Wild landscape on the Upper Herbert - Kvingan, the devil of the blacks - A fatal eel - Mourning dress - Flight of the blacks - A compromise - Christmas Eve - Lonely - Christmas fare - A "faithful" relative - A welcome wallaby.

The season was already so far advanced that it was out of the question to get back to my headquarters before Christmas. The new "land," which we reached after a short time, presented a grand, wild, and romantic aspect. We descended from the tableland and suddenly got sight of Herbert River, flowing dark and restless far down in the depths below.

We followed the bend of the river to the east, walking on a ledge of the steep mountain nearly a thousand feet above the level of the water. Below us the mountain presented a wild, broken mass, while above it was overgrown with dense scrubs. Near the chief bend of the river we made our camp by the side of a mountain brook which plunged down over the precipice. It was no easy matter to find a place for a camp here, for it was a spot on which a person could scarcely lie in a horizontal position.

The natives had some strange superstitions in regard to this place. In the depths below dwelt a monster, Yamina, which ate men, and of which the natives stood in mortal fear. No one dared to sleep down there. Blacks who had attempted to do so had been eaten, and once, when a dance had been held there, some persons had been lost. I proposed to take a walk thither, but they simply shrugged their shoulders and did not answer. A gun would be of no use they said, for the monster was invulnerable.

It was Kvingan, their evil spirit, who chiefly haunted this spot His voice was often heard of an evening or at night from the abyss or from the scrubs, I made the discovery that the strange melancholy voice which they attributed to the spirit belonged to a bird which could be heard at a very great distance. But I must admit that it is the most mysterious bird's voice that I have ever heard, and it is not strange that a people so savage as the Australian natives should have formed superstitious notions in regard to it. Kvingan is found in the most inaccessible mountain regions, and I have heard it not only here but also in the adjoining districts. During these moonlight nights I tried several times to induce the natives to go with me to shoot the bird, but it was, of course, blasphemous to propose such a thing, and their consent was out of the question.

At other times, when they spoke of their evil spirit, I found that it manifested itself in a cicada. Their notions in regard to their evil spirit appeared to be very much confused. This insect, the cicada, produces in the summer a very shrill sound in the tree-tops, but it is impossible to discover it by the sound. It is this loud shrill sound, which comes from every direction, and which is not to be traced to any particular place, that has evidently given rise to superstitious ideas concerning it.

In the south-eastern part of Australia the evil spirit of the natives is called Bunjup [Bunyip], a monster which is believed to dwell in the lakes. It has of late been supposed that this is a mammal of considerable size that has not yet been discovered. It may be added that the devil in various parts of Australia is described as a monster with countless eyes and ears, so that he is able to see and hear in all directions. He has sharp claws, and can run so fast that it is difficult to escape him. He is cruel, and spares no one either young or old. The reason that the natives so frequently move their camp is, no doubt, owing to the fact that they are anxious to avoid the devil, who constantly discovers where they are. At times he is supposed to reveal himself to the older and more experienced men in the tribe, who accordingly are highly esteemed. The natives on the Gulf of Carpentaria say that the devil's lips are fastened by a string to his forehead.

With the exception of the instance already described I never heard of any effort being made by the natives to propitiate the wrath of this evil being. They simply have a superstitious fear of it and of the unknown generally.

We searched the scrubs in the vicinity thoroughly, and found many traces of boongary in the trees, but they were all old. The animal had been exterminated by the natives. It could be hunted more easily here, for the reason that the lawyer-palm is rare, and consequently the woods are less dense. The natives told me that their old men in former times had killed many boongary in these woods on the tableland.

Two of my men brought to the camp a very large eel, about as thick as a man's arm and very long. They had found it dead, for the sun had dried up the puddle in which it had lived. This was enough to keep me from tasting it; but the blacks were very much excited about it. It was prepared in the same refined manner as the chief delicacies of the natives.

