The burial of the blacks - Black mummies - Sorcerers or wizards - Myths and legends - The doctrine of the Trinity in New South Wales - The belief in a future life among the blacks.

On our way home from an expedition we discovered a grave in a "white ants'" hill. The entrance was about a yard high. It was built on the side of the anthill, extending about half way up, and had a sloping front. In front of the opening large pieces of the bark of the teatree were placed, on which heavy stones were rolled in order to keep wild dogs from getting to the corpse. In a tree near the grave hung a capacious basket. This led me to think that the Australian natives probably believe in a future life, and I examined this basket to see whether provisions had been left in it, but I found it empty. I asked the natives whether there had been food in the basket, so that the deceased might have something to eat, but this was an idea which they could not comprehend.

They informed me that a child was buried here. The parents were so much grieved at the loss of their child that they did not care to keep the basket in which they had carried it, and had accordingly left it beside the grave.

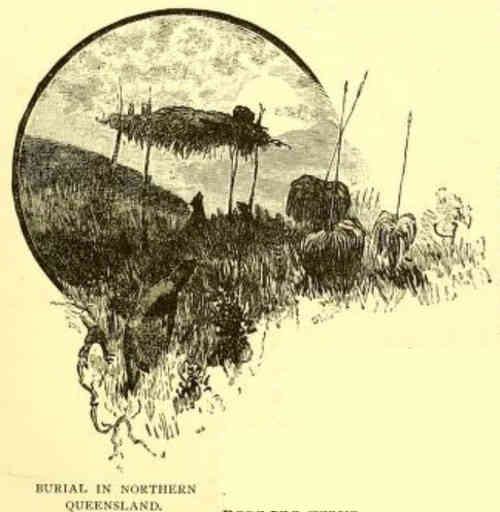

The Australian natives usually bury their dead, but they invariably strive to avoid letting the corpse come into direct contact with the earth, and the dead body is therefore wrapped in bark or other materials. The graves are not very deep, and sometimes have a direction from east to west, and the foot of the grave is toward the rising sun. In some parts of Queensland two sticks, painted red and about a yard high, arc erected near the grave, and on the tops of the sticks feathers of the white cockatoo are fastened. If the deceased was a prominent man, a hut is sometimes built over his grave. The entrance, which faces the east, has an opening through which a grown person may creep. In some parts of Australia the dead body is placed in a sitting posture, and a mound is built over it. There are also tribes which bury their dead in a standing position. Near Rockhampton I saw several graves not more than a foot deep, in which the feet were directed toward the rising sun. Hills are usually selected as burial-places. At Coomooboolaroo the dead bodies both of women and men are laid into graves as long as the corpses, about a yard under the sod, and wrapped in pieces of cloth or bark. The graves are filled with small tree-trunks up to the level of the ground, and then a thin layer of soil is laid on the top.

East of Fitzroy River women are laid in an open trench, the earth having been dug out with a " yam stick " and neatly piled up all round; the body is in this way left quite exposed, and the legs are bent upwards. The grass all round for a couple of yards or more is removed, leaving the ground quite bare; this is probably done to protect the grave in case of bush-fire. After a time their relations come and gather the bones, cut a hole in a hollow tree, and put the bones into it. The hole is then filled up with grass, and twigs or sticks are laid on the top to keep the grass in. The tree-trunk above and below the hole (around which the bark is cut away) they paint with red or red and white colours.

An old warrior who has been a strong man and therefore much respected by his tribe, is after his death put on a platform made with forked sticks, cross-pieces, and a sheet or two of bark; he is hoisted up amidst a pandemonium of noise, howling, and wailing, besides, much cutting with tomahawks and banging of heads with nolla-nollas. He is laid on his back with his knees up, like the females, and the grass is cleared away from under and all round. The place is now for a long time carefully avoided, till he is quite shrivelled, whereupon his bones are taken away and put in a tree. The common man is buried like a woman, only that logs are put over him and his bones are not removed. Young children are put bodily into the trees.

The fact that the natives bestow any care on the bodies of the dead is doubtless owing to their fear of the spirits of the departed. In some places I have seen the legs drawn up and tied fast to the bodies, in order to hinder the spirits of the dead, as it were, from getting out to frighten the living. Women and children, whose spirits are not feared, receive less attention and care after death.

In several tribes it is customary to bury the body where the person was born. I know of a case where a dying man was transported fifty miles in order to be buried in the place of his nativity. It has even happened that the natives have begun digging outside a white man's kitchen door, because they wanted to bury an old man born there. In Central Queensland I saw many burial-places on hills. Such are also said to be found in New South Wales and in Victoria. These burial-grounds have been in use for centuries, and are considered sacred.

In South Australia and in Victoria the head is not buried with the body, for the skull is preserved and used as a drinking-cup. It is a common custom to place the dead between pieces of bark and grass on a scaffold, where they remain until they are decayed, and then the bones are buried in the ground. In the northern part of Queensland I have heard people say that the natives have a custom of placing themselves under these scaffolds to let the fat drop on them, and that they believe that this puts them in possession of the strength of the dead man.

A kind of mummy, dried by the aid of fire and smoke, is also found in Australia. Male children are most frequently prepared in this manner. The corpse is then packed into a bundle, which is carried for some time by the mother. She has it with her constantly, and at night sleeps with it at her side. After about six months, when nothing but the bones remain, she buries it in the earth. Full-grown men are also sometimes carried in this manner, particularly the bodies of great warriors. This is done, for instance, in the southern part of Queensland, and a mummy of this kind may be seen in the Brisbane Museum. Mr. Finch-Hatton relates in Advance Australia that when an old warrior dies he is skinned with the greatest care, and after the survivors have eaten as much of him as they like, the bones are cleaned and packed into the skin, and thus the remains are carried for years.

The natives in the neighbourhood of Portland Bay, in the south-western part of South Australia, cremate their dead by placing the corpse in a hollow tree and setting fire to it. This is also done by the tribes west of Townsville.

In connection with this, I am reminded of Lucian's words: "Various people have various modes of burial. The Greeks cremated their dead; the Persians buried them; the Hindoos anoint them with a kind of gum; the Scythians eat them; and the Egyptians embalm them." Here we are given nearly all the modes of burial which have existed both among civilised people and among barbarians, and strange to say, we find all these modes represented among the savages of Australia.

The natives of Australia have this peculiarity, in common with the savages of other countries, that they never utter the names of the dead, lest their spirits should hear the voices of the living and thus discover their whereabouts.

There seems to be a widespread belief in the soul's existence independently of matter. On this point Fraser relates that the Kulin tribe (Victoria) believes that every man and animal has a murup (ghost or spirit), which can pass into other bodies. A person's murup may in his lifetime leave his body and visit other people in their dreams. After death the murup is supposed to appear again, to visit the grave of its former possessor, to communicate with living persons in their dreams, to eat remnants of food lying near the camp, and to warm itself by their night fires1. A similar belief has been observed among the blacks of Lower Guinea. On my travels I, too, found a widespread fear of the spirits of the dead, to which the imagination of the natives attributed all sorts of remarkable qualities. The greater the man was on earth the more his departed spirit is feared. Of the spirits of those long since departed there is no dread. Upon the whole, it may be said that these children of nature are unable to conceive a human soul independent of the body, and the future life of the individual lasts no longer than his physical remains.

1Transactions of Royal Society of New South Wales, 1882.

In the various tribes are so-called wizards, who pretend to communicate with the spirits of the dead and get information from them. They are able lo produce sickness or death whenever they please, and they can produce or stop rain and many other things. Hence these wizards are greatly feared. Mr. Curr has very properly called attention to the influence of this fear of witchcraft upon the character and customs of the natives. It makes them bloodthirsty, and at the same time darkens and embitters their existence. An Australian native is unable to conceive death as natural, except as the result of an accident or of old age, while diseases and plagues are always ascribed to witchcraft and to hostile blacks.

This superstitious fear causes and maintains hatred between the tribes, and is the chief reason why the Australian blacks continue to live in small communities and are unable to rise to a higher plane of social development.

In order to be able to practise his arts against any black man, the wizard must be in possession of some article that has belonged to him - say, some of his hair or of the food left in his camp, or some similar thing. On Herbert River the natives need only to know the name of the person in question, and for this reason they rarely use their proper names in addressing or speaking of each other, but simply their class-names. The wizard is, as a rule, a man far advanced in years, but I knew a youth of only twenty who enjoyed a great reputation for his sorcery. The wizard is also the physician of the tribe, and imagines that he can cure all diseases and that he has great power over the "devil-devil."

I once met a black man who told me that he personally had been the victim of strange wizards, and that ever since that time he had been a sufferer from headache. One afternoon, many years ago, two wizards had captured him and bound him; they had taken out his entrails and put in grass instead, and had let him lie in this condition until sunrise. Then he suddenly recovered his senses and became tolerably well, a result for which he was indebted to a wizard of his own tribe, who thus proved himself more powerful than the two strangers. The blacks call an operation of this kind kobi, and a man who is able to perform it, and who, as a matter of course, is very much respected and feared, is said to be "much kobi," a fact of which I, too, used to boast, for the purpose of maintaining my importance in the eyes of the blacks, and in this I was successful, at least in the beginning. "Kobi" was the most dreadful thing imaginable. It usually ended in death, and although the life of the victim might be saved, he would for ever after have a reminder in the form of constant headache.

An old warrior in a tribe not far from Rockhampton was taken very ill. The tribe being at the time near a station, asked the manager, who was a friend of mine, to give the sick man some medicine. "Holloway's pills," the usual medicine in the bush, was accordingly supplied to him, but without making him any better. The doctor of the tribe had then to bring his powers into action. All the blacks attributed his illness to some strange black-fellows who had put some pieces of broken glass into him, and these the doctor was now willing to take out, in order to effect a cure. The old man was laid in front of a big fire; all the members of the tribe had placed themselves solemnly round him, some of his five "gins" crying. Suddenly out of the darkness appeared a huge black-fellow dressed up to his eyes in paint and feathers and carrying a long spear in his one hand, while in the other he held a small pouch made out of a kangaroo's scrotum. Then began the most awful row one can imagine - crocodile tears flowing in streams. The doctor placed himself within reach of the patient, stretched out his spear and touched him with the point, and all the noise at once ceased; the eager look on all the dark faces round was something to see. Every time the doctor raised his spear he produced a piece of broken glass from his hair and put it into the bag, this performance being followed by a great yell from all those assembled. tie produced altogether seven pieces of glass, and the crowd uttered a yell for each piece. When all was over, the doctor disappeared into the darkness, and the sick man recovered. All the blacks believed that he had drawn these pieces up the spear into his hair, and to try to convince them of the absurdity of such an opinion only made them sulkily say, "White-fellow stupid fellow."

Strange to say, many of the civilised blacks believe that they will be changed hereafter into white men - that they will "jump up white-fellow," and it is also an interesting fact that many tribes use the same word for "spirit" and for "white man." It has frequently happened that the savages have taken white men to be their own deceased fellows, which confirms the theory prevalent in many parts of Australia that the natives believe in a future life. Near a station in Central Queensland the white population observed that a black woman repeatedly brought food to the grave of her deceased husband.

The Australian blacks do not, like many other savage tribes, attach any ideas of divinity to the sun or moon. On one of our expeditions the full moon rose large and red over the palm forest. Struck by the splendour of the scene, I pointed at the moon and asked my companions: "Who made it? "They answered: "Other blacks." Thereupon I asked: "Who made the sun?" and I got the same answer. The natives also believe that they themselves can produce rain, particularly with the help of their wizards. To produce rain they call milka. When on our expeditions we were overtaken by violent tropical storms my blacks always became enraged at the strangers who had caused the rain. Even my naive friend Yokkai once boasted that he and the young Mangola-Maggi, who was a wizard, had produced rain to worry other blacks.

I never succeeded in discovering myths and legends among the blacks of Herbert river; but they are close observers of the starry heavens, and I was surprised to find that they had different names for the planets, distinguishing them by their size. In other parts of Australia the fancy of the natives makes the stars inhabited, and in this way several beautiful myths have been developed.

