Randolph Bedford (1868-1941) was a poet, novelist, short story writer, and Queensland state politician. This article titled "John Moffat of Queensland" was originally published by Randolph Bedford as part of his autobiography Naught to Thirty-three in 1944. It was included as part of a collection of articles about Scots in Australia, The Heather in the South, Bill Wannan ed., 1966. Wannan described it as "a rambling piece," and I concur. I have omitted the rambling description of Bedford's travels up the east coast of Queensland, what he observed of the Chinese community in Cairns (as interesting as it is), and his journey by train to Herberton where this excerpt of his article begins.

That is not to say that I have completely excised Bedfords rambling. Despite the title of the article, there is precious little written about Mr Moffat. After a brief meeting, which I believe occurred in 1898, the 30-year-old Bedford immediately takes off alone on horseback to ramble about between Irvinebank and Chillagoe, meeting notable residents Anthony Linedale (John Moffat's business partner and brother-in-law) and the Halpin brothers. Bedford provides wonderful rambling descriptions of the flora, fauna, and geology of the area before ending the piece with a couple of amusing anecdotes about John Moffat, providing us with a delightful insight into Moffat's character and personality.

I rode to Irvinebank next day to see John Moffat, the father of these northern fields. He was a great man; able courageous and modest; and lived mostly on oatcake and tea. Scotland in him, produced a man to be proud of. I thought so much of him, that, visiting Scotland years later, I went to Paisley, because John Moffat was born there. It is nothing against my affection for John Moffat that, as soon as I saw Paisley, a wilderness of brick, and tasted its atmosphere, my enthusiasm deserted me, and I left it by the next train.

Moffat came to Australia as a Scotch youth of eighteen or so. After service in a Brisbane store he started business, store-keeping and ore-buying in the newly discovered field of Quart Pot Creek - now Stanthorpe. All his life he was unable to listen unmoved to a hard-luck story, and as he trusted everybody, he, when the tin field went down, descended with it. He was bankrupt, and paid ten shillings in the pound. He went north, reaching Herberton in the early days of a tin field; established a mill there, and one at Irvinebank; and others on smaller fields that lived and died quickly. He had been working Chillagoe for years, before southern capital was invited to build a railway and equip smelters. With charcoal fuel, he had smelted nearly ten thousand tons of high grade copper ore in his little smelters at Calcifer (or rather, Cal-cu-fer - lime, copper, iron); and at Girofla. He had developed Mt. Garnet into what looked like a permanent copper mine, fifteen per cent copper, and twenty ounces silver to the ton; the silver occurring native, in the cleavages of the bornite and erubescite - ores of copper.

On the Chillagoe and Garnet floats - which were to come later - he received two hundred thousand Chillagoe shares, which at their peak were valued at 46/-, and one hundred thousand Garnets, which at their peak were valued at 87/-. He didn't sell. Later, when I asked him "why," he replied that if they were worth anything he would hold them, and if they were worth nothing he would not unload them on anybody. First and last he was interested in the mines, and not in the share market. He took two millions worth of ore out of the scores of mines he developed, and put it all back again into the earth. He had - although free in law from obligation - paid all his old creditors in full, with interest added. He is one of the few men I ever met whose life was a monument to honesty. There has rarely been as fine a man in any country as this immigrant from Paisley.

I met him on arrival in Irvinebank and he liked me at once, though deprecating the fact that I seemed to be always in a hurry. I had bought at Herberton, a silvergrey horse named "Freetrader." A bad name, and he was a bad horse to ride. Staunch and tireless, but I think he must have packed tin concentrates, and that destroys a horse's pace, except as a pack horse.

