Respect for right of property - New country - My camp - Mountain ascent - Tree-ferns - A dangerous nettle - A night in a cavern - Art among the blacks - Eatable larvae - Omelette aux coleopteres - Music of the blacks - Impudent begging.

I was now to make an expedition to Willy's much-lauded country, taking both him and his friend Chinaman into my service, and retaining some of my previous companions. On account of the recent borboby, several of my men were supplied with swords and spears. As they would have no use for them, they hid them in the course of the day under a bush for some other occasion. I never heard of such things being stolen from them. They always left them in the fullest confidence that they would find them again. The contrary is the case with provisions, which they sometimes conceal in this manner; every man will take what food he can lay his hands on. There is, however, considerable respect for the right of property, and they do not steal from one another to any great extent.

If, for instance, a native finds a hive of honey in a tree, but has not an immediate opportunity of chopping it out, he can safely leave it till some other day; the discoverer owns it, and nobody else will touch it if he has either given an account of it or marked the tree, as is the custom in some parts of Western Queensland. If they hunt they will not take another person's game, all the members of the same tribe having apparently full confidence in each other. Thus the right of property is to a certain extent respected; but least of all, as has before been pointed out, when it concerns their dearest possession - the women. But it is, of course, solely among members of the same tribe that there is so great a difference between mine and thine; strange tribes look upon each other as wild beasts.

The road was very difficult. We climbed hills and marched through deep valleys, and sometimes had to fell the trees in order to get through. I was surprised to see how quickly the blacks cut down the trees with their tomahawks. Though I was stronger than they, still they brought a tree down more rapidly, because they understood how to give the axe more force. After riding for some time up a grassy slope, which at length became perfectly level, we suddenly caught sight of a broad and long scrub-grown mountain valley, through which there flowed a river, which now foamed in rapid currents and now fell over high precipices, forming magnificent waterfalls. The roar of the waters and the dark green vegetation clothing the hills on both sides of the valley from base to top made me cheerful, and awakened in me hopes of interesting finds. Against the dark green background the palms stood out in strong contrast among the lower parts of the scrub. There were great numbers of these stately trees, with their bright, glittering crowns towering far above the rest of the forest.

An air of indescribable freshness seemed to breathe upon us as we entered the last grassy plateau. Willy proposed that we should build our huts in a different manner from what we had done before. His motive was, of course, laziness, for he wanted to avoid fetching palm leaves from the scrub, but his proposition was a fortunate one, for I thereby obtained a more solid hut than I should otherwise have had. He hewed the stems of some slender trees, and made four short fork-shaped stakes, the lower ends of which were sharpened so as to be easily driven into the ground. The stakes were put in a square, and were scarcely a yard high. In the forks long branches were laid, and over these the roof was made with more branches and long dry grass. I made myself a very comfortable bed of leaves and grass, spreading a mackintosh over the latter, and using some of the things I carried with me for a pillow; among these was my dearest treasure - the tobacco. By my side was my gun, which was always my faithful bedfellow.

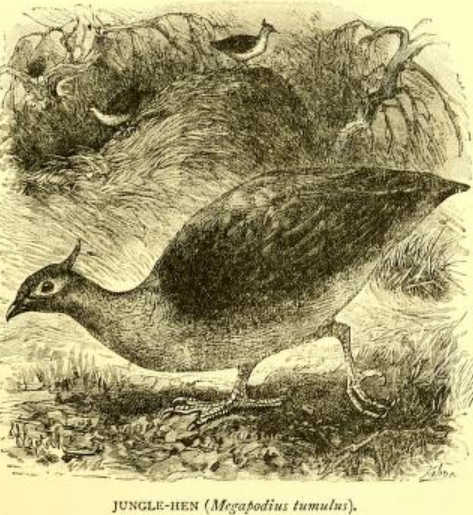

While we were occupied in making the huts. Chinaman had disappeared. He soon returned with a large number of jungle-hens or grauan (Megapodius tumulus), a name applied by the natives both to the bird and to its eggs. This was Chinaman's own "land," and so he knew every spot in the forest, and particularly all the mounds in which jungle-hens' eggs were to be found. November was just the time for the grauan, which is found in great abundance in the lower part of the scrubs, but not higher up, where the cootjari (Talegalla) takes its place.

