noise. As soon as the weather became hot, they again gathered in groups under the shady trees, where they chatted in idleness until it became cool enough to dance again in the evening. I went from one group to the other. They asked me to give them European names, a request often made to me on my journeys among the tribes. The reason appeared to be that the savage blacks, who had not been in contact with the white man, were anxious to acquire this first mark of civilisation, which they found among my men, and which they imagined brought tobacco and other gifts. Among themselves these savage natives kept their own names, which, as a rule, are taken for both men and women from animals, birds, etc. The father will under no circumstances give his son his own name.

I gave them various Norwegian names. It was difficult for them to pronounce some of them, but such names as Ragna, Inga, Harald, Ola, Eivind, etc., became very popular.

One of the natives came to me and asked for some salt beef, giving as an excuse that he had a pain in his stomach, because he had for a long time eaten nothing but tobola, the main food of the natives during about two months of the year. This fruit, which grows in the scrubs on the mountain tops, is of a bluish colour, and of the size of a plum. The tree is very large and has long spreading branches, so that the natives prefer waiting until the fruit falls on the ground to climbing the trees for it. It is gathered by the women and brought to the camp, where it is roasted over the fire until the flesh is entirely burnt off and the kernel is thoroughly done. The shell round the kernel then becomes so brittle that it is easily peeled off. Then the kernels are beaten between two flat stones until they form a mass like paste. When they have been beaten thoroughly in this manner, they are placed in baskets and set in the brook to be washed out, and the day after they are fit to be eaten. The paste, which is white as chalk and contains much water, looks inviting, but is well-nigh tasteless. The blacks eat this porridge with their hands, which they half close into the form of a spoon. This food is certainly very unwholesome, for the natives, who, by the way, are very fond of it, often complained that they did not feel well after eating it for some time. The amount of nourishment in tobola is very small, and the natives eat a very large amount before they satisfy their hunger, a fact which, in connection with its indigestible character, cannot fail to produce harm. I have often wondered how they can preserve their health so well as they do, considering all the unwholesome and indigestible vegetable food they consume, and the great lack of variety. It is even more surprising that they have found out that there is any nourishment at all in the poisonous plants, which they know how to prepare, and which at the very outset would appear to be unfit for human food. It is also an interesting fact that different poisonous plants, or plants not fit to be eaten raw, are used in different parts of Australia and prepared by one tribe in a manner of which another tribe has no knowledge.

On my visits to the huts I met Chinaman, who had deserted me in so disgraceful a manner and ruined my whole expedition. He now imagined that all was forgotten. After a month the blacks think no insult is remembered, not even a murder. Chinaman tried to be polite, but I kept him at a respectable distance in order to show the blacks that I did not tolerate such conduct as that of which he was guilty.

Late in the afternoon we were overtaken as usual by a heavy thunderstorm. One flash of lightning followed the other in rapid succession. The thunder-claps were echoed back from the steep mountain walls, and I expected the trees around us would be struck by lightning every moment. The natives, however, were not afraid. At every flash of lightning they shouted with all their might and laughed heartily. It was a great amusement to them.

At sunset, just as the dance was to begin, Nilgora and his companions returned from their hunt, and to my great satisfaction they brought with them another boongary. This was also a male, but somewhat smaller than the one I had lost. On its back it had distinct marks of "Balnglan's" teeth. As I have since learned, this animal is hunted in the following manner:

The chase begins early in the morning, while the scent of the boongary's footprints is still fresh on the ground. The dog takes his time, stops now and then, and examines the ground carefully with his nose. Its master keeps continually urging it on, and addresses it in the following manner: Tshe' - tshe' - gangary pul - pulka - tshe' pul - tshinscherri dundun - mormango - tshe', pul - pulka! etc. - that is, Tshe' - tshe' - tshe' smell boongary - smell him - tshe' smell - seize him by the legs - smart fellow - tshe' smell - smell him, etc. If the dog finds the scent, it will pursue it to the tree which the animal has climbed. Then some of the natives climb the surrounding trees to keep it from escaping, while another person, armed with a stick, ascends the tree where the animal is. He either seizes the animal by the tail and crushes its head with the stick, or he compels it to jump down, where the dingo stands ready to kill it.

In the evening, when I came down to the blacks, who were waiting for the moon to give light to the dancers, my men expressed a fear that strange tribes would attack the camp in the course of the night. I ridiculed this fear, now that they were assembled in such numbers, but they replied that the strangers also were numerous, and they would not be at rest until I had fired a shot.

