As a journalist for the Cairns Post, Hugh A. Borland was a prolific writer and keen historian of North Queensland. Borland was a close friend of Glenville Pike, and like Pike, wrote from a perspective close to the people.

The newspaper provided Borland with a platform and medium for his reporting, and recording of history.

In this piece published in The Northern Herald Saturday, August 19, 1939, as part of a series of historical essays under the title "Pathways of Yesterday," Borland writes his version of the history of John Moffat of Irvinebank.

The article contains one mistake, stating that Moffat set sail for Queensland, Australia in 1865, when actually he arrived in that British colony in 1862. Such a simple mistake may have been due to a typo, and what does it matter?

There are many details written just 21 years after the passing of John Moffat, most likely gleaned from the recent record and memory of contemporaries to make this a valuable and distinguished historical record of the life and times of John Moffat of Irvinebank.

'Si Monumentum Quaeris circumspice.' (If you seek a monument look around).

Such is the inscription on the tomb of Sir Christopher Wren, the builder of St. Paul's Cathedral. Some years ago something on the same lines may have been said concerning John Moffat, the Grand Old Mining Man, of Irvinebank, North Queensland.

John Moffat was born at the Loudoun Mill on the banks of the River Irvine, near Glasgow, Scotland, in the year 1841. As a young man's mind and imagination in those days turned to the outlets which provided, beyond the sea, opportunities for exercising restless spirits so the lively inventive vision of this son of Scotland looked towards Australia.

He sailed for that land in 1865 in the good ship Whirlwind, Captain Bullybrand. For sometime after landing he followed station pursuits and did all sorts of odd jobs. Then he went into business and conducted a draper's shop in Stanley Street, South Brisbane, in partnership with Robert Love under the title of 'Love and Moffat.' Robert Love, it may be of interest to recollect, was for years a well-known resident of Mareeba and local manager for Jack and Newell over a long span of years.

On the discovery of tin at Stanthorpe in the 'seventies of last century John Moffat went to that field and also to the tin mining districts of New England, New South Wales, and his active brain and energy soon made him a prominent figure in these localities. He was the principal in the establishment of the Glen Smelting Company at Tent Hill, near Deepwater, and was also largely interested in many other concerns of that time.

When John Atherton, of Emerald End Station, in North Queensland, indicated to John Newell and party, who were prospecting for tin, the possibilities of its being on the Wild River and so revealed the rich lodes of the Great Northern mine, the stage was being set for the entry of Moffat into northern mining.

Fresh from his achievements in the southern districts, Mr. Moffat entered the industrial life of the Herberton field with zest. Securing a share in the Great Northern mine discovery he was soon engaged in the construction of the first Crushing mill to be placed on the Herberton field. This was erected on practically the same site as the present mill occupies.

In the years 1881 to 1882 he paid a visit to Scotland, travelling thence via Torres Strait in one of the old British India steamers. Whilst away he visited the tin-producing centres of Cornwall and went across to Germany to study methods of treatment and smelting.

Returning to Australia in the Potosi, one of the early steamers of the Orient Mail Line, he went first to Herberton and then on to the newly-opened Irvinebank area. The township that became Irvinebank was to be his home and also his headquarters from which were directed the many different activities kept alive by the very virile Irvinebank Company.

Irvinebank presumably took its name from his birthplace, the bank of the River Irvine in far away Scotland. The Loudoun mill's erection in the township transplanted another Scottish naming within this picturesque northern region.

Meanwhile mining work and vigorous prospecting work had been carried on at Watsonville, Irvinebank and other centres. Mines were being opened up, hills were re-echoing the noise made by fired charges, and the mountains heard the new strange sound of dropping stamps.

In 1884, the big town dam, creating an artificial lake in the heart of Irvinebank, was completed. In the same year the five-head crushing mill was treating stone from the Great Southern, Comet, Adventure, and numerous other mines. Almost simultaneously with these operations a modest tin smelter was erected. This smelting plant was doubled in later years, and the associated calciners and roasting plant, etc., was in active operation till about the year 1920, when all smelting ceased.

Today nothing but the ruins remain. Perhaps some of the old timers will recollect the white bricks set about half-way up the middle smoke stack on which was cut out a group of letters, J. M . and Co. 1884. When the stacks were blown down many years ago, these bricks were rescued by someone and today they form part of a "bird bath" in a home at North Sydney, New South Wales.

In connection with Irvinebank's early history mention must be made of Billy Eales and Jimmy Gibbs, two of the original prospectors. Billy Eales made his home there, was an esteemed citizen for many years, and is lying at rest among the hills of Irvinebank. Several sons are well-known residents of Cairns and district. Jimmy Gibbs resided in Watsonville for a long period and is buried there. The two creeks running through Irvinebank, which united and formed the large town dam covering 13 acres, were named respectively Gibbs' Creek and McDonald's Creek. The latter name was given in recognition of another of the original prospectors.

