Winter in Northern Queensland - Snakes as food - Hunting snakes - An unexpected guest at night - Yokkai's first dress - Norway's "mountains of food" - Departure from Herbert Vale - Farewell to the world of the blacks.

Winter had now set in in earnest. The fields were gray, and the sun had lost much of its power. During the daytime it was still quite warm, though the heat was not oppressive. A more agreeable temperature than Northern Queensland during this season of the year can scarcely be conceived, especially toward sunset. I felt perfectly comfortable in my shirt sleeves without any vest. During the night so much dew falls that the woollen blanket becomes saturated if one sleeps beneath the open sky. Walking in the grass in the morning is almost like wading in a river. One becomes drenched to the hips. But what glorious mornings! They stimulate a person to work, and their freshness awakens all the joys of life.

The scrubs are very still in winter, and it is this stillness that gives the season its peculiar character. While the mammals and birds have donned their most beautiful and warmest furs and plumage, the natives go about as naked as in the summer. Not even in the night do they wear clothes, but warm themselves by the camp fires. Yet it is easy to procure subsistence during this season of the year. Fruits are not so abundant, but, on the other hand, animal food is easily obtained. During this season the natives are much occupied in hunting snakes, which during the winter are very sluggish, and can be slain in great numbers. The blacks are particularly fond of eating snakes, but they do not, like many of the southern tribes, eat poisonous serpents.

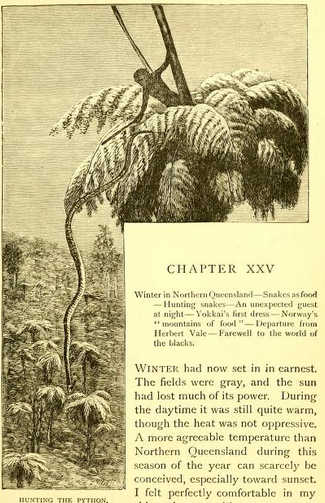

One of the snakes most commonly eaten is the Australian python (Morelia variegata), the largest snake found in Australia, which here in Northern Queensland may even attain a length of more than twenty feet. During winter it seems to prefer staying in the large clusters of ferns found on the trunks of trees. At night it seeks shelter from the cold among the leaves, but during the daytime it likes to bask in the sunshine, which enables the natives to discover and kill it with their clubs. If attacked it may bite with its many and sharp teeth, but the wound produced is not dangerous. These ferns grow in wreaths round the large trunks of trees, and look like the topsails of a ship, but they are far more numerous, and like the orchids, which grow pretty much in the same manner, are constant objects of interest to the natives, for in them they find not only snakes, but also rats and other small mammals, Uromys, Sminthopsis, Phascologale, etc. They therefore, as a rule, take the trouble to climb the trees to make the necessary search. They discover the snakes at a great distance, though the wreath may be fifty to sixty yards above the ground.

We were at one time travelling along one of the mountain streams, while the blacks as usual kept a sharp look-out and examined the numerous clusters of fern in the scrub. Suddenly they discovered something lying on the edge of one of these fern clusters, but very high in the air. Notwithstanding their keen eyesight, they were unable to make out whether it was a serpent or a broken branch, so a young boy, whom I usually called Willy, climbed up in a neighbouring tree to investigate the matter. Ere long he called down to us, Vindcheh! vindcheh! - that is, Snake! snake! I was very much surprised, for the object looked to me like an old leafless limb of a tree. Willy came down at once, and lost no time in ascending the tree where the serpent was lying.

When he had obtained a foothold near the fern wreath, he broke off a large branch and began striking the serpent, which now showed signs of life. The lazy snake soon received so many blows on the head that it fell down, and proved to be more than ten feet long. While we were taking a look at it we heard Willy, whom it was almost impossible to discover so high up in the tree, call down that he had found another snake, and this made the blacks jubilant.

It seemed, however, to be more difficult for Willy to get this snake down, for it was protected among the leaves, and he was obliged to use his stick with all his might in order to drive it out. At last it tried to make its escape, and crept out over the edge of the wreath of ferns in order to lay hold of the tree -trunk, but the distance was too great, and it slipped. It could not get back, for Willy stood there striking it, and so this serpent, which was more than sixteen feet long, fell off; in coming down it struck the crown of a palm-tree, which broke its fall, and quick as lightning, it coiled itself round the trunk of the tree like a corkscrew. Willy did not give up. He came down, and immediately climbed up in the palm-tree to his victim, which was, however, so tenacious of life that it did not let go its hold until its head was crushed.

When we came to look for the former serpent we were astonished to find it gone. We all searched carefully everywhere among the stones on the bank of the river, but it was not to be found, and we had given up the search when Willy, to our surprise, came dragging it behind him. He had found it at the bottom of a hole in the river, and had dived after it.

These serpents are wonderfully tenacious of life. The one in question was apparently dead and motionless when we left it, still it had been able to crawl twenty paces, and keep itself hidden at the bottom of a hole in the river-bed.

The natives, being anxious to secure themselves against other mishaps of this sort, decided to roast the serpents at once. But, as we had not time for this, they procured a withy band from a lawyer- palm, tied the two together until we returned in the evening, and made them fast to a tree, round the trunk of which the serpents coiled themselves. When we passed the place in the afternoon there was still life in them, but they were soon despatched, put together in bundles, and carried to the camp to be roasted for supper.

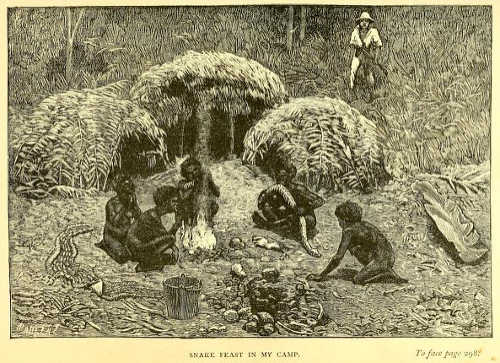

As quickly as possible the camp fire was made and stones were heated; for snakes are one of those delicacies which are prepared in the most recherche manner. The snakes were first laid carefully in circular form, in order that they might occupy as small a space as possible; each forming a disc fastened together with a reed, they looked like the rope-coils made by sailors on the deck of a ship. Large serpents, and the flesh of fish, cattle, and men, are all prepared in the following interesting manner. First a hole is made in the ground about a foot deep, and in it a great fire is built. Over the fire a few stones about twice the size of a man's fist are placed. When the stones have become red-hot, they are laid aside and the rest of the fire is cleared away. Then a number of the stones are put down into the hole, and over them are laid fresh green leaves, especially of the so-called native ginger (Alpinia. caerulea). Upon these the meat is placed, and is covered with leaves and with the rest of the hot stones; the dug-out earth is then spread over the whole, which has the appearance of an ant-hill. If an opening is discovered letting out steam, it is immediately covered so as to keep the heat within the hill.

Now the baking is permitted to go on undisturbed. The natives know precisely when the meat is done, and they never make a mistake. The hot stones have developed an intense heat, which gradually bakes or roasts the food thoroughly and preserves all its flavour.

On opening the mound the outer leaves are found to be scorched, while the inner ones are fresh and green, and give the dish a very inviting appearance. Beef prepared in this manner has a very fine flavour. If leaves of the ginger-plant are used, they give the food a peculiar, piquant taste. While I lived among the savages I adopted this manner of preparing my salt beef, after leaving it in a brook over night to get rid of the saltness.

No one who has never tasted meat prepared in this manner has any conception of what an excellent flavour it has. The principle is much the same as that applied in France, of roasting birds in clay; and in America, of baking clams. In my opinion, fishermen and hunters should adopt this method of preparing their meat. Large leaves are not necessary - common grass may be used, but it must be fresh and green, and must be put on in thick layers.

The Australian native does not take so great pains with common meat, but simply roasts it on the fuel or in the hot ashes. In this manner he also prepares his larvae, beetles, birds, lizards, and eggs. His fish he wraps up in leaves, and then roasts it in the ashes. The natives never use boiling water in preparing their food, hence they have no kettles. Food is not kept in a raw state, but is always roasted before it is put away. There is, however, rarely anything to save.

When the serpents were done and were taken out of the hot leaves, they were perfectly whole as before. The bands were loosened, and the snakes stretched out to their full length and cut open along one side with one of their own jaw-bones. First the fat is taken and handed in long strings to the greedy mouths; then the heart, liver, and lungs; finally the body itself is to be divided. As the jaw-bone is not a sufficiently sharp tool for this purpose, they bite the serpent into pieces with their teeth. Nothing is wasted, for even the back-bone is crushed between the stones and eaten, and the blacks lick and suck the small amount of juice which drops from the meat, and enjoy themselves hugely. But the greatest delicacy is the fat. What cannot be eaten on the spot is put away in the hut, and in this instance they ate the leavings for four whole days, until the meat finally became putrid. When we left the camp I observed that they, strange to say, did not burn these remains of the serpents, which is their usual custom with uneaten food, in order to prevent the witchcraft of strangers.

Snake-flesh has a white colour, and does not look unappetising, but it is dry and almost tasteless. The liver, which I found excellent, tastes remarkably like game, and reminds one of the best parts of the ptarmigan. While they were being carved the serpents diffused an agreeable fragrance like that of fresh beef, and the large liver, which I obtained in exchange for tobacco, supplied me for several days with a welcome change of my monotonous fare.

The natives stand in great fear of poisonous serpents, a fact no doubt due to their helplessness against them. If they discover such a one they usually get out of its way, and if they attempt to kill it they do so by throwing at it from a distance. Accordingly the blacks were frequently surprised to see me go close to a poisonous snake and kill it with a stick. On such occasions they certainly realised the superiority of the white man. For my part, I had gradually become so accustomed to snakes that it simply amused me to see them, if they did not come into too dangerous proximity. The beauty of their forms and motions awakened my admiration, though on the other hand it must be admitted that their life and habits are not particularly interesting.

About two-thirds of the Australian serpents are poisonous, but only five varieties are said to be absolutely dangerous to man.

People who visit the tropics for the first time always fear these reptiles at first, and no doubt justly so, but in course of time they discover that their fear has been too great and that it should be overcome. When a person is bitten it is especially important to keep cool, for fear and excitement make the matter worse and may end in disaster. It is no rare thing for a bushman when bitten to be foolish enough to chop off the bitten limb.

As the serpents are so numerous in Australia, it is of course necessary to keep a sharp look-out and not get too close to them. They may be met with everywhere - on the ground, in the trees, in the water, nay, even in the houses. Though most of the snakes seek their food at night, one's watchfulness should not be relaxed in the daytime. The bushman's precaution of always examining his bed before retiring to rest I deem worthy of imitation. A boy near Rockhampton was bitten by a brown snake in his bed and died.

Deaths from serpent bites are rare in Australia. In a case known to me a man died from the bite of the brown serpent (Diemenia) without feeling any pain to the very last, while I also know of instances where serpent bites have caused the most violent pain.

The serpents are in fact timid, and are inclined to run away from danger, and so far as I have been able to observe, they never attack men unless during the pairing season. But if we come suddenly upon them, their irritable and ugly temper makes them bite with a movement as quick as lightning.

Poisonous serpents were not so numerous here as farther south in Queensland, still they could not be called rare. One day, as we were sitting together round the fire, I was startled by the cry of the blacks, Vindcheh! vindcheh! -that is, Snake! snake! A serpent had appeared in my hut, but hid when it heard the shouting of the blacks. Being utterly unable to get it out of the foliage of which the wall of my hut was constructed, I assumed that it had crept back into the grass which grew outside. The same night I was awakened by some inexplicable cause; there was no sound, and in the clear light of the camp fire no suspicious object could be discerned. At the same moment I discovered a serpent, which was slowly and noiselessly creeping up my left side toward my head. I quietly allowed the snake to proceed until I saw its tail pass my cheek. After a few moments I arose, quickly changed my bed, and slept the rest of the night on the other side of the camp fire. Had I made the slightest motion the snake would doubtless have bitten me.

It was near the end of June. The expeditions I had made during the last weeks were in a certain sense interesting, but they were less profitable than heretofore. I had discovered that there was not much more for me to do here. And even though I might have had a rich field to explore, I was hardly able to stand any longer the many privations and difficulties with which I had to contend.

I did not find my occupation tedious, but still I could not help longing to get away. There was here absolutely nothing of that to which I had been accustomed; for months I had lived with people who were not even able to pronounce my name. A feeling akin to home-sickness kept getting possession of me. I longed for civilisation. No matter how zealous a naturalist a man may be, he is first of all a human being, and when this feeling comes upon us we cannot conquer it, but must perforce give in.