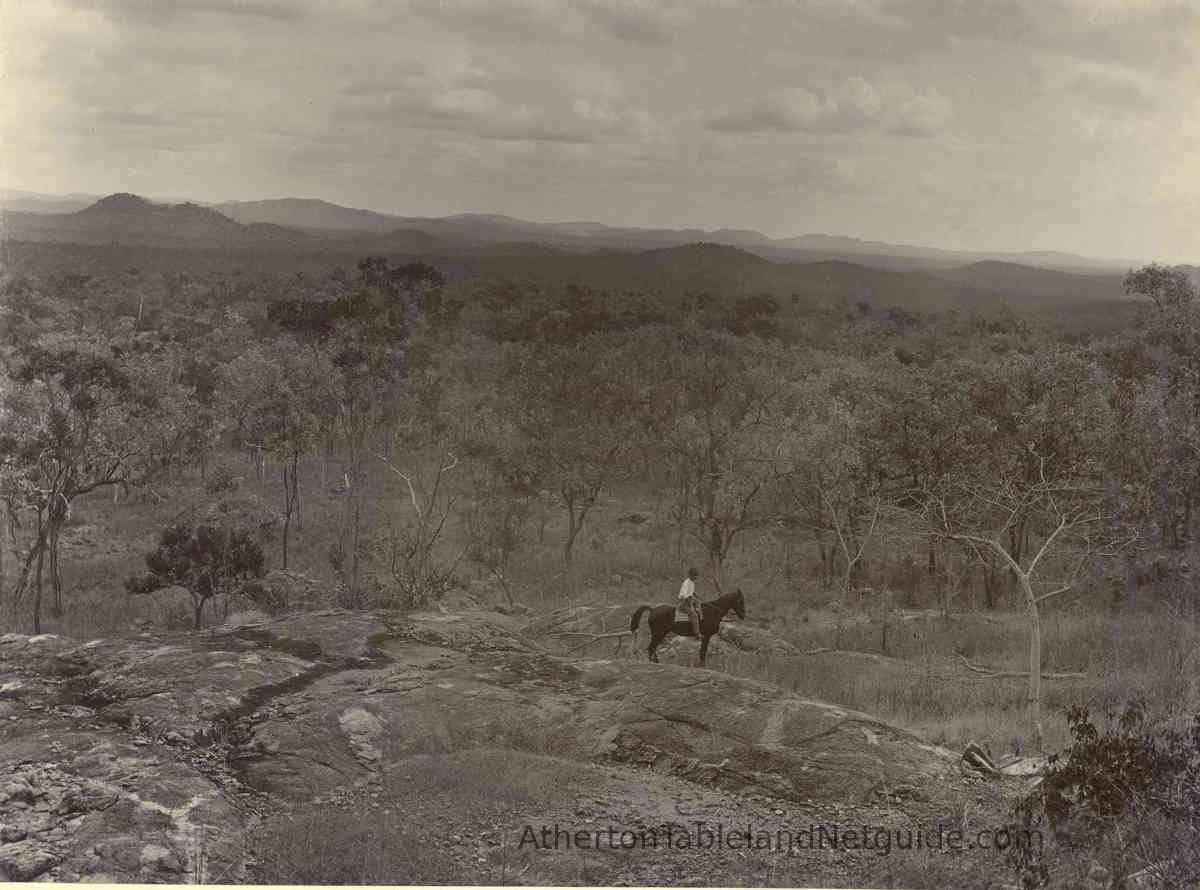

Twenty miles was not long enough for me to find him out, and so, although Mr. Moffat asked me to stay for a few days and drive there, I felt that I must make the pace, and rode off on the seventy mile run to Chillagoe. The track lay through Mont Albion, an old silver field, and over the roughness of the Strawbed and Featherbed ranges - the Featherbed having the largest stones on it - I went through Muldiva to Calcifer.

There, I was met by Anthony Linedale, who lived at Girofla - sixteen miles away. Freetrader, the journey done, lay down, and I wanted to do the same, but Linedale wanted to go home, and he offered me a fresh horse, and pride made me mount. The camel-motion of Freetrader gave me two aches for every millimetre of dorsal surface, but Linedale rode away, and I followed. It was at cantering pace that we covered the sixteen miles without drawing rein; and when, at two miles out, the moon rose behind us, I forgot every ache, and enjoyed the ride so much that I remember today that feeling of high adventure.

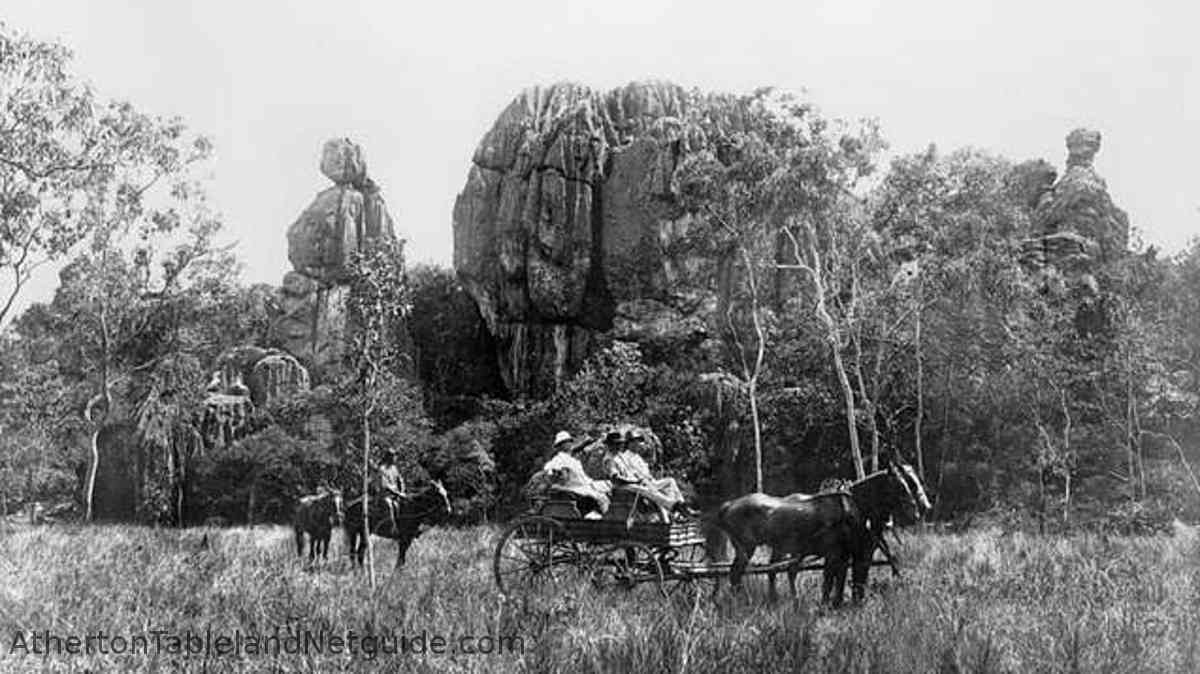

The track lay through avenues in the limestone that towered above us, in cathedrals and abbeys and castellated roofs. Moonlight, scented gale, firm red track below, and the horse with all the pleasure of the rider on his back. Wind, light, scent, speed, strength, ripple and swing. And I slept without an ache that night.