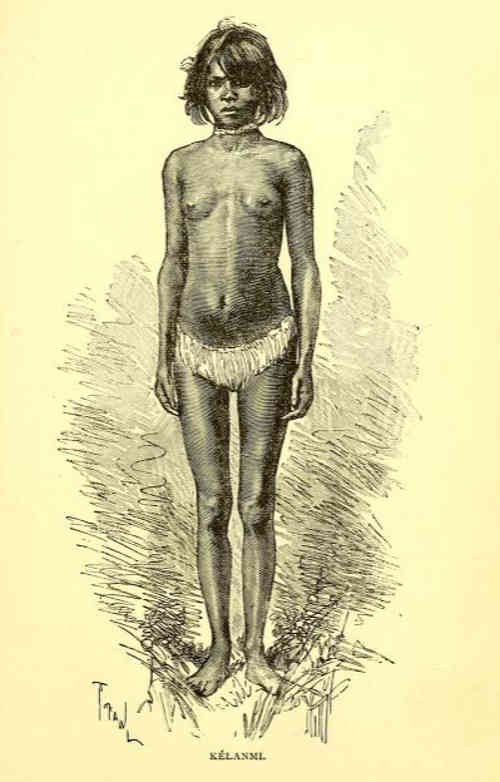

Thereupon a few persons came in great haste to the blacks with whom I was talking, from the camp of the dancers, who had evidently been frightened by the shot, and explained that they would like to talk with me, and asked me to go with them, so we all went to the dancers, where all was excitement; everybody was talking at the same time, but when I came nearer I could catch in the midst of the confusion such words as kola (anger), nili (young girl), Kelanmi Mamigo (Kelanmi shall belong to Mami). One of my men explained to me: The blacks wish to give you a nili. They are afraid of the baby of the gun.1

1 Go is a suffix, which means "with reference to"; thus literally, Kelanmi with reference to Mami - that is, me.

"Very well," I answered, "bring her to my hut."

The blacks had become afraid of me, having interpreted the shot I fired as a sign that I was angry, and to propitiate me they wished to give me Kelanmi, a young girl, who was looked upon as the prettiest woman in the whole tribe.

When I agreed to accept her they became quiet and their fears were allayed.

Evidently Kelanmi was afraid of the white man, and was reluctant to leave her tribe; when I went away I heard them scold her and try to force her to go to the white man. I learned that she was, in fact, promised to one of the blacks, by name Kal-Dubbaroh, and so I asked him to go with her to my hut. I kindled a fire in my hut, and waited for them to come with Kelanmi. The moon was just rising, so that I was able to discern the dark figures approaching me, but at first I saw no nili, as she was walking behind one of the men, who held her by the wrist. She made no resistance, and came willingly. When the party reached my hut the men let go of the girl, but said nothing, and I asked her to sit down. She was a young and tolerably handsome girl about twelve years old, with a good figure, and was clad in her finest attire in honour of the dance, both her face and her whole body being pretty well covered with red ochre. She was very much opposed to getting married, particularly to a white man, and sat trembling by the fire, awaiting the orders of her new master. To quiet her, I at once got some bread and beef, but she concealed it, out of fear of the bystanders, for such delicacies are too good for a woman. Then I gave her a little tobacco, which she also put away. No doubt she intended to give it to her old adorer Kal-Dubbaroh, who I suppose expected some compensation for his loss. I pitied the little embarrassed girl, and told her, to the great surprise of the spectators, that she might go, whereupon she immediately ran out. This puzzled the blacks, who could not conceive any other reason for my refusal than that I was displeased with her, and so they offered me another girl. But I tried to explain to them that all was well between us, and I proposed that we should go down and dance.

They were just beginning to dance when we came down to the camp, where I sat down among the spectators and amused myself by witnessing the manner in which the natives enjoyed themselves on such occasions. To give them a proof of my goodwill, I took a whole stick of tobacco and threw it down among the dancers. This liberality was a surprise to the natives, who, of course, vied with each other in trying to secure the tobacco. Quick as lightning, one of the men caught hold of the stick and ran with it to his hut.

On the way home Yokkai urged me to shoot Kal-Dubbaroh, saying: "Kal-Dubbaroh not good man." I could not quite comprehend the meaning of this. The fact was, however, as I afterwards learned, owing to his so frequently troubling me with this request, that Yokkai himself was anxious to marry Kelanmi, and consequently would like to have his rival out of the way.

The next day Nilgora again consented to go out hunting, and returned with a young boongary, still smaller than the others. The day was so hot that when I undertook to prepare the new specimen, the feet had already begun to decay, and I was afraid the animal would spoil before I got the skin off it. I therefore took it to the coolest place I could find, and prepared the skin. I sat in the shade of a gum-tree, and had to keep continually moving out of the sun's scorching rays. The flesh, which we roasted on the coals, had a fine gamey flavour, and did not taste at all like kangaroo meat. One circumstance, however, detracted from the enjoyment. The boongary, like most of the Australian mammals living in the trees, is infested by a slender, round, hard worm, which lies between the muscles and the skin. There these little worms, rolled together in coils, are found in great numbers. They did not trouble the natives, who did not even take the pains to pick them out.

They grumbled, on the other hand, because they were not permitted to gnaw the bones, especially the feet, which they looked upon as the best part of the animal.