Blacks on the track - A foreign tribe - Native baskets - Two black boys - Bringing up of the children - Pseudochirus lemuroides with its young - The effect of a shot - A native swell - Relationship among the blacks - Their old women.

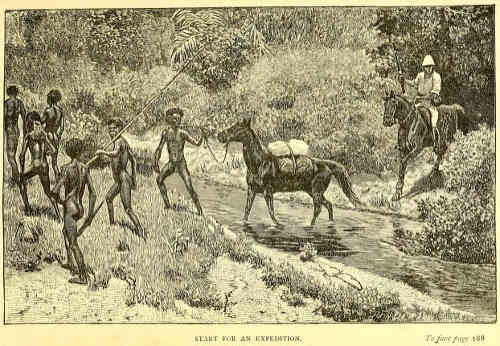

It was more difficult than ever to secure men. The country we were to visit was situated so far away that the blacks I approached made all sorts of objections. They did not care to run the risk of being eaten. My friends also advised me most positively not to undertake the expedition. Both Willy and Jacky shook their heads, saying, Komorbory talgoro - that is, Much human flesh. The people there were all myall, they said, and would eat both us and our horses, but I comforted myself with the fact that I had in my company a man who belonged to a family tribe living near the boundary of the land we were to visit. Ganindali was also acquainted with one of the neighbouring tribes. Besides, I had with me a "civilised" black, on whom I could place considerable reliance.

On leaving Herbert Vale in the morning the old women took leave of us in a horrible manner, crying and groaning because their friends were going to a dangerous land; there is, however, an old saying that you must not take evil omens from old women.

We followed Herbert river in a north-western direction, and at noon rested on the river bank. Just as we were ready to continue our journey, we were overtaken by a violent thunder-storm. Before the rainy season begins thunder-showers are frequent, and come on very suddenly, sometimes attended by terrific winds. Flashes of lightning and peals of thunder came almost simultaneously. My men at once sought shelter under the trees, and they could not comprehend why I stood in the open field and got wet. Strange to say, the natives have no fear of thunder and lightning, which they say are very angry with the trees but do not kill the blacks. Though many trees are seen splintered by lightning, they do not understand that it is dangerous for them to seek shelter under them in a thunder-storm.

We went up along the river as far as it was possible to ride, and crossed it three times. In some places it was a raging torrent, while in others it flowed quietly, but the large stones on the bottom always made the crossing difficult, and twice I had to unload the baggage and let the natives carry it. For the sake of convenience I was lightly clad, wearing simply a shirt, shoes, and round my waist a belt in which I carried my revolver. I also tried to go barefooted like the natives, but I had to give it up, for the stones, heated by the sun, burned my feet. Sometimes the river formed large basins, in which the water was deep, dark, and still, as in a pond. These the crocodiles like to frequent.

The farther we ascended the narrower the valley became, and at last it was impassable for horses. So we made a camp, where we left the horses, distributing the baggage among the natives. Our aim now was to find a little tribe with which Ganindali was acquainted, and which I hoped would be of service to us in hunting the boongary.

I observed with interest how my men acted in order to discover these people. They sought out every trace to be found, took notice of broken branches and bark, or of stones that were turned, or of a little moss that had been rubbed off; in short, of everything that would escape a white man's attention, and which he hardly would understand if his attention were drawn to it.

The keen ability of the Australian to find and follow traces seems to be unique, and doubtless surpasses even that of the North American Indians. The white population has been greatly benefited by this sleuth-hound talent of theirs, which has rendered valuable service in the discovery of murderers. A black tracker of the native police can pursue a trace at full gallop.

The first day we did not succeed in finding the above tribe, but we saw several of their deserted camps. The natives do not destroy their primitive huts when they change their abode, but outside the camp they leave a palm leaf to indicate to their friends in what direction they have gone. By the aid of these signals we finally got on the sure track of the strange tribe. At one of these camps we also found a dingo that had run away from its owner. As it might prove useful to us, we fed it, and thus persuaded it to go with us.