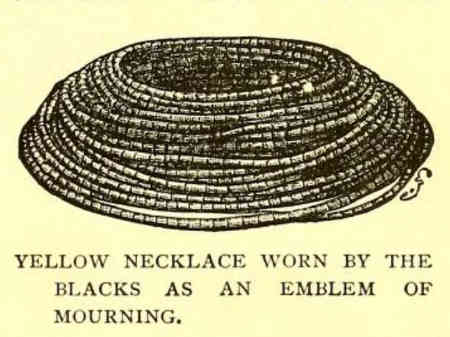

Several of my companions were not old enough to be permitted to enjoy the privilege of tasting it. Others wearing yellow necklaces as an emblem of sorrow were also forbidden to eat of this aristocratic food. These necklaces consist, as above stated, of short-cut pieces of yellow grass strung on a string long enough to go round the neck ten to twelve times. Sometimes they are worn as ornaments by both men and women. While in mourning the Australian natives carefully abstain from certain kinds of food, and it was a surprise to me that they could maintain this fast so well as they did; but at last I found out that the reason for this was a superstitious notion that the forbidden food, if eaten, would burn up their bowels. They are very happy when the season of mourning is ended, and although they have but vague notions of time, they know precisely when they may lay aside their mourning dress - that is, the yellow necklace.

I have also seen the women paint their bodies with chalk while they are in mourning. Near Rockhampton the blacks used to cut themselves with stones or tomahawks; the women besides paint round their eyes with white chalk. On the Barcoo I once met two women who had their whole head plastered over with the same kind of stuff, which they wear for weeks.

Their sorrow for the dead is not very deep; they chant their funeral dirge for several evenings, but this is simply a formal respect paid the deceased, I have many times heard these melancholy mourning tunes in the silent night. The same strophe - for example, Wainta, bemo, bemo, yongool naiko? (Where is my brother's son, the only one I had?) - was continually repeated. As a rule, the old women furnished the lamentations.

In the vicinity of Coomooboolaroo in Central Queensland an old woman exhibited her sorrow at the deathbed of her husband in a very singular manner. Having made a series of breakneck somersaults along the ground, she took two pieces of wood and beat them together in despair. Her husband died soon afterwards, and in a quarter of an hour he was buried.

During the days of mourning the deceased is rarely mentioned, and when the yellow necklace has been laid aside his name is never heard again. This is doubtless the reason why the Australian natives have no traditions. Many of them do not even know their father, and any knowledge of earlier generations is out of the question. Strange thoughts came to my mind as I walked the scrub paths which the blacks had trodden with their naked feet for centuries. Here generation had succeeded generation without a thought in regard to the past, and with no care in reference to the future, living only for the present moment.

In the evening, after the eel had been consumed, the natives laid themselves round the fire and enjoyed rest after the toils of the day. It was late, and I thought my men were sleeping. The beaming rays of the full moon illuminated the romantic landscape. Now and then the silence was broken by the mysterious notes of that singular night bird, the evil spirit of the natives. Suddenly two of the natives arose, came to my hut, and said: "We must depart, a great water will rise here; this is not a good place to remain in!"

I remained perfectly calm and quiet in my hut, and expressed my contempt for their silly notions. I answered that they might go if they pleased, but that I would stay where I was. My opinion was that they would remain with me. But presently they all got up, and pointing with their open hands to the two persons who had eaten the eel, they said that these men best understood the dangers connected with this place.

The fact was, of course, that they had become ill from eating the eel, which had died a natural death. They now cursed the place by spitting in all directions. The others followed their example, and immediately thereupon they all proceeded up the mountain slope, spitting all the time. I hoped they would return, but in this I was disappointed.

At length I came to the conclusion that it would be best for me to follow them, lest they should leave me altogether. In that case my situation would be a most deplorable one; for, although I had abundance of tobacco, my supply of provisions was very low, and without the aid of the natives I would be unable to get the necessaries of life. Game is scarce in this part of the world, and the vegetables are either uneatable or of very poor quality. All I had in my possession was a small piece of meat and a handful or two of flour, scarcely enough for a small damper.

I arose and climbed after them up a grassy and stony slope extending to the top of the mountain along the scrub. The moon shone bright and clear, so that it was not difficult to find the path. I called to them, but they did not answer. Finally I reached the summit, and there I caught sight of them. They sat crouched together under a casuarina tree, and were utterly speechless. They had actually intended to run away. But when they heard me calling they decided to wait, in order that I might join them and go to the "land" we had left. This place was evidently too full of Kvingan.

I refused, however, to go, and threatened to return to Herbert Vale and get the black police to deal with the matter, and they, I said, would hunt them for months and shoot them. On the other hand, I used kind words and promised them much tobacco, the only thing I had left worth mentioning. Without guides I could not, of course, continue my journey. We finally compromised the matter. I agreed that we should all sleep on the summit of the mountain, but, on the other hand, they were to go with me down to the camp to fetch our baggage. Strange to say, they made no objections to this proposition. Their main object was to avoid sleeping down in the valley.