Montalbion, Muldiva, Glen Linedale, California Creek, Silver Valley, Chillagoe, Mt. Garnet, Coolgarra, Kooboora, Tate Tin Mines, Gurrumbah and many other fields all came into being in due course. Some have had their day and ceased to be, except in the memory of the few surviving old hands. But many of those people today in middle age were born in some of those once prosperous places, and no doubt are proud they were.

Other townships have grown into prominence since then and it is certain that new settlements will yet be created.

John Moffat in stature was a tall man though not in the physical sense a big man. His bigness was in the vision that foreshadowed useful developmental work and in the reserve of mental energy that buttressed the whole structure of building that followed such works as he planned. As a younger man his journeys to the different centres were made on horseback, but in later years he used a buckboard. Then as the railways reached out he used these as much as possible. As age advanced he restricted travelling as much as possible, relying on his assistants. There were no motor cars in those days.

John Moffat was a splendid penman and words, as it were, simply fell off his pen. He had a wonderful command of the English language and the Scottish accent came only to the fore when he was among 'brither' Scots.

He was easy to approach and a good listener. It is recorded by those best able to judge and those who really knew him that very few hard luck tales failed to bring assistance of some kind.

Publicity was shunned by him, advice from his lips was heeded, and any movement for the betterment of the community received ready assistance.

No prospector, no matter how wild his claim to have discovered an Eldorado or Eureka, was ever turned down. In the assay rooms that were always ready for use, the staff made the fullest laboratory tests for whatever possible minerals the stone was supposed to contain. Then invariably there followed an investigating of the locality of the find and its receiving of a fair trial. All sorts of small furnaces, dressing plants, etc., were built to make tests in a small way and John Moffat himself never spared endeavours at all times to get pleasing mutual results by the tests. Tin, copper, bismuth, silver-lead, wolfram, molybdenite, antimony, gold, scheelite, each was of interest.

From the small beginning mentioned, Irvinebank was destined to become a big place and the original five-head battery grew into a 30-head concern with at the time, and as the years rolled on, the most modern dressing plant it was possible to obtain. This plant crushed for years the stone from the famous Vulcan mine and also ore from the company's properties. A further ten head of stamps with its own dressing plant was utilised for the public stone from all the surrounding mines of independent ownership.

There was also a third treatment plant, which had as its crushing unit a large Krupp ball mill. This was used to crush and dress ore from the Governor Norman and other crushings of a soft puggy nature.

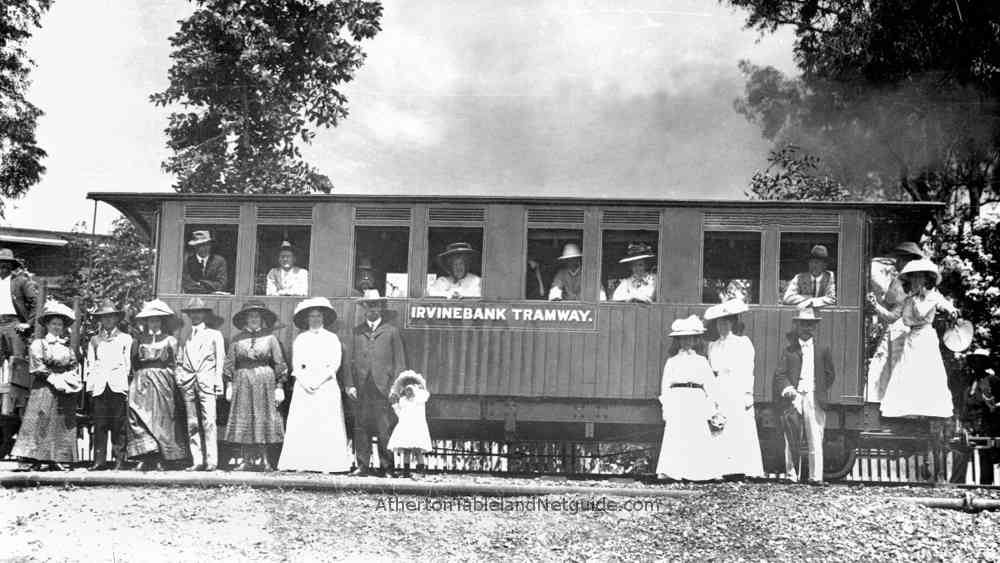

Attached to the batteries were the fine engineer's shops, blacksmith and wheelwright, carpenter and truck repair shops. The latter were necessary units following the linking up of the township with Stannary Hills and so on to the trunk line at Boonmoo. At these shops, and at a small brass and iron foundry were made and repaired the machinery for all the foregoing activities and also for other batteries and mines under John Moffat's direction or owned by other concerns and private individuals.