Not until the afternoon of the third day did we approach the little tribe. The natives showed me smoke not far away. As usual, I sent a couple of men in advance to announce our arrival. The strangers were reserved and silent, as they usually are the first time they come in contact with the white man. Some tribes are less cautious on such occasions, and they are in the habit of feeling him all over his body to assure themselves that he is a human being.

On entering the camp I noticed a few women, who sat beating fruits, while two or three of the older men were busy plaiting baskets. The young men were lying down doing nothing.

As soon as the natives became acquainted with my purpose, they were so polite that they sent a message to an old man who lived in the neighbourhood, and had the reputation of being a most skilful boongary hunter. We had to wait for the old man about a day, and this time I spent in the camp with these children of nature. Here they lived uninfluenced by any form of civilisation, uncontaminated by the corruption which always manifests itself when the natives have had intercourse with white men. It was nature in her pristine state, and it is this kind of savage which it is most profitable to study. Nor are these blacks as dangerous as those who have become familiar with the white man's customs and character.

The men sleep late in the morning, for they do not care to go out before ten or eleven o'clock, when the dew has left the grass. The first task of the women in the morning is to kindle a fire, which is always built at the entrance to the hut, where the family gradually assemble. They seat themselves in the ashes, stretch themselves a long time, and spend half an hour in scraping and scratching their bodies, a favourite occupation when they sit round the fire. When the men are thoroughly awake they reach out for the baskets, which are filled with tobola, kadjera, or perchance with the remnants of a roasted wallaby. What the blacks are unable to eat on the spot is put away, and may be kept for one or two days. Meat is slightly roasted for this purpose, or it may be preserved in water. Then the women and the children go out to gather fruits, while the men proceed on some hunting expedition or to look for honey. Every day, when it does not rain, the Australian must have his hunt; even the natives who are sufficiently civilised to be employed in the native police force feel this necessity so strongly that they occasionally take off their clothes and make an expedition with the tomahawk. When they return in the afternoon the inevitable fires are at once built; some of them lie down to sleep, while others chat a little and wait for the women to come back with fruits. Some one of the old men may go to work at a basket on which he is engaged.

The women come home late in the afternoon, and then have their hands full preparing the poisonous plants, but they never work late in the evening. If they have brought much they leave it until the next day. All now enjoy a dolce far niente after the more or less fatiguing work of the day. There is nothing to tax their brains, and they have no cares. They have no concern about the morrow or for the future in general. But few words are spoken. They feel somewhat anxious for their lives when night drops her curtain upon the camp, but gradually the whole family falls asleep, and nothing is heard save the melancholy buzzing of insects in the profound silence of the scrubs.

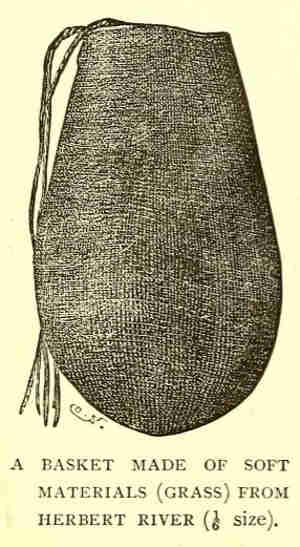

A little before sundown the next day the old man arrived, accompanied by his two good-looking, well-fed wives. He was one of the oldest men in the tribe and was highly respected. As soon as they entered the camp they seated themselves with crossed legs, but said nothing. When they had rested a while the old man ordered out his wives to find palm leaves for a hut, which was built in a few minutes. To show us that we were welcome, they sent a present, consisting of two large baskets, to our camp, which we had made close by. It was an act of politeness which my blacks expected, and had mentioned to me in advance. The baskets were very nice, in fact admirable specimens of native handiwork

In this strange tribe there were two little boys who pleased me particularly. They took a deep interest in me and my camp, and they were not afraid to approach me. They were also very accommodating. I was astonished to find them so obliging and kind, but I have since seen other instances of a similar kind. The black children are not, upon the whole, as bad as one might suppose, considering their education, in which their wills are never resisted. The mother is always fond of her child, and I have often admired her patience with it. She constantly carries it with her at first in a basket, but later on, when it is big enough, on her shoulders, where either she supports it with her hand or else the child holds itself fast by its mother's head. Thus she carries it with her till it is several years old. If the child cries she may perhaps get angry, but she will never allow herself to strike it. The children are never chastised either by the father or the mother.