On our return to the camp we found that the dingo had availed himself of the opportunity of stealing the small piece of meat I had left. All agreed that he should suffer for this mischief, but unfortunately he was nowhere to be found.

The next day we came into a wild region abounding in scrubs and declivities. Progress was most difficult, and it was almost impossible to find a place suitable for a camp. Otero, who knew the country, conducted us at last to a small flat spot near the upper edge of the scrub. Here there was a little brook, though, upon the whole, water was very scarce in this region. We remained here several days. I had never before seen so many fresh traces of boongary, and the natives did their best to secure specimens of the animal in this terrible locality; but we had no dog, for the tribes we had visited had none, and the want of dogs was a great misfortune. Still we were not discouraged. It must, however, be admitted that the blacks did not feel perfectly safe in this region: mal was not very far away. We could see smoke on the mountains very distinctly, when they burned the grass to hunt the wallaby.

One day, as we were rambling through the scrubs, we heard somebody chopping with an axe in the distance. Otero climbed a tree in order to give a signal to the persons chopping, for he was acquainted with the tribe that owned this "land." He shouted at the top of his voice, the chopping ceased, and a shout was heard from the distance.

Otero shouted: Ngipa ngipa Ka-au-ri! - that is, I - I [am] Ka-au-ri !

My blacks had already comprehended the situation. The man whom we had heard chopping was out in search of honey, and from this they at once made up their minds as to where his camp was, for the natives usually have regular places for camping. They also discovered his name, for they knew whose land it was. Where the women of the tribe were, and what they were doing, my men also seemed to know; for it was the season for harvesting a certain kind of fruit, and they knew where this fruit grew most abundantly.

In other parts of Australia I have seen the people make signals with fires, indicating by the number of columns of smoke in what direction they intended to go, etcetera. It is said that they can also make themselves understood by the inflection of the words shouted.

It was Christmas Eve, and in honour of the day I had requested my men to do their best to procure me something good to eat. I had promised them twice the usual amount of tobacco if they were successful.

I was sitting all alone by my hut. A strange feeling came over me as I pondered on the fact that it was Christmas Eve, and that I was in the midst of an Australian forest and far away from the borders of civilisation. The summer sun had clad the neighbouring hills with a heavy carpet of green, the gloomy scrubs below had the appearance of a boundless sea, and the sun shone in all its effulgence on the fresh colours. On the summit of the mountain where I was sitting it was somewhat cooler than in the bottom of the valley, where the heat was oppressive. There was not a breath of air stirring, and the entire landscape presented a scene of refreshing repose. In the tree-tops the cicadas vociferously chanted the praises of the midsummer. All was light and cheerful, - if we had only had something to eat!

All I had was a piece of bread; rather slender fare for Christmas. In the afternoon the natives returned, bringing a few pieces of a rare root called vondo, some honey, and a few white larvae. But the nicest present they brought me was an animal, which I had not seen before. The natives called it borrogo. It is a marsupial of a brownish-yellow colour, and about the size of a small cat. My menu therefore was: broiled borrogo, a small piece of bread, broiled vondo and honey mixed with water.

The food was not to be complained of, the only trouble being that there was not enough for so many people as we were. I could not help thinking of all the kettles in which delicious rice porridge was now boiling in far-off Norway. What would I not have given for a plate of it!

Thus it will be seen that it is no easy matter to sustain life in the wilds of North Australia, when one has to depend upon what he can find in the woods and on the plains. The fare of the Australian native is not well adapted to the wants of the constitution of a European. The flesh of the marsupials has a sickly taste, while talegallas and pigeons, the best game to be had, are rare. Lizards are not bad, but snakes are dry and tasteless. There are only one or two kinds of fruits or roots that can be eaten with appetite. One of them is the above-mentioned vondo, which grows in sandy soil on the summit of the scrub-clad mountains, has a stem as slender as a thread, and climbs the trees; hence is difficult for any one but a native to find it. A fig called yanki which is yellowish in colour and semi-transparent, has an excellent flavour, but it is so rare that I did not see it more than a single time during my whole sojourn in Northern Queensland. Another variety of fig, veera, grows on the grassy plains and is more common.

One evening a dingo came stealing into the camp, and we soon discovered that it was our old runaway rogue who had abused our hospitality in so shameful a manner. The natives eagerly besought me to shoot it, and although I had a faint hope that it might be of some use to me, I finally yielded to their entreaties, and to their great satisfaction made the dingo suffer the penalty of death.

