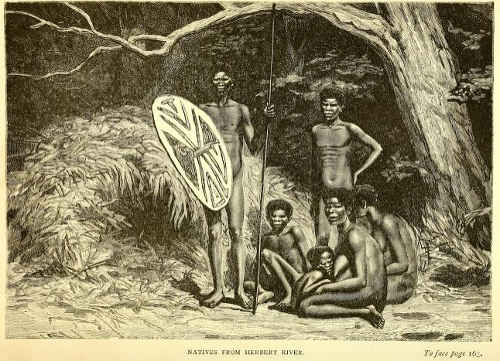

The position of woman among the blacks - The husband the hunter, and the woman the provider of the family - Black female slaves - "Marking" the wives - A twelve-year-old wife - Considerate husbands - Wives an inheritance - Deserted by my followers - Reasoning power of the blacks - Darkness and rain.

The wives of Willy and Chinaman had kept far in the rear of the expedition all the time, as they, in company with other women of the tribe, were in search of fruits and larvae. Among the blacks it is the women who daily provide food, and they frequently make long excursions to collect things to eat. The position of woman here, as elsewhere among savages, is a very subordinate one.

She must do all the hard work, go out with her basket and her stick to gather fruits, dig roots, or chop larvae out of the tree-stems. She finds the fruits partly within her reach, partly in the trees, which she climbs, though less skilfully than the men. The stick in question, the woman's only implement, is indispensable to her on her expeditions after food. It is made of hard tough wood four or five feet long, and has a sharp point at one end made by alternately burning it in the fire and rubbing it with a stone. Even at dances and festivals the married women carry this stick as an emblem of dignity, as the provider of the family.

The woman is often obliged to carry her little child on her shoulders during the whole day, only setting it down when she has to dig in the ground or climb trees.

When she comes home again, she usually has to make great preparations for beating, roasting, and soaking the fruits, which are very often poisonous. It is also the woman's duty to make a hut and gather the materials for the purpose. Her husband assists her in cutting down the four or five slender trees for the frame, but the woman herself has to carry the large armfuls of palm leaves or grass to the camp, and level the ground for the hut, removing with her stick and her fingers all inequalities. She also provides water and fuel.

When they travel from place to place the woman has to carry all the baggage. The husband is therefore always seen in advance with no burden save a few light weapons, such as spears, clubs, or boomerangs, while his wives follow laden like pack-horses with even as many as five baskets containing provisions. There is frequently a little child in one of the baskets, and a larger child may also be carried on the shoulders.

The husband's contribution to the household is chiefly honey, but occasionally he provides eggs, game, lizards, and the like. He very often, however, keeps the animal food for himself, while the woman has to depend principally upon vegetables for herself and her child. The husband hunts more for sport than to supply the family with necessaries, a matter that does not really concern him. Upon the whole he feels no responsibility as the father of a family, but lives a thoroughly selfish life, waiting in the morning until the grass is dry before he goes out, and often returning to the camp with empty hands, having consumed his game where he caught it.

He treats his wife with but little consideration, and is often very cruel; he may take her life if he desires. In cold rainy nights she is obliged to go out to fetch water and fuel. If in the evening I requested one of my blacks to do this, he usually transferred the order to one of his wives, who went at once; as a rule he had no regard for her age. During one night which I passed on a farm not far from Mackay, I heard a terrible cry in a camp of civilised blacks near by. On going down there the next morning we found one of the young women in a pitiful condition, bathed in blood and weeping; two of her fingers were broken. She said that her husband had flogged her during the night. I asked him why he had done so, and he answered that it had been very cold in the night, and that this wretch of a woman had not been willing to go at once and fetch fuel for the camp fire. He was an unusually capable black, who, on one occasion, had accompanied a Catholic missionary across the continent to the Gulf of Carpentaria. But with all his good qualities he had not yet learned to treat his wife otherwise than his black brethren, who do not regard her as a human being like themselves.