An acquaintance of mine, who had associated extensively with the blacks, once gave a naughty child a box on the ear, at which the mother became very much excited, and said, "There was no use in striking the child. He was only a little fellow, not big enough."

Before the children are big enough to hold a pipe in their mouth they are permitted to smoke, and the mother will share her pipe with the nursing babe.

The children always belong to the tribe of their father, but are fonder of their mother than of their father. When grown up they rarely mention him, in fact often-times do not know who he is; for the women frequently change husbands. The father may also be good to the child, and he frequently carries it, takes it in his lap, pats it, searches its hair, plays with it, and makes little boomerangs which he teaches it to throw. He however, prefers boys to girls, and does not pay much attention to the latter. The children play all day long, build mounds, draw figures in the sand, throw boomerangs, etcetera.

Thus they grow up in perfect freedom, and are never punished. As soon as they can walk they acquire the manners and habits of their elders, but the boys are not permitted to go hunting with their fathers before they are nine years old. Little boys are treated like grown men, or to speak more correctly, the Australian never becomes a man, the father being in thought and deed as much a child as the son.

When the men are in camp their chief occupation, providing they do not sleep, is to make weapons, and particularly to plait baskets. It was interesting to observe their marvellous skill in this work. Only the men plait baskets - the women never - and they are proud of exhibiting the most beautiful specimens of their handiwork.

The basket varies in size, but the shape is usually the same, more or less oval, narrow at the top and broad at the bottom. The material consists almost exclusively of the branches of the lawyer-palm, which are split with the aid of the teeth into thin slender strings, and these are scraped smooth and even with clam-shells and stones. The baskets are made wonderfully fine and strong, and are often painted with red, yellow, or white ochre, and sometimes with stripes or dots of human blood, which the maker takes from his own arm. The basket is carried by a handle made of the same material, and hangs down the back. The handle is placed against the forehead, so that the weight of the basket rests on the head of the person carrying it, as the blacks do not like to carry anything in their hands.

We arose early in the morning to hunt the boongary; for we had a long day's march before us to the place where this animal was said to be found in great numbers. I did not expect anybody but the old man and one or two of the blacks to accompany me, but we were joined by the whole tribe, so that we were a large party as we proceeded across the tableland. At noon we discovered in the distance a series of scrub-clad hills rising one above the other, and these we were to reach in the evening. The men and I then took a circuitous route through a scrub, while the women, carrying the provisions and the men's weapons, went directly to the place where we were to pitch our camp for the night. On their journeys the natives seldom carry their provisions with them, but depend for their subsistence on what they can find on the way. They therefore take different routes, not very wide apart, and assemble in the evening in the place agreed upon for a camp, bringing with them the opossums, lizards, eggs, honey, and whatever else they may have collected during the day.

The only result of our march was a considerable amount of honey, which we found near the top of a high tree, which from its character the natives believed to be hollow all the way down to the root. The honey would in that case have fallen to the bottom and been wasted if they had attempted to gather it in the usual way - by cutting a hole in the trunk. They therefore borrowed my axe to fell the large tree, which was more than three feet in diameter, and of very hard wood. They worked very industriously for an hour and a half, taking turns at chopping down the gigantic tree, and they did not rest till it fell. This may serve as an illustration of the perseverance and energy of the otherwise indolent and lazy Australian native while pursuing any game that he has discovered.

They were well rewarded for their trouble. The great amount of honey found in this tree astonished me, and it had a fine flavour and in spite of the excessive heat was solid and cool. The natives brought the greater part of the honey to a brook close by, and not having any trough at hand, they mixed the old and the new honey with water in the most primitive manner. They laid the honey in a hollow rock near the stream, and scooped water into it with both hands, afterwards stirring it. Then they all sat down round the "flowing bowl," and with tufts of fine grass, growing near, they soon emptied the hollow rock.

Upon our arrival at the camp the women were sitting on the green grass round a little fire. A strange tribe had come to the camp, who were friendly to my companions. All were as lazy as possible; some lying on their backs, others sitting still and gazing vacantly into space, while a few were engaged in conversation. The women had told the strange tribe about the arrival of the white man, and had of course made great boasts of the tobacco and provisions which he carried with him. They were very proud of having him with their own tribe, but had not made the slightest preparations for building huts nor even gathered palm leaves. As soon as we came the women began to bestir themselves, for the sun was already setting. The strange tribe, and many of those who had come with me, encamped on the one side of the valley, while my men and I pitched our camp on the other side.

It was an excellent locality for hunting the boongary, and not so difficult to penetrate as the scrubs in the mountains. Our semi-wild dingo was utterly useless, and I had no person with me whom it would follow; but I was now accompanied by so large a number of natives that I still looked for good results.

In the scrubs here I shot a very remarkable specimen of a phalanger, which has since been described by the name of Pseudochirus lemuroides, because it bears a certain resemblance to the lemurs of Madagascar; its tail is not smooth on the under side, as in the other members of this family, but is nearly entirely covered with hair. In some respects it unites the characteristics of the phalanger proper with the pseudochirus, and thus possibly forms a new sub-genus, Hemibelideus. The natives call it yabby. They first attempted to kill it in the usual way - by climbing the trees and throwing sticks at it. The animal is not very shy, but when disturbed it runs rapidly out upon the branches, so that it is difficult for a native to kill it unless he has one or two of his companions to hinder it escaping on to the neighbouring trees. The natives kill all phalangers in this manner. In order to end the chase the natives shouted to me and asked me to shoot it. It fell from the branch, but remained for a moment suspended by the tail before it dropped down dead. When they saw the animal fall from so great a height they broke out in shouts of wonderment, and this event was for a long time the leading subject of conversation among them. It proved to be a female with a remarkably large young one, entirely covered with hair, in her pouch. The young one, which had also received a fatal shot, was nearly half the size of its mother. Although it was midsummer, the animal had a full coat of hair on its beautiful skin. I have found no marsupials of this kind since, and the two above described are the only specimens that have hitherto been shot. The Pseudochirus lemuroides is not found in the part of the Coast Mountains lying east of Gowri Creek. We first meet with it in the mountains between Gowri Creek and Herbert River, and it increases in number as we proceed toward the north; these two specimens were shot in a tableland scrub.

Late one evening, after we, as usual, had encamped on both sides of the little valley which extended down toward the river, a shout came from the other camp that hostile natives were heard in the grass on the other side of the river from where our camp was situated. My companions arose at once and cried Kolle! mal! - that is, Hush! man!

I was so accustomed to the imaginary fears of the natives in the evening that I did not pay much attention to their alarm, but a few moments later I too thought I heard voices in the distance. No sooner had my men discovered my suspicion than they called over to the other camp, "Mami1 also hears. "There was now a stillness so profound that a leaf falling to the ground might have been heard. For my part I attributed the suspicious sound to the trees rubbing against each other in the evening breeze. My opinion was at once reported to the other camp; but the natives there were not to be quieted; they still heard voices, and after a short time a number of young men, followed by children crying with all their might, came to me: all were very much frightened. I was obliged to rise and fire two shots in the pitchy darkness of the night; this quieted my men, and they even expressed their sympathy for their comrades in the other camp, where there reigned the stillness of death, and where an old man stood guard during the whole night. From what I afterwards learned I am persuaded that we had actually heard the voices of a hostile tribe, which in all probability would have attacked us had I not frightened them away with my shooting. How little it takes to demonstrate the superiority of a civilised man over the savage!

1 Mami, which means a great man, is the same name as the natives give to / the officers of the native police. Thus they gave me the highest title of which I they had any knowledge.

I found it useless to remain here any longer. There were but few traces of boongary to be seen, and the natives had, during the whole time, evinced little disposition to hunt them, partly because the animals were so scarce, and partly because we did not have dogs. My men, however, had much to say of a more distant "land," where they claimed there were komorbory (many) boongary. They were, however, afraid to accompany me thither, on account of strange tribes. Nevertheless I determined to visit this "land," but as not one of my people would admit that he was acquainted with it, I had to try to find a guide among natives who had friends there. This proved to be a far more difficult task than I had supposed. I offered provisions, I offered tobacco - but all in vain. All thought it was sheer madness to attempt to go there, for they were afraid of the strangers whom they had heard that night.

I tried to make a friend of the old boongary hunter, and gave him something to eat. Before meeting me he had tasted neither salt beef nor damper, and he had become exceedingly fond of both. He ate with a ravenous appetite, but stubbornly refused to accede to my wishes. After much parleying I at length succeeded in inducing one of them to go with me by giving him a shirt and the promise of much tobacco and much food if he procured a boongary. To make sure of him I gave the old hunter, who had considerable influence over him, a large piece of meat, and requested him to encourage my new guide to stand by his purpose and go with me.

The old man kept but a very small piece for himself, and with the liberality peculiar to the Australian native, generously distributed the rest in all directions for the purpose of enhancing his influence in the tribe. The Australian native is by nature lavish, and when he bestows gifts he does it liberally. Thus when a civilised black man returns with his master to the station after a prolonged journey he shows great liberality to his comrades, who then gather round him. His new clothes are freely distributed, and after a few hours one black may be seen wearing his trousers, another his spurs, a third his hat, etcetera, while he himself frequently retains nothing but the shirt.

The black man whom I had persuaded to go with me was related to one of my men, Yanki. He was Yanki's Otero In the tribes the words otero, gorgero, gorilla, and gorgorilla are found, which designate various kinds of relations. Sometimes a man would be called otero or gojgero without the addition of any other name, and still everybody knew who was meant. There are similar words to designate female relatives, in which case the termination 'ingan' is substituted for the final or a, thus oteringan, gorgeringan, etcetera.

Doubtless these appellations are in some way connected with the matrimonial system of the natives, but I have never been able to get to the bottom of this subject. The natives were either unwilling or unable to give me a satisfactory explanation, while the men, contrary to what has been experienced in other places, made no objections to telling me their own or the women's names, or who was their otero, etcetera. As a rule the members of Australian communities are divided into four classes, and according to the Australian author Mr. E. M. Curr, the object of this division is to prevent the intermarriage of relatives, a thing for which the Australian natives appear to have the greatest abhorrence.

Yanki was exceedingly amiable to his otero, and was very happy that he was to be one of my party. Yanki was to share his bed and his tobacco with him, and they were to have a very nice time together. And now the rest of my men were willing to accompany me. Happy at the result, I gave small pieces of meat to those who were not going with me, and we parted the best of friends.

It did not escape my observation that during all these negotiations the blacks kept consulting an old woman. She took a very serious part in the discussion, and gave the most positive advice not to accompany me because mal had been so near to us that night. The reason why the natives consulted her I do not know. It may be that she was skilful in procuring human flesh and other food. The Australian native has a certain respect for old women, provided the latter are not too old to be useful. The instinct of the blacks for finding food seems to increase with their years, the fact being, I suppose, that they have the advantage of experience. Old women usually take part in the hunting of human game, and they even find means of supporting those of their sex who are too old to leave the camp and seek food for themselves. Were this not the case the men would certainly soon get these old women out of the way; for the Australian does not hesitate to remove anything which is an obstacle to him. But these old women are far from being superfluous. I have often seen strong young men appeal to them for food, and their requests have been granted.

As we were proceeding across the grassy plain my men suddenly shouted, Boongary! boongary! and started off after an animal which disappeared behind a grassy hill. They soon returned with empty hands, but they were convinced that they had seen a boongary. I expressed my surprise at its being found on the grassy plain; but the natives assured me that it moved about a great deal, and made long journeys across the tableland from one scrub to the other.