Mongan, a new mammal - For my collection or to feed the blacks? - Natives do not eat raw meat - A young yarri - A meteorite - Fear of attacks - Cannibals on the war-path - The relations between the tribes.

The following day the rain had entirely ceased, but the natives refused to continue the journey because the scrub was so wet. Still I had determined to raise the disagreeable quarantine, even though I should expose myself to still greater discomfiture. After an hour or two I actually succeeded in getting them to start, in spite of Willy's assurances that it was impossible to get into the other valley for which I was making. Jimmy went alone upon some hills to find mongan, a mammal which the natives had mentioned to me, but which I had not yet seen. The women were excused from gathering fruits in the scrub, which was now scarcely accessible, and instead they were to go down to the grassy plain and examine the poisoned meat which we had laid there as lures for the yarri. The men accompanied me to a neighbouring valley, where the women declared they had seen boongary on one of their expeditions to gather fruit.

The long incessant rain had formed countless brooks, which, with their clear and sparkling water, frequently crossed our path to vanish in the dense scrub. The sky was now clear and cloudless, and the wet, dense forest lay bathed in the bright glittering sunshine, which produced an intense heat, while warm vapours rising from the ground and from the trees made the air so damp and oppressive that we became very much exhausted.

We often found large coils of the lawyer-palm obstructing our passage. Willy repeatedly called my attention to the fact that he had been right in urging that the scrub was impassable, but still we managed to get on, partly by going round, partly by creeping under the obstructions.

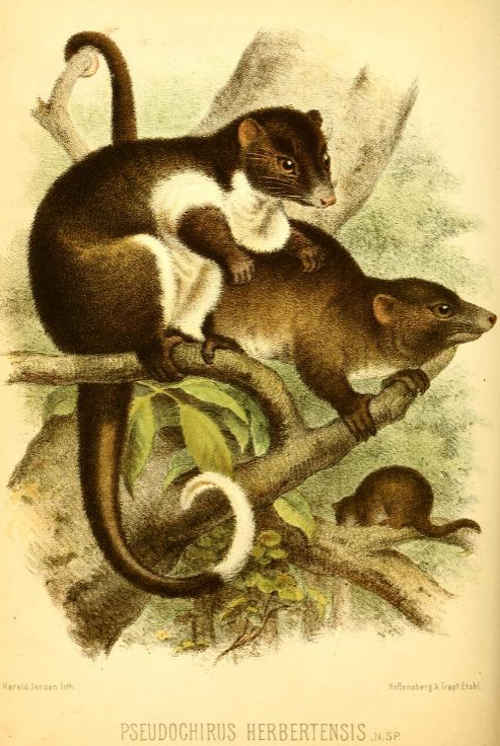

When we got out of the scrub we went along the side of a steep heap of debris overgrown with creeping plants, a difficult road, for the stones were continually loosened under our feet and rolled down with a tremendous crash. We saw nothing but old traces of boongary; on the other hand, I shot a specimen of the toollah (Pseudochirus archeri) described above. The dogs proved useless, my Gordon setter was, of course, too heavy to work in the scrub, to which she was not accustomed, and Chinaman's dog also disappointed my expectations, for it refused to range at all, thereby making its master so angry that he pelted it with sticks. We had agreed to meet the women and Jimmy at the foot of the mountains, and when we reached the camp at dusk we found them already there; they had inspected all the poisoned meat lures, but none of them had been touched. Jimmy, however, had, to my great delight, found mongan (Pseudochirus herbertensis), a new and very pretty mammal, whose habitat is exclusively the highest tops of the scrubs in the Coast Mountains (see coloured plate).

Willy and Chinaman persisted in having the toollah which I had shot, and as our provisions were giving out, I was obliged to surrender it, much to my chagrin. I tried to keep the skin, but they eagerly objected that the animal would lose its flavour if roasted without it. In order to satisfy their hunger, I was therefore obliged to give them both the skin and the body.

They now threw the animal on the fire, in order to singe the hair off. Then they cut its belly open with a sharp piece of wood, placed it on the coals, and as soon as it was half roasted it was torn into several pieces and distributed, hereupon each one roasted his share. In this way the Australian prepares and roasts all small mammals. He does not like to eat the meat raw, but has not the patience to wait until it is thoroughly done. As soon as a crust is formed on the meat, he takes it from the coals and gnaws off the roasted part; he then puts it back to roast the rest.

The women returned from their expedition with a lot of fruit rather like red peas, called by the natives koraddan. It grows on a climbing plant found in abundance in the scrub, but as a rule cannot be reached from the ground, hence the women must climb the trees to gather it. The koraddan is roasted between grass and hot stones, and has a comparatively good flavour, smelling and tasting like boiled peas.

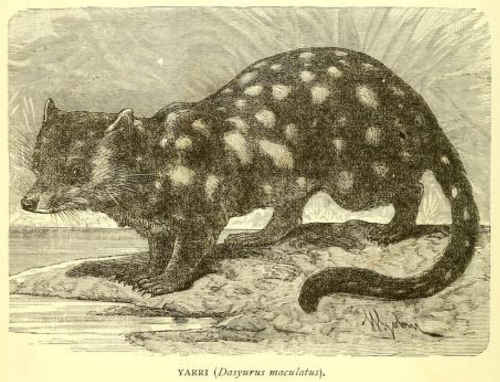

I had much trouble in getting the natives to look after the strychnine lures, in the effect of which they had no faith, as they are not in possession of any kind of poison. I promised them tobacco if they could bring me the animal I wanted. At last they started, and one day, to my great surprise, they brought me a yarri. The natives having a superstition that "a great water will rise" if a young man picks up a dead yarri, Jimmy, who was the oldest, had to carry the animal, and at the head of the others he brought it in triumph to the camp, holding it carefully by the tail high in the air. Had he not been present, I doubt whether I should have obtained the animal.

I concealed my joy, and in order to test them insisted that it was not a yarri that they had caught, but they shouted wildly yarri, yarri, yarri! declaring, however, that it was a young one. The skin was hardly three feet long from the snout to the end of the tail. It was of a yellowish-gray colour, with whitish round spots. It proved to be a Dasyurus maculatus, yarri being a name applied to the whole family of Dasyuridae. I am, however, convinced that there exists a large animal of this kind that has not yet been discovered. The one which the natives particularly call yarri I shall have occasion to mention farther on.

I was sorry to find that the specimen now brought to me had been lying so long that it had already become greenish on the under side, and had a bad smell. As my knives were rather blunt, it was no pleasant task to flay the animal, whose skin is very tough. Unfortunately my knife slipped and cut a deep gash in my thumb. To prevent blood-poisoning I applied caustic and carbolic acid, and continued my work with a bandage on my thumb.

One day I secured a specimen of the wonderful Hypsiprymnodon moschatus, which forms the connecting link between the kangaroos and the phalangers. This animal, called by the natives yopolo, is not very rare in the lower part of the scrubs, but is difficult to kill, as it haunts the banks of the rivers and is never seen on the grassy plain. When we walked along a river in the scrubs my blacks would often make a smacking sound that causes the animal, which is very curious, to come forth and thus be discovered. The yopolo is brown, and about the size of a stoat. Its lair is formed like a globular nest from fallen leaves near the root of a tree, but it is only to be discovered among the leaves and grass by the keen eyes of the blacks. The natives frequently succeed in catching the animal by placing their feet quickly on the lair, but as a rule the yopolo is hunted with a dingo.

The last evening but one of this expedition a very curious event happened. While we were eating supper we suddenly heard a terrible cry from the women, who had a camp by themselves farther down the river. After a moment's reflection the men ran down and soon brought the women up to our camp. A stone had been thrown against a rock close by, nearly hitting one of them, and this made them afraid of camping down there alone. They assumed that the stone had been thrown by strange natives, and they requested me to "shoot the land" to frighten them. When I had fired four or five times they thought they would be able to "sleep first-rate."

The next morning I went down to the deserted camp, and they at once pointed out to me where the stone had hit the rock with great force. Close by we also found all the pieces, which together formed a heavy stone about the size of a potato, and was, no doubt, a meteorite. The women had made a false alarm, and there was no danger on this occasion. But as a rule they have every reason for being on their guard, for the neighbouring tribes are continually on a war-footing, and they are always in danger of attacks.

Individuals belonging to the same tribe are usually on the best of terms, but the different tribes are each other's mortal enemies. Woe therefore to the stranger who dares trespass on the land of another tribe! He is pursued like a wild beast and slain and eaten. In connection with this it should, however, be stated that the small subdivisions of the tribes that live nearest the border are on amicable terms with their neighbours, and that accordingly the borders between the tribes are frequently very indistinct. The family tribes have well-defined limits, and as a rule they are on friendly terms with each other. I am hardly able to state the extent of a tribe. The one living around Herbert Vale owned an area of land which I should estimate to be about forty miles long and thirty miles wide. It was divided into many sub-tribes or family tribes, which lived within their own well-defined limits, the country within which was well known to them. Outside their borders they had no acquaintance with the country. This was one of the difficulties I had to contend with, as I soon found that a native outside his own "land" was of little or no service to me, for he there felt very insecure. The case was still worse when he entered the domain of another tribe; there he was utterly restless and timid.

In a family tribe there may be about twenty to twenty-five individuals, often less. How many such small divisions it takes to make a tribe it is impossible to say, as there exists no sort of organisation. They do not even have chiefs, and in this respect they differ from the natives in other parts of Australia, where there are sometimes even two chiefs in one tribe, usually an old man and a young man. It is probably not far from the truth to estimate a tribe at two hundred to two hundred and fifty individuals. On important occasions the old men's advice is sought, and their counsel is mostly taken by the whole tribe, but there is no restraint put on the liberty of the individual. When a camp is broken up, those who wish to follow, do so; those who prefer to go somewhere else or to remain, take their choice. In most cases, however, there is a wonderful consonance between them. The natives on Herbert River have not much use for a chief, as the tribes do not, as in Western Queensland, carry on open warfare with each other, but simply seek to diminish the number of their enemies by treacherous attacks.

The Australian rambles about in his woods all day long, free from care, though he always feels a secret fear of strange blacks. But when "the sun is near the mountains" (vi molle mongan), he is filled with anxiety and restlessness at the thought of the dangers which threaten him after darkness falls upon the earth. The least sound makes him suspicious; he shudders and listens, and whispers timidly to his comrades, Kolle! mal! - that is, Hush ! man ! When he has assured himself that the fear is unfounded, he soon recovers his balance, to be again frightened by the next suspicious sound. During the daytime a torn-off leaf or a footprint which he does not understand at once awakens his mistrust.