The worst crime a woman can commit is, of course, to run away from her husband, whose slave she in reality is. She is oppressed, but is as a rule contented with slavery, having no knowledge of a freer condition. She has no will of her own, and she knows that her husband will not brook opposition. But, however subject to the will of her husband she may appear to be, and however oppressed she has been for generations, many instances are still to be found where she has refused to submit to her fate and has taken flight. She may also have some one whom she adores, and a woman frequently runs away to a person she loves, although she risks punishment; she may even be maimed by her husband if he ever gets hold of her again. In such cases he usually gives her one or two blows on the back with his tomahawk, which the blacks call "marking" the woman. Frequently the woman is killed, particularly if she tries to run away a second time.

When a wife is punished for other errors, the husband usually gives her a rap on the head with the first object he can lay his hands on. As a result of this treatment the women are often marked or scarred from blows received from their cruel husbands. The punishments are quite informal, and are inflicted in the excitement of the moment, no matter whether others are present or not.

As the women perform all the labour, they are the most important part of the property of an Australian native, who is rich in proportion to the number of wives he possesses.

They usually have two, frequently three, sometimes four wives, and I saw one man who had six. All the wives live in the same hut with their husband. He who has many is envied by the others. "No one should have more than two wives," said my men to me, who had only one wife apiece, and whose highest ambition it was to double the number. The black man usually has a favourite wife, whom he prefers to the others and treats better. Still, polygamy does not give rise to as many family troubles as one would think, though there may be discord enough among the men on account of the women. As a rule, man and wife apparently get on very well, and the women are not constantly being flogged. I have even seen instances where the husband was governed by his wife, and was scolded and corrected by her, and I have also seen husbands ask their wives for advice; but such cases as these are, of course, very rare.

It must be admitted that sometimes the Australian treats his wives well, even in cases where the husband is the boss, and two of the men who were with me on this expedition were exceptions of this kind.

It was an unusually fine trait in the characters of Willy and Chinaman that they saved part of the provisions which they received from me for their wives. One afternoon, when they wanted to go and see their wives, they asked me to lend them a bag, and soon afterwards I saw them starting off with a large amount of provisions which they had saved. This consideration did not imply any self-denial on their part, for I had given them more than they could eat, but I have since learned that they sometimes did make sacrifices for their wives, and in this instance it may be said to their credit that they gave them what they themselves might have consumed at a later time.

Willy and Chinaman's wives were very young, one of them being a little girl of about twelve years. As long as the wives are so young I think they receive better treatment than they do later on.

Thus even Australian women may have their honeymoon. These two men were proud of their young wives, because it is, as a rule, difficult for young men to marry before they are thirty years old. The old men have the youngest and best looking wives, while a young man must consider himself fortunate if he can get an old woman.

A woman is delivered over to her husband when she is about nine or ten years old. It is simply ridiculous to see a man with a wife whom one would take to be his young daughter. She lives with her husband, who may be said to rear her, the two being at the same time really married. In this respect the custom existing among the more southern tribes, as, for instance, near Rockhampton, where the woman is not married before she has reached maturity, differs from that on Herbert river; even here, however, some respect is paid to her age, for a twelve-year-old wife is not expected to provide as much as a grown woman. "She runs about too much when she is so little," said Willy and Chinaman, meaning that she was not as capable as the older ones of finding food. I invariably observed that the grown woman performed her work in an earnest and careful manner, and did not permit herself to be disturbed.

It is not uncommon for an Australian to inherit a wife; the custom being that a widow falls to the lot of the brother of the deceased husband. But the commonest way of getting a wife is by giving a sister or a daughter in exchange. Marriage may be either exogamous or endogamous. I have previously stated that it is usual to steal one another's wives; but it should be added that this, as a rule, occurs among the smaller families or sub-tribes, and but rarely among the larger tribes. A beautiful girl from another tribe was maltreated and killed not far from my headquarters. When I asked why they did not keep her rather than take her life in this manner, they said that they feared the strange tribe, to whose attacks they would continually be exposed if they kept the woman alive. Killing her would give less cause for resentment.

Willy and Chinaman always took into consideration the youth of their wives, and did not make them carry the large burdens usually laid upon women. Of course they had to fetch leaves and grass for the hut, run after water, and find larvae and fruits, and go on errands in general, but upon the whole they had an easy time of it, and their husbands gave them a considerable amount of food. Surely when they received the bag of food I mentioned before, their husbands must have been prompted by higher motives than simply the idea that the food would make them stronger, and therefore capable of doing more work.

In the evening, when Willy and Chinaman came back from their wives, they brought a basket of fruit from the poisonous palm Cycas media, which is called by the natives kadjera. When the nut is cracked, the kernel is subjected to an elaborate process of pounding, roasting, and soaking, until all is changed into a white porridge. Although my men were very fond of my fare, which I shared with them plentifully, still they felt a need of their own food. Kadjera constitutes during this season of the year, from October to December, the principal food of the blacks, tobola and koraddan, other fruits, being what they live chiefly upon from January to March. When the time comes for harvesting these fruits, the women set out together to gather and prepare them, and they are frequently absent from the camp for several days.

We had now exerted ourselves a long time, and suffered much fatigue from trying to secure a specimen of boongary, when all the men one day suddenly declared that nothing would induce them to hunt the boongary without a dog, and that there was no use in continuing the expedition. Though this was a great disappointment to me, there was nothing else to do but to return to my headquarters to get a dingo and more provisions.

On my arrival at Herbert Vale I also secured some new men. Among them Jimmy was especially noteworthy. He was a square-built, athletic fellow with a short neck and broad shoulders. There was a sinister expression in his face, and he was a man of few words. I also enlisted in my service another native, Mangola-Maggi, a smooth-haired young man who, in spite of his youth, was highly respected among the blacks on account of his ability to procure talgoro - that is, human flesh. This was certainly not the particular qualification that I sought. What I wanted was good hunters, and in choosing my men I had to pay special attention to this point without regard to other less desirable qualities.

I suggested that they should take their wives with them, and they were the more easily persuaded to do so as the women were going in the same direction to gather fruits, and the latter received orders to keep a sharp look-out for boongary, which during the day sleep in the high trees.

On our journey across the open country Willy and I led the way. In the afternoon some of my people remained behind to dig out a bandicoot, among them Lucy, Willy's wife. She had stayed without her husband's consent, and for this she must be punished. When, after about an hour, she overtook us, Willy, greatly enraged, asked her why she had remained behind, and at the same time picked up a large piece of wood and hurled it past her face. She did not dare to stir or hardly to blink with her eyes, and made no effort to ward off the projectile, knowing that her husband would become only more angry and try the more to hit her. As it was, he only threw the piece of wood several times to frighten her.

The bandicoot, which had given rise to this domestic scene between Willy and Lucy, I wanted for my collection; but Chinaman would not give it up. He was, on the whole, very selfish, passionate, and greedy. He twice told me that he liked the flesh of little children better than that of grown-up people, because the former were "so fat." When we had slain an animal the thought of eating was uppermost in his mind, and I often failed to secure rare specimens which he and his comrades had killed and eaten before I could claim them. It was therefore necessary not only to find and kill the animals, but also to save them from disappearing into the hungry stomachs of the blacks. Even though they knew that they would get tobacco for the animal, momentary enjoyment so predominated in their minds that they had no time to think of the tobacco.

We rose at sunrise the next morning, and continued the ascent. I had so distributed my baggage among the natives that the women carried the provisions and the men the gun and ammunition and the thighs of a wallaby, which I had taken as a lure for yarri. Saturated with strychnine, the flesh of the wallaby was exposed in various places along the river, particularly where brooks emptied into the latter, for here, according to the statements of the natives, the yarri were apt to be found during the night.

We worked our way up over large stones and among creeping vines, and toward noon approached the goal of our day's march, about 600 ft. below the level of the mountain summit. Before us we still had a very steep and difficult country to traverse, and we now halted near the confluence of two mountain brooks to get something to eat.

I had so planned that the women were to go for several days by themselves in another direction in order to search the scrubs, and at the same time gather fruits, while we were to follow the brook and make our camp on the summit of the mountain. The woods are so dense that a man cannot make a long journey in a day, and as it was of importance to investigate as large a region as possible, I hoped that the women would in this way be of great use to us. The men were, however, unwilling to agree to this plan, and they suggested instead not to send the women out until the next day, but to send them on now with the provisions and baggage to the proposed camping-place, while they and I were to make a digression to the south in order to look for boongary. We were to meet again on the top of the mountain. Their proposition seemed to me excellent, for in this way we might make a better use of our time, and so we set out, without any suspicion on my part of their treacherous intentions. As usual, it was not long before I was some distance behind my people, who during such ascents were wont to proceed much more rapidly than I did; my boots making it difficult for me to keep pace with them. Certainly I thought they were in a greater hurry than usual, but I paid no particular attention to this fact. Finally, I had only Chinaman and his dog before me. Our course along a little brook was very steep, and so narrow that we frequently had to creep on our hands and knees under the enormous fern-trees, in order to get through.

Presently Chinaman also disappeared in the scrub, and I suddenly found myself all alone with my dog "Donna." I shouted, but heard no answer, and it now dawned upon my mind that I was the victim of a plot. In order to get possession of my provisions, they had, of course, agreed on a place where they were to join the women, or perhaps they intended to meet at the place fixed upon for a camp, in order to feast on my food. I knew that they would not rob and eat everything, for like children who help themselves to sweets, they imagine that nothing will be discovered if only something is left, be it ever so little. There was danger, however, that my provisions would be consumed to such a degree as to make it impossible to continue the expedition. I had been careless enough to leave the food in two open bags, but had looked better after the tobacco, the latter being well packed in the centre of my baggage.

After a short time I heard them in the distance giving signals to the women. The only thing for me to do was to make an effort to proceed alone. I knew pretty nearly where we were to encamp, but it was not so easy to find the way through the scrub, where nothing is to be seen to guide the traveller.

I was several hours in reaching the summit. Meanwhile it had begun to rain, sunset was drawing on, and it was high time that I found the camp. At length I heard the blacks talking on the top of a little hill near by, and I soon found the place, a little opening in the dense scrub scarcely eight yards square, where they had already built their huts. It was a very convenient place for a camp, and I could see that it had frequently been used for this purpose, for on all sides there were large heaps of fruit husks.

I at once commanded them to produce the provision bags, and discovered to my satisfaction that they had consumed less of the contents than I feared. When I asked them why they had abandoned me in order to steal the provisions, they answered that they had been very much afraid that the white man would get lost, but added, in an ingratiating manner, that they were now going to make him a good hut. The only way to punish them which was left me was to shoot one of them, and I therefore let the matter drop, but gave them to understand that if the offence was repeated I should use the revolver. I then ordered them to build a hut, as it was already night and the rain was increasing. From this incident it is clear that it is not true, as many maintain, that the Australian native is guided wholly by his instincts. I am willing to admit that his reasoning powers are but slightly developed, as he is unable to concentrate his thoughts for any length of time on one subject, but he can come to a logical conclusion, a fact which has been denied.1

1 See, for example, Transactions of Royal Society of New South Wales for January 1883.

In a few minutes my hut was ready. It made me feel depressed to be alone with the savages in such a stormy night. The fog was dense, and it was so dark that we could not see our hands before our eyes. As my hut stood in the centre of those of the natives, I had built a fire on either side, and in order to keep close watch of them I made two entrances. I was tired, and soon fell asleep.