Models of neatness and simplicity were the books kept by Mr. Moffat and details of the various transactions of the expanding organisations were recorded by him in his own clear style.

Possessed of a wonderful library containing books on all subjects, busy man though he was, Irvinebank's foremost citizen kept in touch with current events. The Moffat-Virtue sheep shearing machine owes much to him. He was the Moffat interested in this invention.

Criticism has often been made of absentee shareholders. John Moffat was not of such individuals. Moreover, he spent his money where he made it. The name-plates on the stamper boxes and other machinery show where these were manufactured and on the Moffat machinery could be seen the names of foundries at Cairns, Townsville, Bundaberg, Maryborough and Brisbane, evidence of his desire to support Queensland industries.

The Laird of Irvinebank knew how to treat his men. One example alone is here quoted. Three engine-drivers, Messrs. Jones, Kirkham and Taylor, worked on shift rotation each with a period of service far exceeding 20 years. And as with them so with others.

A boiler, winch and other machinery went across from Irvinebank to start off Mt Mulligan colliery. The Irvinebank laboratory tested the coal mined and "Betty," the company's locomotive, proved that Mt. Mulligan coal was valuable for railway use. The Moffat interests were cast in divers places, beyond Queensland, and even beyond Australia. Much money was spent, many experiments were made in trying to get payable oil from the shale deposits near Lowmead in the Gladstone district. Ewan, Kangaroo Hills and Mt. Elliott also came within his sphere of outside operations. But it was in the great mining districts, west of Cairns, that his energies found full scope and it is in the Cairns district most of all where one hears the wish expressed that "Another John Moffat would arise."

With the allotted three score years and ten reached, the man who was in effect the Irvinebank Company, ceased his active control and retired to live in Sydney in 1912, contenting himself with other less exacting energies. Among these were efforts to improve and manufacture in the country combs and cutters for sheep shearing machinery, the mechanism of oil boring exploration work and, still clinging to his old calling, endeavours for improvement of zinc smelting and extraction from complex ores.

Age had not dulled the mind nor impaired the vision of his genius. And away up north, among the high hills of Irvinebank and elsewhere, it became markedly apparent that with the retirement of the old gentleman the industrial life of the huge concern would not be as it once was. There was no further expansion, but rather a curtailment of activities, and gradually the Irvinebank Mining Company Ltd. ceased to exist.

In May, 1918, John Moffat, paid a visit to Brisbane, staying there for some weeks. On his way back to Sydney he caught a chill while at Toowoomba and died there on June 28. A few old friends and relatives saw him laid to rest beside the resting place of his uncle. A small black granite stone marking the spot records the following: "Sacred to the memory of John Moffat, of Irvinebank, died June 28, 1918, aged 77 years. 'I have fought the good fight I have finished my course I have kept the faith.'"

His wife, who had been Miss Margaret Linedale, sister of Mr. A. T. Linedale, of mining districts of the far north, did not survive her husband for much more than 12 months. She rests at Waverly, Sydney. Of John Moffat's two daughters, the youngest, Isabel, resides Sydney. Margaret Linedale, who became Mrs. Moffat, has her name perpetuated in the naming of Glen Linedale in the Mt. Garnet district. Mrs. Colin Bate, the elder of the Moffat girls, passed away recently, leaving a young son, who is being cared for by his aunt in Sydney.

Mr. Randolph Bedford wrote thus: "There is a book in John Moffat, this big man of the north. He had knowledge, energy, courage and wisdom, but in the final count his greatness was in his goodness. He respected all men, quarrelled with none, gave to every man his chance, lived cleanly, spoke evil of none, and whenever he came to a stile, he looked for the lame dog. The land he pioneered is mean and ungrateful if it leaves John Moffat's memory only in print that can be forgotten, and in the minds of men who must soon follow him to the 'Place of the Forgotten.' "

Sir Robert Philp, a personal friend, knew of the exceptional qualities possessed by this quiet unassuming nation builder; "One of the first things that John Moffat did when entering a new district was to build dams, realising the importance of ample water supplies for mining developmental work, and the dams he built have been invaluable. He dammed a beautiful sheet of water in front of his house in Irvinebank. He and his wife kept open house at Irvinebank and I have seen as many as thirty guests at the one time. It was like a big hotel excepting that everything was free.

Simple in his habits of life, John Moffat hated affectation. He believed he had a mission in life and that was to help develop the resources of the land he loved. How truly he accomplished that mission will be recognised by all who know anything of his career and will be testified to by hundreds of people scattered throughout North Queensland. Some lasting monument should certainly be erected to the memory of John Moffat and preferably it should be in the great north that owes so much to him."