| Chapter 25 | Table of Contents | Chapter 27 |

Message sticks—The common origin of the dialects—Remarkably complicated grammar—The language on Herbert river—Comparison of a few dialects.

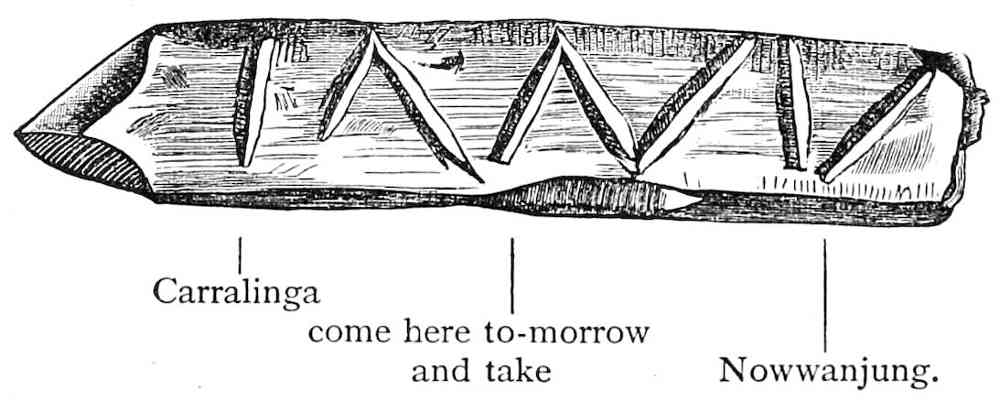

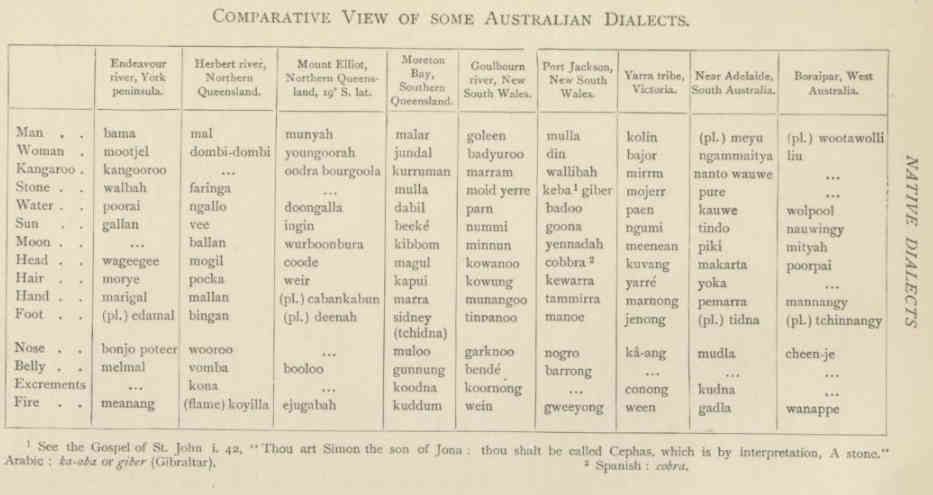

A race so uncivilised as the Australian natives has of course no written language. Still they are able to make themselves understood by a kind of sign language. Now and then the natives send information to other tribes, and this is done by the aid of figures scratched on a “message stick” made of wood, about four to seven inches long, and one inch wide. Some of them are flat, while others are round and about as thick as a man’s finger; they often are painted in different colours. I myself saw one of these sticks which came to a native among my acquaintances on Herbert river. The man told me that he understood the inscription perfectly well, and he even prepared a similar stick, on which he wrote an answer. The message stick shown on page is from Central Queensland. One side is meant to represent an enclosed piece of ground. There is a gate in the fence, and the dots mean grass and sheep. I am also fortunate in being able to give an illustration of another message stick (p. 304, with the interpretation of its inscription, which conveysa message from a black woman named Nowwanjung to her husband Carralinga of the Woongo tribe. Other message sticks are engraved with straight or circular lines in regular patterns as in embroidery; this has caused an entirely different view of their significance, which supposes them to be merely cards to identify the messenger. This view may be correct, but it is not corroborated by my experience on Herbert river.

Nearly every tribe has its own language, or at least its own dialect, so that the members of different tribes are unable to understand each other. The reason for this is to a great extent the hostility existing between the tribes. Of course every tribe is familiar with the language of its nearest neighbours, and makes use of nearly the same dialect when they talk with a friendly tribe, but they treat a hostile tribe with scorn, and ridicule their language. The language, not being written, is constantly undergoing change, and there is even a difference between the speech of the old people and the children. If you put the same question to a black man three or four times, his last answer will be expressed differently, though he uses the same words.