I had a fortnight in that new country, and loved it all, but the long rides through the limestone. I once wasted - or used - nearly half a day watching, myself unseen, a bower-bird play with all the bright things he had collected; bits of copper ore, the glass stopper of a bottle, fragments of coloured stone. There were rifted lime rocks, and the cotton tree producing its glossy yellow flowers from the seeming barrenness. Great fig trees grew near every cavern in the limestone defying drought; their roots went waving and searching down the caves, feeling for water as an elephant uses his trunk. The iron soil grew poison peach and rosellas, lilac and amaranth.

In the rains, life broke around us everywhere. In the termitaria, where the white ants hid their pulpy bodies safe by an imprisonment measured by the sun, there was action. In the long spear-grass, where there were not tracks, we rode into webs of the great yellow spider - webs strong enough to hold the grasshopper in his leap; webs swung just high enough to catch the horseman. It was unpleasant to feel that greasy web upon the face; but the great spider either threw himself, lunatic and bloated with terror, into the grass, or was broken against the pommel by the rider's hand, and that did not feel pleasant, either. Beetle, grasshopper, butterfly, and bird; black and sulphur-crested cockatoo, and the galah; little painted finches, brilliant as enamels of China; the squatter pigeon, so paralysed by fear of the oncoming horseman, that he may be killed by the blow of a whip; magpies and rosellas. And there were in all the forest land, bands of jays, variously known as "Happy Families" or the "Twelve Apostles;" that chatter always for the duration of sunlight. There were flies as a plague, but a cylindrical gossamer veil, depending from the hat-brim, and a running-string to keep them out at the neck, made life endurable. But I did object to the spear-grass. Finding a traveller, it leaves the spears of its seed in his clothing; so that he may, cursing, pull them out at the next halt, and so make spear-grass grow where non grew before.

On the road from Irvinebank to Koorboora was the little cattle run of Con Halpin and his brothers; all of them old men; but upright as saplings, and born to the saddle. In the rains I once stayed at the homestead for a night. Next morning, after a bath of buckets of water emptied over the subject, Con brought in two bottles of rum, and dispensed of it. One of the brothers tabled a huge piece of corned beef, and a great damper; the other brother brought a bucket of tea; the gin, who had spread the cloth, and placed the knives and forks and plates and pannikins, arrived with two or three dozen hard-boiled eggs filling a great billy can. She emptied the can of eggs on the table and said:

Brekfus, boss!

Other butlers elsewhere introduce the food with the formula, Breakfast is served, my lady

; but the Halpin gin was quite as serviceable, and the good digestion of the bush waited on appetites sharpened by rum.

John Cairns was a close friend of Moffat's, and Cairns drank whisky, as did all men I met in the north, excepting only John Moffat, who lived on oatcake and tea. I saw John Moffat once drinking ginger beer, but it was in a moment of forgetfulness. He disliked hard liquor intensely, and yet was very kind to the temporary victims of it.

Two loafers suffering a recovery got a bucket full of titanic iron, and offered to sell it to John Moffat as wolfram. They begged him to buy, and told a tale of the misery of suffering a recovery while penniless.

Give us ten bob for the wolfram, Mr. Moffat.

Verra well ... There it is.

Where'll we put the wolfram, Mr. Moffat?

Oh! just dump it anywhere.

They went down the house stairs, dumped the wolfram, and hurried to the place of rum.

I told y' we'd put it over the old blanker, Bill,

said one of the ruffians. And from the balcony they heard the voice of Moffat:

'Tis all right! The old blanker knew all about it, before y' said a word.

They ran away.

John Cairns, arriving at Irvinebank late one winter night from Koorboora, rain-saturated and chilled was welcomed by Moffat.

Don't take cold, John,

said Moffat. Into a hot bath, and I'll bring something to warm ye.

Cairns, under the hot shower, was merrily expectant.

A great man, John Moffat,

said he. Hates liquor, and yet he'll smother his dislike of it and send me whisky, because I'm cold. A good man, John.

And then Moffat's voice was heard at the bathroom door.

Put your hand out, John,

said he to Cairns, who extended his hand out for the toddy. It's a bottle o' acetic acid; rub yourself all over with it, and you'll be right.

John Cairns, telling me the story, said that it was the only thing for which he ever had to forgive Moffat; but he could not forget it.

If you enjoyed reading this page, please show your support and donate the price of a cup of coffee for the author: