Introductory - Voyage to Australia - Arrival at Adelaide - Description of the city - Melbourne, the Queen of the South - Working men - The highest trees in the world - Two of the most common mammals in Australia.

On May 24, 1880, I went on board the barque Einar Tambarskjelve bound from Snar Island near Christiania to Port Adelaide with a cargo of planed lumber. I carried with me a hunter's outfit, guns, ammunition, and other articles necessary for the chase, furnished me by the University of Norway, as well as some northern bird skins in order to inaugurate exchange with Australian museums. Sailing in the north-east trade-winds, a sunset in the tropics, or a mild starlit night on the ocean with a blazing phosphorescent sea, do not fail to make a strong impression. Then passing the Pacific belt of the ocean, where a dead calm is suddenly interrupted by the most violent storm, you soon reach, by the aid of the south-east trades, the region of the westerly winds. The Southern Cross and the cloud of Magellan. The gigantic sperm-whale, whose huge head now and then appeared above the surface of the water, and the albatross, whose glorious flight we never ceased to admire, heralded our arrival within the limits of the Southern Ocean. Cape-doves, albatrosses, and gulls accompanied us for weeks together.

The passage had, however, at times its dark sides. On August 17, at six o'clock in the morning, we were overtaken by a most violent gale. All the sails, except the close-reefed topsails and foresail, were taken in. We shipped many seas. The stairs to the quarter-deck were crushed; one wave broke through two doors in the companion-way to the steerage, another set all the water-casks afloat in the maddest confusion, a third filled the galley, so that the cook found himself waist-deep in water. The fire was extinguished, and the food was mixed with the salt water. Several times the seas broke through our main cabin door, filling my cabin with water, making boots, socks, books, and other articles swim about in all directions.

On a long journey one gets tired of the sea, this "desert of water," as the Arab calls it - and we long to set foot again on terra firma. According to the calculations of the captain we were fifty geographical miles from the coast of Australia, when one morning we perceived for the first time the smell of land, in this instance a peculiarly bitter but mildly aromatic odour, as of fragrant resin. This fragrance, doubtless, came from the acacias, which at this time were in full bloom. For by the aid of the wind these trees, particularly Acacia fragrans, diffuse the fragrance of their flowers to a great distance, and this morning there was blowing a fresh, damp breeze directly from the land.

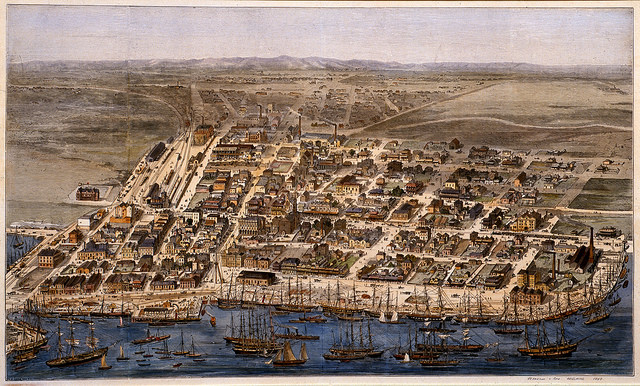

On the afternoon of August 29 we got sight of land. In the evening we saw the lighthouse on Kangaroo Island; followed by dolphins we navigated through Investigator Straits, and on the afternoon of the next day we anchored outside Port Adelaide. As it was raining, we contented ourselves with viewing the town from the distance. Our eyes involuntarily rested on a number of chimneys, an evidence of extensive manufactories.

What most interested me here was the Botanical Garden, which I visited the same day. The weather was splendid, the rays of the sun were reflected in large ponds, where the water-fowl were swimming among papyrus and Babylonian weeping-willows. The parrots chattered in their cages, and displayed their brilliant plumage; the birds sang in the cultivated bushes of the garden, and the frogs croaked with that harsh, strong note, which seems especially developed in tropical lands. There was a life, a throng, an assemblage of dazzling colours, which could not but make a deep impression on a person whose eyes for a hundred days had seen nothing but sky and water.

This fine garden contains forty-five acres, and is excellently managed by Dr. R. Schomburgk, celebrated for his travels in British Guiana. In the "palm-house," built of glass and iron, are found tropical plants. The most beautiful and most imposing part of the park is the so-called garden of roses, a large square enclosure surrounded by garlands of tastefully-arranged climbing roses. Here is an abundance of varieties, beginning with the tallest rose-bushes and ending with the smallest dwarf-roses, and the colours vary from the most dazzling white to the darkest red or almost black.

Among the trees familiar to me in this park were an alder and a birch. They stood very modestly, just putting forth their leaves in company with grand magnolias in blossom, elegant araucarias, and magnificent weeping-willows. The hot-houses near the superintendent's dwelling were admirable, and presented a wealth of the greatest variety of flowers from all parts of the world, but mainly from Australia.

Some groups of fine bamboo particularly attracted my attention. The park is visited by several thousand people every Sunday afternoon.