The eggs are about four times the size of hens' eggs, and are prepared and eaten in the following original manner: The blacks, having first made a hole on one side of the egg, place it on the hot ashes, and after a minute or two the contents begin to boil. Two objects are gained by making a hole in the egg - in the first place it does not break easily, and in the second place it can be eaten while lying boiling in the ashes. They dip into the egg the end of a cane that has been chewed so as to form a brush, and use this as a spoon.

As is well known, the jungle-hen, like the brush-turkey (Talegalla), hatches her eggs by the aid of artificial heat. She lays the eggs in a large mound, which she constructs herself from earth and all sorts of vegetable debris; and the heat generated in the mound by the fermenting of the decaying vegetable matter is sufficient for hatching the eggs. Several females use the same mound, and the eggs being laid at long intervals, they are, of course, in different stages of development. As a rule there are chickens in them, but far from being rejected these eggs are preferred to the fresh ones. If the chicken is about half developed and lies, so to speak, in its own sauce, the natives first eat with their "spoons" the white, and what remains of the yolk, and then the egg is crushed and the chicken taken out. The down having been removed, the chicken is laid on the coals, and then eaten - head, claws, and all.

The next day we made our ascent along the river. We had to wade most of the time. The natives made the most remarkable progress, stepping lightly on the stones, while I with my shoes on could scarcely keep pace with them. It was a long and difficult road to travel. Weary and thirsty, I often stooped to drink the cool water, and to bathe my head in it. But I was cheered by the sight of the luxuriant and beautiful surroundings. Trees and bushes formed a wall along the mountain stream, overhanging the babbling water. In the woods all was dark and damp, but on gazing upward I saw the tree-tops flooded with the most brilliant sunlight, which occasionally penetrated through the branches, and above us was spread the sky in an infinite expanse of azure blue. Occasionally among the trees I caught a glimpse of the hills, rising on both sides in a mass of green of the most varied shades and tints. Here and there could be seen the tall slender stem of the common Australian palm, or of the fan-palm with its large glistening leaves.

Now and then we startle from its branch the beautiful little indigo blue and red kingfisher (Alcyone azurea), which with quick wing-strokes flies before us up the stream. Among the tree-tops the large brilliant blue or green butterflies (Ornithoptera) flutter. In the water pools were seen numerous crawfish, which the natives are fond of spearing with a stiff palm branch sharpened at one end, which they thrust down to the creature, at the same time uttering a low babbling sound to attract its attention. The crawfish takes hold of the stake; a quick thrust with the nimble hand of the black man, and it is pierced by the point.

As we ascend, the landscape gradually grows wilder and more picturesque. The river gorge becomes narrower, the amount of water diminishes, and no more kingfishers are seen. The palms are replaced by gigantic tree-ferns, which here, in the damp rocky clefts, spread their mighty leaves in all their splendour over trickling brooks, which frequently disappear in little waterfalls down steep precipices. To form an idea of the size of these ferns I broke off one of the secondary leaves, and found that it reached up to my chin, but I saw several that were much larger. The effects of light and shade are magnificent here, the scenery is simply overwhelming in its splendour, and yet there is no one to admire all this beauty save the blacks, who do not comprehend it!

Thus approaching the end of our day's march, and making our way up among the rocks, Willy, who led the way, suddenly stopped, and gave me to understand that I must come to him quickly with my gun. But before I got half way the animal had disappeared. It was a young yarri, which he had frightened up from its lair only a few steps away. Willy might have killed it with his tomahawk, but neglected to do so, as he had contracted the habit of thinking that everything must be shot with the gun, in whose fatal and unerring influence my blacks had acquired great confidence, and for this reason they usually left it to me to kill the game we happened to find. On account of Willy's stupidity we this time failed to secure this rare animal. Then we had a difficult march over debris of round stones or in thorny scrubs. Among these thick masses of stony debris there grew tall, slender, foliferous trees, and here it was that my blacks expected to find boongary; for the leaves of these trees are their principal food. Where no trees grew, creeping plants covered the debris like a carpet, which made walking dangerous, for the stones would roll away, while our feet stuck fast in this net of climbing plants.

On the summit we also meet with scenes of a wholly different character. Here is the real home of the lawyer-palm, which grows on small hills, where the soil consists of a deep black mould, and consequently is so fertile that it produces everything in the greatest abundance. Progress is difficult here, because this palm grows into immense heaps twenty to twenty-eight feet high, one by the side of the other, and often firmly woven together. In this way large connected masses are formed, appearing like an impenetrable wall. But the native usually finds a narrow passage, through which he can crawl, but not without getting badly scratched.

In this dense and pathless forest the boongary has his home, and we found many traces of the animal, some of them quite recent, both on the high slender stems and on the smaller trees of the scrub.

Working our way up the side of the mountain near the summit, the natives called my attention to an animal the size of a cat, which ran about in the branches of a tree. They called it toollah. It was late in the afternoon when I killed this animal, which proved to be a kind of opossum now known in zoology by the name of Pseudochirus archeri; it has a peculiar greenish-yellow colour with a few indistinct stripes of black or white, and thus looks very much like a moss-grown tree-trunk. Though it is a night animal, it also comes out about three or four o'clock in the afternoon, and is the only one of the family which appears in the daytime.

One of the greatest annoyances in this almost inaccessible region is the poisonous nettle, the stinging-tree (Laportea moroides). It is so poisonous that if its beautiful heart-shaped leaves are only put in motion they cause you to sneeze. The fruit resembles raspberries in appearance, the leaves are covered with nettles on both sides, and a sting from them gives great pain. It will make a dog howl with all his might; but it has an especially violent effect on horses. They roll themselves as if mad from pain, and if they do not at once receive attention they will in this way kill themselves, as frequently happens in Northern Queensland. The natives greatly dread being stung by this nettle, and always avoid it. If you are stung in the hand you soon feel a pricking pain up the whole arm, and finally in the lymphatic glands of the armpit. You sleep restlessly the first night. The pain gradually leaves the arm, but for two to three weeks you have a sense of having burned your hand if the latter comes in contact with water, for then the pain at once returns where you were stung by the nettle.

Still, I found the fear of this nettle to be exaggerated. If you at once put on some of the juice of the plant called Colocasia macrorhiza which resembles an arum, and which is always found growing near the nettle, the pain is soothed and the effect of the poison neutralised. This sharp white juice, which is itself poisonous, produces a violent smarting pain where the skin is thin, as for instance on the lips.

It is a remarkable fact that the antidote to this poisonous nettle always grows in its immediate vicinity, and I cannot help thinking of a parallel case, viz. kusso and kamala, the best remedies for tape-worm, which are found in Abyssinia, the home of the tape-worm.

One night we spent in a cave near the brook. I had some hesitation at first in spending the night in these scrubs, where the air is unhealthy and apt to produce fever. Four white men died in one week in the scrubs along Johnston river. But I assumed that I, being by this time used to the climate, could sleep there as well as the blacks, who did so without injury. Besides, the lower scrubs are surely much more unhealthy than those farther up the mountains, and I had never suffered any harm from stopping in them overnight. The cave was not large, and was low, cold, and damp, and thus not very inviting. We had but its naked stones for a couch, for there was of course no grass to be found in the scrub. A big fire was kindled; outside it was pitch dark.

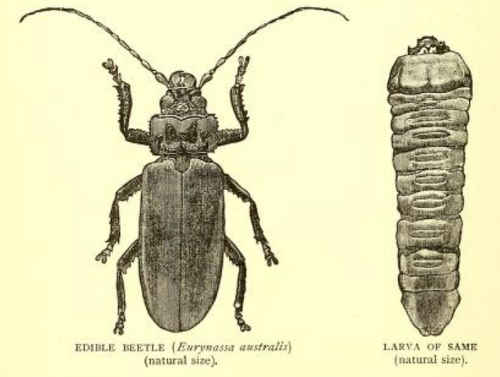

My blacks had found in a large fallen tree some larvae of beetles (Coleoptera), on which we feasted. There are several varieties of these edible larvae, and all have a different taste. The best one is glittering white, of the thickness of a finger, and is found in the acacia-trees. The others live in the scrubs, and are smaller, and not equal to the former in flavour. The blacks are so fond of them that they even eat them alive while they pick them out of the decayed trunk of a tree - a not very attractive spectacle. The larvae were usually collected in baskets and so taken to the camp. The Australian does not as a rule eat raw animal food; the only exception I know of being these Coleoptera larvae.