The southern tribes of Australia not only occupy their minds with myths and legends, but they also have definite religious notions. Some very interesting information in regard to the idea of a God cherished by these southern natives has been furnished by Mr. Manning, who in 1845 discovered among some tribes of New South Wales a doctrine of the Trinity, which bears so striking a resemblance to that of the Christian religion that we arc tempted to take it to be the result of the influence of missionaries.1 But according to the author, the missionaries did not visit these tribes until many years later. They recognise a supreme, benevolent, omnipotent Being, Boyma, seated far away in the north-east on an immense throne made of transparent crystal and standing in a great lake. He has an omniscient son, Grogoragally, who brings men to his father's throne, to be judged by the latter, and the son is the mediator. There is also a third person, half human, half divine, Moogeegally, who is the great lawgiver to men, and who makes Boyma's will known to them. They also believe in a hell with everlasting fire, and a heaven, where the blessed dance and amuse themselves. Several other authors agree that the southern tribes of Australia believe in a supreme good Being, though they have nowhere found a religious system so perfectly developed as the one above described. Mr. Ridley's statements concerning the Kamilaroy tribe are particularly remarkable. These natives believe in a creator, Bhaiame, who is to judge mankind. The word is derived from baio, to cut or make - thus creator, - and is distinctly identical with Manning's Boyma.

1Transactions of Royal Society of New South Wales, 1882.

Others again, as for instance Mr. Mann (in New South Wales), who has made a thirty years' study of the blacks, deny that the natives have any religion whatever except fear of the "devil-devil."

It is not easy to understand this want of agreement among the authorities. If, however, the above-mentioned theory, that the south part of Australia is inhabited by a higher and more developed race than that in the north, is correct, then this supplies the solution of the problem.

As to the natives on Herbert river, it is my opinion that they do not believe in any supreme good Being, but only in a demon, and it was even difficult for them to give any definite account of this devil. On the other hand, it must be admitted that the natives are very reluctant to give any information in regard to their religious beliefs. They look upon them as secrets not to be divulged to persons not of their own race. Hence there is a possibility that they believed in a God and had more developed notions than I suspected, but I do not regard this as probable. Besides, I have evidence from various sources that the same is the case with other tribes.

Mr. George Angas1 says of the tribes on Murray river in South Australia: "They appear to have no religious observances whatever. They acknowledge no Supreme Being, worship no idols, and believe only in the existence of a spirit, whom they consider as the author of ill, and regard with superstitious dread. They are in perpetual fear of malignant spirits, or bad men, who, they say, go abroad at night; and they seldom venture from the encampment after dusk, even to fetch water, without carrying a fire-stick in their hands, which they consider has the property of repelling these evil spirits."

1Savage Life and Scenes in Australia and New Zealand. London, 1850, vol. i. p. 88.

In The Fifth Continent, p. 69, Mr. Charles Eden appears to me to use rather strong language when he says: "I verily believe that we have arrived at the sum total of their religion, if a superstitious dread of the unknown can be so designated. Their mental capacity does not admit of their grasping the higher truths of pure religion."

Mr. Curr is of the opinion that the religious ideas which people claim to have found among the Australian natives are simply the result of the influence of the white man, the ideas being modified to suit the fancy of the natives.

At all events, it is certain that neither idolatry nor sacrifices are to be found in Australia. Nor have the natives, so far as I know, ever been seen to pray.

In conclusion, I will give a brief account of a conversation which I had one evening with the Kanaka at Herbert Vale, for in my estimation it throws some light on this question. In his native home, in the far-off South Sea Islands, he had received instruction from missionaries, but had not been converted to Christianity. He said he did not like the missionaries. On this occasion - it was a mild, starlit night, such a one as can be seen only in the tropics - he asked me if it was true that we would some day go to the stars up there. I explained to him what Christianity teaches in regard to a life hereafter. "There is a much better place up there after death," he remarked. Some of the natives were standing round us with their mouths wide open. Suddenly he burst into laughter, and pointing with one hand to the glittering stars, said: "The blacks do not believe that there is anybody above us up there."

The objection might be made to this statement, that the natives, particularly the older ones, had secrets which they were unwilling to divulge to the younger members of the tribe, with whom the Kanaka mostly associated, and that he consequently was not acquainted with the religious ideas of the tribe, but it appears to me that so important a matter as the belief in a God could scarcely have escaped his observation, for he was constantly with them both by day and by night. He spoke their language fluently, was married to a woman of their tribe, and had become wholly identified with them in customs and habits of thought