Later in the night a most violent shower of rain suddenly fell upon us; the water poured through the roofs of our huts and put out the fires. I awoke in inky darkness and heard the natives groaning in their disgust at this unexpected shower-bath on their naked bodies. I got up and drew my woollen blanket close around me and waited for the dawn of day.

Long before daybreak the natives began making fresh fires, and with their remarkable skill in this respect they soon had a fire kindled in front of each hut. By constructing a sort of shed of palm leaves they succeeded in keeping them alive through the night. Every now and then they had to go out into the scrubs and gather pieces of bark or dry rubbish from hollow trees. Our huts became united, as it were, by these little sheds under one roof, and the result was that we were considerably troubled by smoke.

It is most delightful to be able to stretch one's wet and tired limbs by the fire even in the hut of a savage, and to be warm and cosy while the rain pours down outside. To the Australian the fire is, of course, of great importance, for with him it takes the place of clothes in cold weather. On Herbert River the natives, as before stated, go naked all the year round. The women, and particularly the older ones, may occasionally be seen covered with a mat made from the inner bark of the tea-tree, and this mat was also sometimes used on the floor of the hut. They wear it over their shoulders, but it scarcely does more than cover their shoulder-blades, like a lady's cape. The skins of animals are never used as mats or clothes.

During the two or three days that we stayed here the blacks spent most of the time in sleeping and eating. The women mended the fires and repaired the roofs where they leaked. I was busy much of the time drying my clothes. I hung them in front of the fire, and in the course of a day they were sufficiently dry to put on. As exercise in the open air was out of the question, I had to spend these days in my hut either in a reclining or a sitting position, and, like the blacks, tried to pass the time by sleeping. The unceasing rain soon destroyed the roofs of our huts, so that both the men and the women had to repair to the scrub and get more palm leaves. They also made a little trench round each hut to carry the water away, but they were usually idle. When they did not sleep they continually demanded food and tobacco; the men had some right to do so, but the women had no claim on me, for it was originally agreed that they were to accompany me at their own expense. They had also brought with them their own food, consisting of the usual unpalatable plants and fruits.

My people had noticed that I took my meals - breakfast, dinner, and supper - regularly, and this had given rise to their habit of asking for food at the same time and of applying civilised names to the meals. Savages live irregularly, and eat when they are hungry. It was curious to hear them demand "breakfast," "dinner," and "supper," even if they had just been gorging themselves with their own food. During these days I scarcely heard any other words from their lips.

I was astonished to see the men on this occasion give the women a part of their rations, and what particularly surprised me was that they gave them more than they kept themselves. The native likes to assume a liberal air, sometimes even towards his wife; for a person bestowing gifts right and left is looked upon as a great man. Thus it is the custom for a man who has slain a wild animal to eat but little of it himself, and to distribute it freely among his comrades, whom he watches with satisfaction while they prepare and consume his game. This chivalry towards the fair sex was an annoyance to me, for my provisions were not over abundant.

As the rain continued some days longer, I was obliged to call the attention of the blacks to the fact that my provisions were nearly consumed, so that they must look for their own food. Two of them did go out, and soon returned with a few larvae and some young shoots of the palm-tree. This was all the effort considered necessary to supply themselves with food for a whole day. These shoots consisted of the fresh buds of the Ptychosperma cunninghamii [Archontophoenix cunninghamii]. It was roasted in the ashes, but is usually eaten raw. I could not eat it, for it has an insipid and revolting taste even when boiled in water.

One day, as I went outside the hut to stretch my cramped legs, I discovered in the fog a bird which acted in a singular manner. While sitting on a branch it raised its wings, twisting its body to either side, in which position it looked like a cormorant drying its wings. I shot it, and the blacks fetched it to me out of the scrub. It was an Australian bird of paradise, the celebrated Rifle-bird (Ptiloris victoriae), which, according to Gould, has the most brilliant plumage of all Australian birds. It is difficult to determine its colour, as its velvet-like plumage assumes the most varied tints according as the light falls upon it.