The large fire crackled lustily in the cave while we sat round it preparing the larvae. We simply placed them in the red-hot ashes, where they at once became brown and crisp, and the fat fairly bubbled in them while they were being thus prepared. After being turned once or twice they were thrown out from the ashes with a stick, and were ready to be eaten. Strange to say, these larvae were the best food the natives were able to offer me, and the only kind which I really enjoyed. If such a larva is broken in two, it will be found to consist of a yellow and tolerably compact mass rather like an omelette. In taste it resembles an egg, but it seemed to me that the best kind, namely the acacia larva, which has the flavour of nuts, tasted even better than a European omelette. The natives always consumed the entire larva, while I usually bit off the head and threw aside the skin, but my men always consumed my leavings with great gusto. They also ate the beetles as greedily as the larvae, simply removing the hard wings before roasting them. The natives are also fond of eating the larger species of wood-beetles. Some crawfish, moreover, were roasted, and had as fine a flavour as those in Europe; unfortunately there were not many of them.

In the strong light from the fire my eyes discovered on the roof of the cave some figures made by the blacks who frequented these regions: these figures represented a man and a woman with a baby. The drawing consisted merely of a few lines scratched with charcoal and red paint, and the figures had large spreading fingers and toes. They were upon the whole very imperfect, still not without symmetry; the left side was precisely like the right, but apart from this the figures were very irregular. The natives can draw pictures only of the crudest kind. I once showed them my photograph, but they had no idea of what it was meant to represent, or of how it was to be held; they turned it upside down and every other way, but the Kanaka, who was present, at once knew what it was. The civilised blacks, on the other hand, have a clearer notion of pictures, and easily recognise a person from a photograph.

In the morning we were roused by the lively singing of birds. Most prominent was the monotonous and persistent sound of a bird which the blacks call towdala, on account of its unceasing chattering. Its breast is reddish-brown; it is about as large as a quail, is very shy, and usually stays on the ground, moving very rapidly. This morning one was sitting on the other side of the river singing so persistently and so loudly that it irritated one of the natives, who tried to drive it away, throwing stones at it. The bird (Orthonyx spaldingii) is inseparably connected with the scrubs, and keeps up a lively song morning and evening. Though its song is monotonous, I always liked to hear its jubilant and happy voice.

In the sand along the stream the common "water-iguana" had laid its eggs, which are so well concealed that it is almost impossible to find them, but nothing escapes the keen eyes of the natives. Every now and then they dig out the eggs, which are not, however, very numerous in any one place. They also occasionally succeed in capturing the lizard itself, or in killing it by throwing sticks at it. It usually lies resting near the stream, but is very shy, and on being disturbed disappears into the water with a great splash. Both the lizard, which tastes like a chicken, and its eggs are eagerly eaten by the natives.

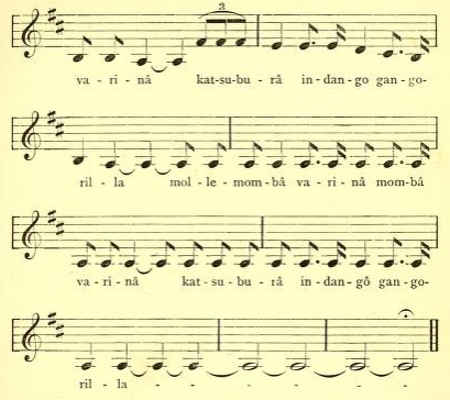

We spent several nights at our headquarters in this beautiful and invigorating mountain region. When we had eaten our supper and put all things to rights we laid ourselves round the fire, feeling very comfortable after the fatiguing journeys of the day. One of the natives then usually sang a song while lying on his back, accompanying himself with two wooden sticks. The song was, as usual, a ceaseless repetition of a couple of strophes, each one of which ended in a long monotonous series of deep tones by which the strophe was repeated. To be able to hold the last tone very long is a sign of ability to sing well. If a song has been known a long time in a tribe, it gradually loses its popularity, and gives place to a new composition, which is either original or borrowed from a neighbouring tribe. But they do not often have the opportunity of learning new songs, and consequently their repertoire is very limited. The song in vogue at this time, and which was sung repeatedly, was as follows:

It is a remarkable fact that they themselves sometimes do not understand the words which they sing, the song having been learned from a tribe which speaks another dialect. Thus a good song will travel from tribe to tribe. I heard the above-quoted song sung by "civilised" blacks near Rockhampton, 500 miles due south of Herbert Vale. Doubtless it originated in the vicinity of Rockhampton, and accordingly it must have travelled through "many lands" before it came to the savages in the mountains on Herbert River, where it was sung without being understood.

They rarely sing without accompaniment. The singer produces this by beating a boomerang against a nulla-nulla, the former hitting the latter with both ends, but not quite simultaneously. When weapons are wanting, pieces of wood are used. Sometimes they also have their own musical instrument. It is a somewhat thick piece of hard wood in the form of a club. But this, their only musical instrument, is rare, and I only saw it once on Herbert River.

The natives have a better ear for rhythm than for melody. Still I learned from them a few tolerably melodious songs, as for instance the one above quoted. They took no interest whatever in my songs. There was but one of them that they could appreciate at all, and this only when strongly accentuated, namely, Erik Bogh's: "I have sailed around the world, and I have walked many a mile." But I did not often attempt to entertain so unappreciative an audience.

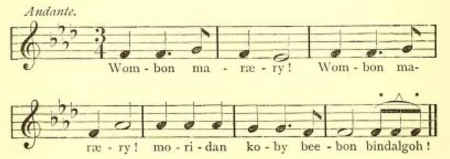

Their voices are hoarse, but never seem to give out. The singer in the camp usually sits with his legs crossed before the fire. As a rule only one, but sometimes two, sing at a time, accompanying themselves, but they never sing in chorus. A black man rambling among the trees alone may at times be heard making the woods echo with his joyful song. He feels free and happy in his native hunting-grounds. The following war-song, which celebrates the knob on the throwing-stick, I used to hear in the woods on Herbert river:

The women are also sometimes heard singing in the woods, but hardly ever in the camp. The Australian natives are gay and happy, but their song is rather melancholy, and in excellent harmony with the sombre nature of Australia. It awakened feelings of sadness in me when I heard it from the solemn gum-tree forest, accompanied by the monotonous clatter of the two wooden weapons.

My men were in good spirits on this expedition, and they sang nearly every night of their own accord. The sole cause of their happiness was that they received plenty of the white man's food. I had taken with me an abundance of provisions, and I distributed them liberally, on the false assumption that the more I gave them the better they would work. Though I had long been careful to give them nothing gratis, and always to demand work for what I bestowed, I had not yet learned to give them only fair compensation, for the more they get the more they want. To be liberal is simply dangerous, for they assume that the gift is bestowed out of fear, and they look upon the giver as a person easy to kill. Too great liberality demoralises them. They become exacting and disobedient, and finally treacherously assault the giver.

As long as they understand that they can have advantages from a white man, they let him live. The one thing which keeps them from killing him is fear.

After having received all the food they wanted they became lazy, and demanded a fuller compensation for their work. Their demands increased day by day, and were no longer limited to food, but gradually included the most unreasonable things, such as the clothes I wore, not to mention my weapons and the whole supply of tobacco.

One morning when Willy and I went out to get the horses, he boldly demanded the trousers I was wearing. When I positively refused to give them to him, he wanted to borrow them to protect himself from the dew on the grass, which he said annoyed him.

No matter how much they had eaten, they never said no when I, in excessive liberality, offered them more food. They laid by what they did not eat, but I did not scold them, for I was anxious to keep them in my service. It soon became plain to me, however, that I must take a different course if I wished to save my life.