On our march through the scrub I heard Otero tell one of his comrades, that in that very place he had once seen a boongary jump from a tree down on the ground and then disappear. He pointed out the tree. This report made me still more eager, but all our exertions were in vain. Meanwhile we secured a few other specimens of Australian fauna, and among them four little flying-squirrels (Petaurus breviceps), which we found lying together in a hollow tree.

It was still very difficult to secure a sufficient amount of food; and when Otero one day suddenly absconded, remaining longer was out of the question, for the others were all strangers in this "land," and hence they felt unsafe and were anxious to get home.

The one who, next after me, had the most cause to be vexed at Otero's flight was Yanki, his faithful relative. Yanki had on all occasions devoted himself to his Otero - had shared with him his food, his tobacco, and all other good things he had. Despite his innocent looks, Otero had now run away, and he had also taken Yanki's shirt with him. His conduct was most disgraceful, and it illustrates how little the Australian blacks are to be depended on.

I persuaded the others to remain here one day longer, and promised them to shoot a wallaby when we reached the grassy plain. But they were of but little service to me after we had lost our guide, and we were obliged to leave, to get something to eat, if for no other reason.

We had to take a zigzag course to reach the bottom of Herbert River valley, so steep was the descent. A rock-wallaby ran across our path and disappeared at once. At noon we passed the great falls of the river, and made a short halt in their vicinity. The surroundings were exceedingly wild and romantic, but I confess I was too hungry to enjoy the imposing scenery. Then we followed the course of the river, and walked as fast as we were able in the high grass. All nature seemed to be fast asleep. We did not see a sign of life as we walked along the bank of the river in the scorching heat of the sun and in the tall grass. The only sound I heard was the roar of the waterfall thundering among the mountains in the distance. It has been said that an Australian landscape breathes melancholy, and the truth of this statement is fully appreciated by a person who, on a day like this, wanders amid these sober, awe-inspiring gum trees and acacias. One's mind cannot help being overcome by a sense of solitude and desertion.

One or two hours before sunset and early in the morning the wallabies are in the habit of coming out to feed on the grass, and at such times it is not very difficult to get within shooting range of them; but on this particular evening they were very shy. The few that we got sight of disappeared again, thus frustrating all hopes of getting a good supper that night.

It was late and perfectly dark when we arrived at our old camp, where we had left our horses. I had been prudent enough to save a small piece of bread for myself, and I would have preferred as usual to share it with my men, but it was not enough to divide, and besides, I knew that the natives were able to endure hunger far better than I was.

As they had nothing to eat, I gave them a little tobacco, in order that they might have some comfort; but they put it away without smoking it, and soon laid themselves down by the fire to sleep the time away - a common habit of the blacks when it, for instance in the wet season, is difficult to secure food to allay their hunger.

We had left the horses in a place enclosed by nature in such a manner that they could not get away. It would, therefore, be an easy matter to find them, provided they had not been killed by the natives during our long absence. There was reason to suspect this, and we were agreeably surprised when, in the darkness of the night, we heard the tinkling of the bell, and the next morning found them all safe and sound.

Before sunrise the next morning Ganindali and I set out to hunt the wallaby, and near the camp we discovered a large number feeding on the grass, and shot two of them. Ganindali brought one to the camp, and asked one of his comrades to fetch the other, while he and the rest began to cook the first. This produced life in the camp! Within two minutes a splendid fire was burning. One of the animals was thrown upon the burning embers, and was turned by its long tail. Ganindali acted as chief cook. When the. hair was scorched off the skin, the animal was dragged out of the fire. The belly was opened with a sharp stone, and the entrails were drawn out. Four red-hot stones replaced the bowels, and the animal was placed on the cinders. As soon as it was tolerably well roasted, the blacks attacked it most greedily and tore it into pieces.

Before long they had eaten their fill of the juicy meat; then they ran down to the river, waded a little way into the stream, and drank from the hollow of their hands. Having quenched their thirst, they returned in a leisurely way to the camp and resumed their eating. Then they sat down round the fire and began lighting their pipes. But they did not want to light their pipes with embers from the fire; they demanded matches. I did not as a rule give them matches when we sat round a blazing fire, but now, as our journey was nearly at an end, I did not begrudge them the pleasure of lighting their pipes in the same manner as the white man does, and of hearing the crack of a match. Meanwhile I, too, had finished my supper, and the unsavoury kangaroo flesh had a most excellent flavour on this occasion.