I accordingly went back to Herbert Vale, and prepared to leave these regions and return to Central Queensland.

It was necessary to get some of the natives to go with me to assist in carrying the baggage, but it was important to be careful in the choice of men. I was unwilling to trust myself to the blacks about the station, and the others were afraid of the strange land which we had to traverse. Their speech would betray them, they said, and so they would in a short time be killed and eaten. Yokkai alone expressed a desire to accompany "Mami," still he would not dare unless he was joined by another black man, viz. Chinaman - the person I disliked most of them all. As the reader may remember, he was a great rascal who had caused me much annoyance, but as there was no other way, I had to swallow this bitter pill, for I could not go alone.

With the greatest care all my specimens were packed into large cloths which the postman had brought me from Cardwell, and which I had sewed into a kind of bag. Then all was put on the backs of the horses, and it made them look like camels. Yokkai and Chinaman carried some of the smaller bundles and led the horses, and I followed on foot.

To Yokkai I had given a whole suit of clothes as a reward for his services. I am sorry to say it was about all I was able to do for him. He was, however, exceedingly happy in his first dress and felt more secure against strange blacks, who would judge by his clothes that he was in the service of a white man. The natives hesitate to attack a black man who is dressed, for they are afraid they may be shot by his master. Yokkai had of late talked much about going to Norway - across the great water in the great canoe. There he was sure of getting all he wanted of flour and tobacco. In Norway he would get him a wife, he said. She must be a white woman, but one was enough; it would not be good to have two, he thought. I had also taught him to say Norway, and he believed that we were now bound for that country, with its mountains of "food and tobacco."

On the way my old pack-horse tumbled backwards down a steep river bank, and lay on his side with my valuable baggage under him. I got him up again, and was happy to find that no damage had been done. With the exception of this mishap, I arrived unscathed at Mr. Gardiner's farm at Lower Herbert, where I met with the most friendly reception.

Great changes had been made here since I left. I could scarcely recognise the place. Near the farm a whole sugar plantation had grown up. Where the dense scrubs flourished when I was there before, the fields were now covered with sugar-cane, and there was life and bustle everywhere. On the plantation I got some boxes, in which I packed my collection, and soon was ready to go on board a barge which was to carry me down the river to Dungeness.

Yokkai took a deep interest in all that he saw and heard. He lived high, stuffed himself with sugar-cane, and pretended to be a man of great importance; in this case it certainly was "the clothes that made the man." But everything was so new and strange to him that he did not feel perfectly at home. He had already given up the journey across the great water, and he was longing to get back to his own mountains.

I had taken precautions that he should in no way suffer in "the strange land," and I also made arrangements for his safe return to his own tribe.

Before I went on board the boat I asked him if he would like to go with me to Norway. He shrugged his shoulders and answered a positive No. I shook his hand and bade him good-bye; but I did not discover the faintest sign of emotion. He gazed at me steadfastly with his large brown eyes beneath his broad-brimmed hat, but did not understand the significance of shaking hands. Thus I parted from my only friend among the savages, and many emotions crowded upon me as the vessel glided away, memories of the stirring days I had passed with him, and a sense of deep gratitude for the many services he had done me.

Upon the whole, I took leave of the country of the blacks and my interesting life in the mountains with strange feelings in my breast. Some of the impressions derived from this grand phase of nature I shall never forget. When the tropical sun with its bright dazzling rays rises in the early morning above the dewy trees of the scrub, when the Australian bird of paradise arranges its magnificent plumage in the first sunbeams, and when all nature awakens to a new life which can be conceived but cannot be described, it makes one sorry to be alone to admire all this beauty. Or when the full moon throws her pale light over the scrub-clad tops of the mountains and over the vast plains below, while the breezes play gently with the leaves of the palm-tree, and when the mystic voices of the night birds ring out on the still quiet night, there is indeed melancholy, but also untold beauty, in such a situation.

I was, however, not sorry to leave the people. I had come to Herbert Vale full of sympathy for this race, which the settler drives before him with the rifle, but after the long months I had spent with them my sympathy was gone and only my interest in them remained. Experience had taught me that it is not only among civilised people that men are not so good as they ought to be.