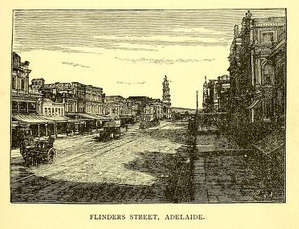

Adelaide, containing about 60,000 inhabitants, is a very regularly laid out city. All the streets cross one another at right angles, and are very broad. Along the gutters railings are placed, to which people may hitch their horses. Even servants go to market on horseback with baskets on their arms.

The residences are constructed in a very practical manner, suited to the demands of the climate, with verandahs and beautiful gardens. In many parts of the city there are public reading-rooms, where the latest newspapers may be found. In the forenoon these reading-rooms are always full of people, particularly of the working classes.

The city cannot fail to make a favourable impression upon the traveler. It is clean and elegant, corresponding to its feminine name Adelaide. The inhabitants are unusually amiable, and they are renowned for their hospitality; and this is saying a great deal in so hospitable a land as Australia.

From Adelaide to Melbourne is a three days' journey, and early one morning I went on board a steamer bound for this port. Once there we immediately perceive that we have come to a metropolis, for the flags of all nations are unfurled to the breeze in its harbour.

The International Exhibition was to be opened in a few weeks, and in the distance we could already see the great cupola of the building looming up above the rest of the city. Great clouds of dust appeared in the streets, giving us an idea of Melbourne's dry climate. After a slow voyage up the shallow Yarra river, during which we actually stuck in the mud once or twice, we finally landed at the wharf.

Melbourne with its suburbs has only 300,000 inhabitants, but has the appearance of being much larger on account of its broad and straight streets and its numerous parks, and magnificent public buildings.

The first building attracting our attention is the Library, a noble structure in classical style, but the first thing the inhabitants want the stranger to notice is the Post Office and Town Hall. The question is being perpetually asked: "Have you seen the Town Hall and the Post Office?" The Assembly Room in the Town Hall contains one of the largest organs in the world; it has 4373 pipes.

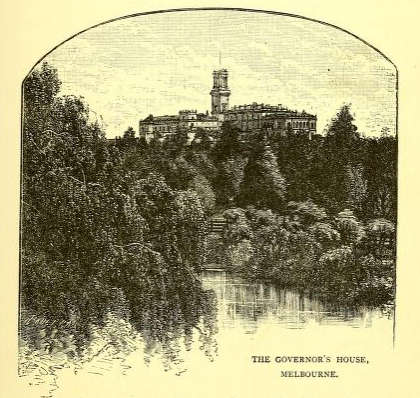

The residence of the Governor occupies a commanding height, and is surrounded by a large park, which is directly connected with the Botanical Garden.

The University, which is attended by about 400 students, has, since 1880, been open to women, who are now admitted to all the courses except medicine! It possesses a large museum, where the animals are in part set up in groups representing scenes from their daily life, in a most instructive arrangement. Here can also be seen a fossilised eggs of the extinct gigantic bird from Madagascar, the Aepyornis maxiimis.

The city contains a number of magnificent churches, hospitals, and benevolent institutions. The streets are large, wide, and have immense gutters. It has been well said by an author that Melbourne is London seen through the small end of the telescope.

People seem to be very busy, and move through the streets with great rapidity. Melbourne is a city of enjoyments and luxuries, equipped with great elegance and comfort ; everything suggests money and the power of wealth. There is no article of luxury which is not to be found here, from Norwegian herring to champagne in every degree of dryness.

Among sports, horse-racing ranks first, and not a week passes without one or more races on the celebrated Flemmington racecourse, near the city, taking place. Every year, in the beginning of November, about 120,000 people come together to witness the great Melbourne Cup race, where fortunes are lost and won.

The whites born in Australia are gradually becoming a distinct race, differing from other Englishmen. They have a more lively temperament, and are slighter in frame, but tall, erect, and muscular. I also observed in Queensland that some of the children had a tendency to the American twang. The Australians pay great attention to travellers visiting their country, and they are very proud of showing its attractions. Thus a stranger may, as a rule, count on getting a free pass on all the railroads. The ladies are free and easy in their manners. They are frank and confiding, and their acquaintance is quickly made. Their friendship, once gained, may be relied on, and they are untiring in their acts of kindness.

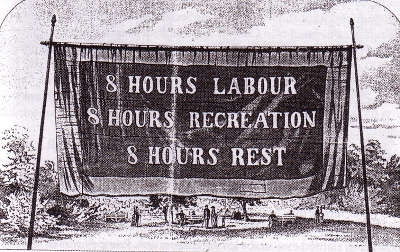

In no other place in the world do the labouring classes have as much influence as in Victoria; for the working men in fact govern the colony. As a rule, they are well educated, and keep abreast of the times, but still their administration of affairs has not always been successful. The economical condition of the labouring classes in Melbourne is excellent, but they are rather fond of intoxicating drinks. I am able to give an example, showing how the people of Australia keep themselves informed on public questions. I once spoke to a labourer whom I met on the street in Melbourne, and as he noticed that I was a stranger, he asked me where my home was. When he learned that I came from Norway, he exclaimed: "Oh, we know Norway very well, and the Norwegian scheme!" He then explained this to me as best he could. I afterwards learned that Victoria, in 1874, was on the point of adopting a parliament like the Norwegian, with one chamber which divides itself into two bodies (the odelsthing and lagthing), a proposition which was on the point of being carried.

