- Atherton Tablelands

In 1893, historian Frederick Jackson Turner reported that the American frontier had ended. The wild had been tamed and the west was won. In North Queensland, Australia, a new frontier had just begun.

In 1893 the cobb & co coach rattled through the new pioneering settlements of Watsonville and Bakerville. The timber and corrugated iron architecture and many canvas camps had an air of impermanency. But who knew where a humble camp would turn into a thriving city or major provincial town? On the frontier anything could happen. The answer lay hidden in the ground and men dug for it from dawn till dusk. They drank their sorrows away afterwards, or rejoiced by filling wash-tubs with champagne and ladling it out for all and sundry.

When the passengers spilled out of the coach at Irvinebank they were greeted with the smell of freshly sawn timber and the manure and debris of mule teams, bullock teams, pack horses and donkeys.

Men trod in to the town on hobnailed boots pushing wheelbarrows containing all of their worldly possessions and families arrived by the cartload for the Vulcan Mine was proving a rich and stable source of tin. The mill built by John Moffat & co gave forth the steady sound of the stampers thumping, signifying steady work and industry, wages for working men and progress.

The temporary feel of the townships of the west were displaced here by the steady growth of housing and services. Irvinebank had built its second School of Arts Hall and would enjoy its third by the turn of the century. From a humble timber box to a grandiose federation style building that is used to this day, the School of Arts provided the information centre of the town. In the reading rooms, whoever had an interest could read the latest mining journals, financial and market information and the news of the day. At night the hall was used for meetings, dances, plays and concerts.

In Irvinebank, the churches and the pubs kept an even keel with 5 of each being built. In the other towns the pubs outnumbered churches just as the men outnumbered women. Grog outdid God in comforting the aching bodies of hard rock miners by about 10 to 1 and there was always a chance of making a quid at the two up schools that thrived in an atmosphere where incomes were set at the sole discretion of lady luck.

Most of the towns were recycled into other towns. Today the former Walsh District Hospital is a residence in Atherton and the pubs and churches were often dismantled and moved to become pieces of Herberton and parts of Cairns. What was not recycled by man was recycled by nature into termite mounds and ashes. Today the gnarled dry forest species have regenerated to maturity in an altered landscape. Natural history and the history of humankind lie side by side, nature reigning supreme in her tenacity and endurance, men having moved with their things, leaving only the ones under the headstones as a testament among the pock marks and ruins of human progress.

At Irvinebank civilisation continued to thump along with the Loudoun Mill stampers. The tin yielded rich in the company mines and the stampers crushed ore for the independent miners who gouged at the hillsides surrounding the town. The new School of Arts Hall was completed 5 days before Federation Day 1901. Two Brass Bands celebrated this milestone with the colonial fanfare of the day. Men made speeches and women cut the crust off sandwiches for afternoon tea.

John Moffat and his fellow Scots wore stiff collars and maintained the manners of the British elite among the rough and tumble of a multicultural crowd. The Irish toiled in the mines, Italians cut wood for charcoal for the engines and forges. The Scots were engineers, financiers, accountants and doctors; cornishmen laid the bricks of the smelter - chimneys as they had done so well at home. Chinese gardeners supplied fresh produce. In the harsh and remote environment they helped augment the tinned and salted meat diet with precious vitamin, minerals and fibre.

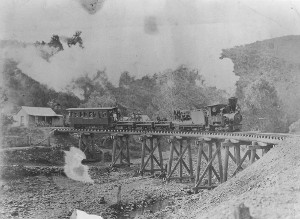

Russians, Swedes and Finns escaped the political turmoil of their homelands by toiling on the tracks of the Chillagoe Railway and the Stannary Hills Tramway which reached Irvinebank on the 28 th of March 1907. This little steam train, on tracks only 2 feet apart, would carry passengers along a tortuous and spectacular track along with the ingots from the Irvinebank smelter, voted the purest metal in the world at the 1907 London World Exposition.

Most of the towns of the western ranges never had a railway reach them. The odd one like Rocky Bluffs never had wheeled traffic into it. The country around the mining sites and crushing mill being too steep and rocky for roads and wheels. Everything was carted in by horse and mule or carried on a mans' back. Huge machinery was brought in parts or made on the spot. To live in these far flung corners of the world, people had to carry the skills to survive in some of the most rugged terrain in the world.

Along the old tracks that carried the traffic of industry and commerce, the washouts of many wet seasons mar the way of man and machine. But the tracks of an occasional horserider passes on the National Trail and as nature reclaims the land, the foot replaces the wheel as it did in the days before white man arrived.

While the towns of the frontier disappeared one by one, Irvinebank lived on. With the sound of the stampers beating like a steady drum throughout most of the 20th century, the buildings were maintained or restored by successive owners and the auspices of the Irvinebank School of Arts and Progress Association which began serving the town in 1883.

Today John Moffat's house on the hill is a museum containing relics of the frontier days and a photographic record of 120 years. Some of these artefacts and images are all that remain to remind us of the harsh days of frontier Australia when North Queensland had its own 'Wild West'.

The paths of the pioneers have widened into broad highways. The forest clearing has expanded into affluent commonwealths. Let us see to it that the ideals of the pioneer in his log cabin shall enlarge into the spiritual life of a democracy where civic power shall dominate and utilize individual achievement for the common good. - Frederick Jackson Turner