In spite of difference between the languages spoken in the various parts of the continent, an intimate relation is believed to exist between them, and it is the prevailing opinion that they spring from a common root language. At all events it is a fact that many words are the same in very large districts, even in places so far apart that they cannot possibly have influenced each other by communication. I know a case where a black man from Clermont understood the language spoken in Aramac and on Georgina river, and yet he had never been there.

This similarity of vocabulary must not be confounded with those words which are used everywhere, and which have been spread by Europeans. Many of these are not Australian in their origin. The colonist, who moves from one part of the country to another, generally takes with him some of the words of the language of the blacks, and thus these are transplanted into new soil. In this manner many words have emigrated from Victoria and New South Wales, and have taken root with the new civilisation. There are now a number of such words which are in vogue throughout the civilised part of the continent—for example, yariman, horse; dillibag, basket; kabra, [18] head; bingee, belly; gin, woman; gramma, to steal; bael, not; boodgary, excellent; korroboree, festive dance; dingo, dog, etc. We can even trace words which the Europeans have imported from the natives of other countries—for example, picaninny, a child. This word is said to have come originally from the negroes of Africa through white immigrants. In America the children of negroes are called picaninny. When the white men came to Australia, they applied this word to the children of the natives of this continent.

18. According to a word-list from the beginning of the century this word was used in Port Macquarie (cahbrah), and Port Jackson (cabbra).

Such “civilised words, however, seldom take root in the language of the blacks. They simply use them in conversation with the white man. Though a few words are carried in this manner from one district to another, this method of transplanting is not of any great importance.

A natural affinity between the languages can with certainty be pointed out. Some words are almost identical throughout the continent. An excellent illustration of this is found in the word for eye.

In Caledon Bay, on the Gulf of Carpentaria, it is mail; Endeavour river, on the north-west coast (16° S. lat.), meul; Moreton Bay (29° S. lat.), mill; Port Macquarie (33° S. lat.), 68 miles south from Sydney, me; Port Jackson (Sydney), mi or me; Limestone Creek (140 miles west of Sydney), milla; Yarra tribe, Victoria, mii; King George Sound (south-west coast, 35° S. lat.), mil; Herbert river (18 S. lat.), mill.

An equally interesting example is found in the numeral 2, which is tolerably constant throughout the continent—bular, bulara, buloara, budelar, burla, bulla, buled, boolray, pulette, pular, pollai, bolita, bulicht, bollowin, etc. Even in Tasmania the word is found, pualih. The words for 1 and 3 are, on the other hand, always different. For comparison I give the following table—

| Numerals. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Near Adelaide, South Australia | kumande | purlaitye | marnkutye | purlaitye-purlaitye | |

| Moreton Bay, Southern Queensland | ganar | burla | burla ganar | burla burla | korumba (much) |

| Boraipar, West Australia | keiarpe | pulette | pulekvia | pulette-pulette | |

| Burapper, S. E. Australia, near Murray river | kiarp | bullait | bullait-kiarp | bullait bullait | |

| Mount Elliot, Northern Queensland, 19° S. lat. | woggin | boolray | goodjoo | munwool | murgai |

| Tasmania, south coast | marrava | palih | wullyava | ||

A common root can also be shown in the personal pronoun. I is called ngaia, nganya, ngatoa, ngaii, ngai, ngie, ngan, ngu, ngipa, ngâpe, etc. Thouinta, nginta, nginte, nginda, ngin, ninna, nindu, nginne, etc.

Upon the whole, though the various languages have but little in common, there are certain peculiarities which may be regarded as characteristic of them all. They are polysyllabic, the accent is usually on the penultimate or antepenultimate, and the words are, therefore, not unpleasant to the ear. Indeed, many of them are full of euphony and harmony. The large number of vowels contributes much to this result. Guttural sounds are particularly prominent. The s sound appears to be very rare. On Herbert river I heard only two words which contained the letter s—suttungo, tobacco, and sinchen, syphilis, and so far as I know, s is found only in the beginning of words.

In grammar the languages also differ widely. At all events, the authors who have sought to discuss these matters thoroughly have arrived at very different results.

Mr. Beveridge, who has studied the languages of Victoria, claims that the syntax is very simple, saying that the various grammatical relations are expressed solely by prolongations, accentuations, and changes of position of the words. Mr. Lang, on the contrary, holds an entirely different opinion. He supports the popular theory that the Australian natives have in the past occupied a much higher plane of civilisation than at present, and thinks he is able to find traces of a decayed civilisation in the languages of the tribes, which in his opinion are very perfect.

As a striking example he mentions the inflections of the verbs. At Moreton Bay the verbs have far more inflections than the verbs in the Hebrew language. They can be conjugated reflexively, reciprocally, frequentatively, causatively, and permissively. They have not only indicative, imperative, and subjunctive, past, present, and future, expressed by definite inflectional endings, but each one of these endings may assume distinct shades of meaning expressed by different inflections. The imperfect of the verb to speak (goal) has not only a form which means “spoke,” but forms which mean “spoke to-day,” “spoke yesterday,” “spoke some days ago,” etc. The same is the case with the future. There are three imperatives: (1) speak; (2) thou shalt speak (emphatic); (3) speak if you can, or if you dare (ironical). The nouns are regularly inflected by suffixes; ngu means of, go to, da in, di from, kunda with, etc. The pronouns have both dual and plural form: ngaia I, ngulle we two, you and I; ngullina (comp. Herbert River, allingpa) we two, he and I, etc. This complicated syntax is found in many tribes, though they may have widely different languages.

Mr. E. M. Curr, of Melbourne, has recently in a great and very meritorious work, The Australian Race, pointed out 308a most striking resemblance between the languages of the Australian blacks and those of the African negroes. His opinion is that the Australian natives are descended from the African negroes by a cross with some other race. He admits that the Australian blacks look quite different from the natives of Africa, but he shows that the customs, the superstitions, and above all the languages, agree in many respects in a most remarkable manner. He points out the striking fact that while the Papuan and the Australian languages are almost totally different, still many of the words used by the Australian blacks are almost identical with those employed by the negroes of Africa.

The language of the natives on Herbert river is imperative and brief. A single word frequently expresses a whole sentence. Will you go with me?” is expressed simply by the interrogation nginta? (thou?), and the answer, “I will stay where I am,” by karri ngipa (I remain). “I will go home,” ngipa míttago (literally, I in respect to the hut).

The suffix go literally means “with regard to,” and is usually added to nouns to give them a verbal meaning, but it is also sometimes added to verbs. The question Wainta Morbora?—that is, “Where is Morbora?”—can be answered by saying only títyengo (he has gone hunting títyen) (wallaby), (literally, with respect to wallaby); or, for example, mittago he is at home (literally, with regard to the hut). Mottaigo means he is eating (literally, with regard to eating). “Throw him into the water,” is expressed simply by ngallogo. As is evident, this is a very convenient suffix, as it saves a number of moods and tenses. It may also be used to express the genitive—for example, toolgil tomoberogo, the bones of the ox.

There frequently is no difference between nouns, verbs, and adjectives. Kola means wrath, angry, and to get angry. Poka means smell, to smell, and rotten; oito means a jest, and to jest.

“It is noon,” is vi ōrupi (sun big). “It is early in the morning,” is vi naklam (sun little). “It is near sunset,” is vi molle mongan. Kolle is a very common word. It is, in fact, used to call attention to a strange or remarkable sound, and means “hush!” Kolle mal! “Hush, there is a strange man!” Klle is also used to express indignation or a protest, “far from it.” A superlative of an adjective is expressed by repetition—for example, krally-krally, “very old.”

The vocabulary is small. The language is rich in words describing phenomena that attract the attention of the savage, but it lacks words for abstract notions. The natives, being utterly unable to generalise, have no words for kinds or classes of things, as tree, bird, fish, etc. But each variety of these things has its own name. Strange to say, there are words not only for the animals and plants which the natives themselves use, but also for such as they have no use for or interest in whatever. On Georgina River the natives have a special word for sweetheart.

On Herbert River I found, to my surprise, various names for flame and coals. Vákkun meant camp fire, coals, or the burning stick of wood, while the flame was called koyílla.

Of numerals the Australian natives have no comprehension. Many tribes have only two numerals, viz. 1 and 2, and by combining these they can count to five, thus—1 keiarpe, 2 pulette, 3 pulette-keiarpe, 4 pulette-pulette, 5 pulette-pulette-keiarpe. Several tribes have three numerals, as, for instance, Herbert Vale tribe—1 yóngul, 2 yákkan, 3 krbo, 4, etc., is usually expressed by taggin (many). Occasionally a tribe may be found which has a word for 10. The word literally means two hands (bolita murrung), a remarkable parallel existing in many other languages (from the Sandwich Island to Madagascar) in which the word lima means both hand and five.

The dialects of the natives abound in proper nouns. Every locality has its name, every mountain, every brook, every opening in the woods. Many of these names are remarkable for their euphony. As a curiosity I quote the following stanza—

“I like the native names as Paramatta

And Illawarra and Woolloomoollo.

Toongabbe, Mittagong, and Coolingatta,

And Yurumbon, and Coodgiegang, Meroo,

Euranarina, Jackwa, Bulkomatta,

Nandowra, Tumbarumba, Woogaroo;

The Wollondilly and the Wingycarribbee,

The Warragumby, Daby, Bungarribee.”

It is a strange fact that the dialects in a great part of the country are named after their respective negatives. Wiraiaroi is a dialect in which wirai means “no,” and Wailiwun is one in which wail means “no.” Thus Kamilaroi, Wolaroi, etc. Pikumbul is an exception. In this dialect piku means “yes.” One cannot help thinking of the French Langue d’Oc and Langue dOyl.

| Chapter 25 | Table of Contents | Chapter 27 |