The climate of Melbourne is not particularly warm, though during the summer excessively hot winds from the interior of the continent may blow for a few days, and not infrequently children die from the heat at this time. The sudden changes of temperature, peculiar to the southern part of Australia, also annually demand their victims, though upon the whole the climate must be regarded as very healthy.

Before leaving Melbourne I made several excursions far into the colony. On one of these I visited the celebrated mining town Ballarat, the place which marks the first epoch in the history of Victoria, and of all Australia for that matter, for it was the gold which especially drew the attention of the world to the new continent.

Since 1851 the annual production of gold in Australia has averaged ten million pounds sterling.

No traveller should neglect to view "the highest trees in the world," for it is easy to see them near Melbourne. Eucalyptis amygdalina grows, according to the famous botanist Baron F. v. Mueller, to a greater height than the Wellingtonia sequoia of California. Trees have been measured more than 450 feet high. Though these gum-trees are without comparison the highest in the world, they must yield the place of honour in regard to beauty and wealth of foliage. They send forth but a couple of solitary branches from their lofty tops. Thus the Wellingtonia retains the crown as the king of the vegetable kingdom. F. v. Mueller says of Eucalyptus amygdalina: "It is a grand picture to see a mass of enormously tall trees of this kind, with stems of mast-like straightness and clear whiteness, so close together in the forest as to allow them space only toward their summit to send their scanty branches and sparse foliage to the free light."

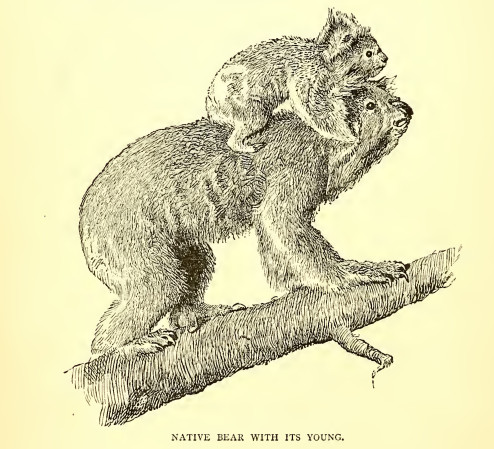

At a sheep station about 100 miles from Melbourne I made the acquaintance of two of the most common mammals of Australia. One day I went out hunting with a son of the friend that I was visiting. We learned that a koala or native bear {PJiascolarctiis cinereics) was sitting on a tree near the hut of a shepherd. Our way led us through a large but not dense wood of leafless gum-trees. My companion told me that the forest was dead, as a result of "ring-barking." To get the grass to grow better, the settler removes a band of bark near the root of the tree. In a country where cattle-raising is carried on to so great an extent this may be very practical, but it certainly does not beautify the landscape. The trees die at once after this treatment, and it is a sad and repulsive sight to see these withered giants as if in despair stretching their white barkless branches towards the sky. When we came to the spot, we found the bear asleep and perfectly calm on a branch of a tree opposite the shepherd's hut. One must not suppose that the Australian bear is a dangerous animal. It is called "native bear," but is in nowise related to the bear family. It is an innocent and peaceful marsupial, which is active only at night, and sluggishly climbs the trees, eating leaves and sleeping during the whole day. As soon as the young has left the pouch, the mother carries it with her on her back.

We did not think it worth while to shoot the sleeping animal, but sent a little boy up in the tree to bring it down. He hit the bear on the head with a club and pushed it so that it fell, taking care not to be scratched by its claws, which are long and powerful.

The Australian bear is found in considerable numbers throughout the eastern part of the continent, even within the tropical circle. I discovered a new kind of tape-worm which, strange to say, is found in this leaf-feeding animal.

One day our dog put up a kangaroo-rat, which fled to a hollow tree lying on the ground. When we examined the tree it was found to contain another animal also, namely an opossum (Trichosurus vulpecula). It is one of the most common mammals in Australia, and is of great service to the natives, its flesh being eaten and its skin used for clothes. The civilised world, too, has begun to appreciate the value of this kind of fur, which is now exported in large quantities to London. The natives kill the animal in the daytime by dragging it out from the hollow trees where it usually resides. Among the colonists the younger generation are very zealous opossum hunters. They hunt them for sport, going out by moonlight and watching the animal as it goes among the trees to seek its food.

I was now about to leave the capital of Victoria, a city which cannot fail to be admired by the stranger. It is indeed a remarkable fact that in the same place where fifty years ago the shriek of the parrot blended with the noise of the camp of the native Australian, an international exhibition should be held in a metropolis. The first house was built in Melbourne in 1835 - the "World's Fair" took place in 1880. It is not merely in jest that Melbourne is called "the Queen of the South."